In recent years, there has been a global revival: Sherry has emerged from your grandmother’s cabinet and found its way onto backbars and trendy wine lists.

November 6 to 12, 2017 marks the fourth annual International Sherry Week. This year, more than 1,500 events in 25 countries are part of the celebrations, meaning there will be legions of people swilling this historic fortified beverage; sales of Sherry are expected to increase as much 500 per cent during the festivities.

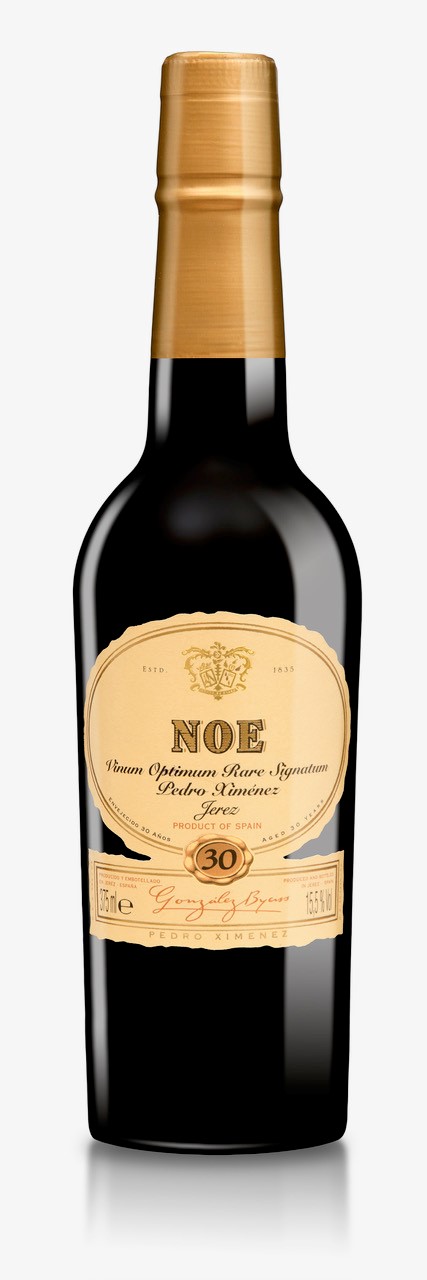

A large part of the drink’s renaissance can be attributed to Gonzalez Byass, one of Sherry’s most renowned producers. Founded in 1835, the family-owned establishment has taken significant strides in the past decade to encourage a new generation to drink Sherry, wisely engaging an influential group: bartenders. Employing industry leaders, they began reintroducing forgotten Sherry cocktails while simultaneously developing new ones. The result: Sherry is back in vogue, mixed and straight up.

But what exactly is it? With a significant decline in popularity in the mid-20th century, much of the general population’s understanding of this globally honoured beverage has fizzled.

To refresh, Sherry carries the name of its geographical location (Jerez-Xérès-Sherry), which is situated along the Atlantic Ocean in Southern Spain’s Andalucía. Grapes have been grown there for millennia, but production has ebbed and flowed depending on who was wielding power. For example, under Islamic law, there was prohibition from 711 to 1264 AD; but then in the 12th century, the British began gulping it with enthusiasm. Its popularity sustained for centuries.

According to Gonzalez Byass chief winemaker Antonío Flores, fortification is only one part of Sherry’s charm. Foremost, the grapes used for its production (palomino, pedro ximènez, and moscatal) are unique, as are the chalky and sponge-like albariza soils the vines are grown in.

Next is the puzzle of making Sherry. It begins as any other wine does, with the pressing of grapes into juice and subsequent fermentation. Dry Sherry is fermented completely dry, then fortified with neutral wine alcohol to 15 per cent. These dry (Fino) Sherries are then moved to wooden casks, leaving enough room inside each to allow for special yeasts called flor to grow on the surface of the wine. Flor is thick and creamy and prevents oxidization of the wine—a process called biological aging.

Fuller-bodied Sherries such as Oloroso are fortified with alcohol to 18 per cent, a level too high for flor to form: ergo, oxidative aging takes place. In the case of Amontillados, the flor dies off (on its own or by winemaker selection), also leading to oxidative aging.

At Gonzalez Byass, sweet Sherries start with late-harvested pedro ximènez (PX) or moscatal grapes, which are left to dry and intensify in the sun. These wines are partially fermented to maintain sweetness, and after fortification are placed in casks.

The more confusing bit is the solera system, which all Sherry is aged in. Solera simplified means each year a portion of wine from a cask is taken to bottle. That cask is topped up with wine from the cask above it, which is one vintage younger, and so on. This graduated aging process can go on for decades, resulting in exclusive casks that can be deliciously old.

Each style of Sherry has a purpose; each drinker has a favourite. Bone-dry Finos are briny and crisp—perfect for salted almonds, sardines, and olives (perhaps at Gastown’s The Sardine Can, where Gonzales Byass and Andrew Peller Import Agency recently held a Sherry Week party). The weightier Amontillado and Oloroso lean toward lacquered wood, dried fruit, and nutty notes; they partner with white meats or artichokes. Sweet PX or cream Sherries are best suited to desserts—or can be poured as a nectarous finale all on their own.

Read more in Food and Drink.