This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus School of Design. Begun in Weimar, Germany by architect Walter Gropius, it was shut down just 14 years later when the Nazis came to power. Favouring functionality over aesthetics, Bauhaus sidelined ornamental flourishes in preference of utility and geometric lines. It is now synonymous with Modernism and the mantras: “Form follows function” and “Less is more.”

Sans serif fonts; wall clocks; Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chair; IKEA (and pre-fab in general): all products of, or imbued with, Bauhaus ideals.

Gropius expected that the Bauhaus (literally German for “building house”) would combine artists and craftsmen under one roof, working together and learning from each other to imagine new uses for, and new ways of, looking at time-honoured materials. Like anything revolutionary, it was a reaction: Gropius had just returned from serving in the First World War and knew the world was marching into a machine age. He was interested in how art, architecture, and design could join it, while still maintaining humanistic ideals.

Some of the 20th Century’s great names of art and design including László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Josef Albers, and van der Rohe joined the Bauhaus faculty. And Gropius’ vision of this new guild of craftsmen was one without elitist hierarchies among the disciplines, although such egalitarianism did not extend to women, who were typically relegated to the weaving department. Still, Anni Albers (wife of Josef) became one of the most important figures of the movement, with her innovative ideas that established ways that textiles could be made integral to architectural design.

Despite the success of a Bauhaus exhibit in 1923, in which the first house built on its principles was showcased to the world, the Bauhaus’ days in Weimar were numbered. The city was conservative, and the radical ideas of the Bauhaus did not sit well with them and, in 1925, they essentially ran the Bauhaus out of town.

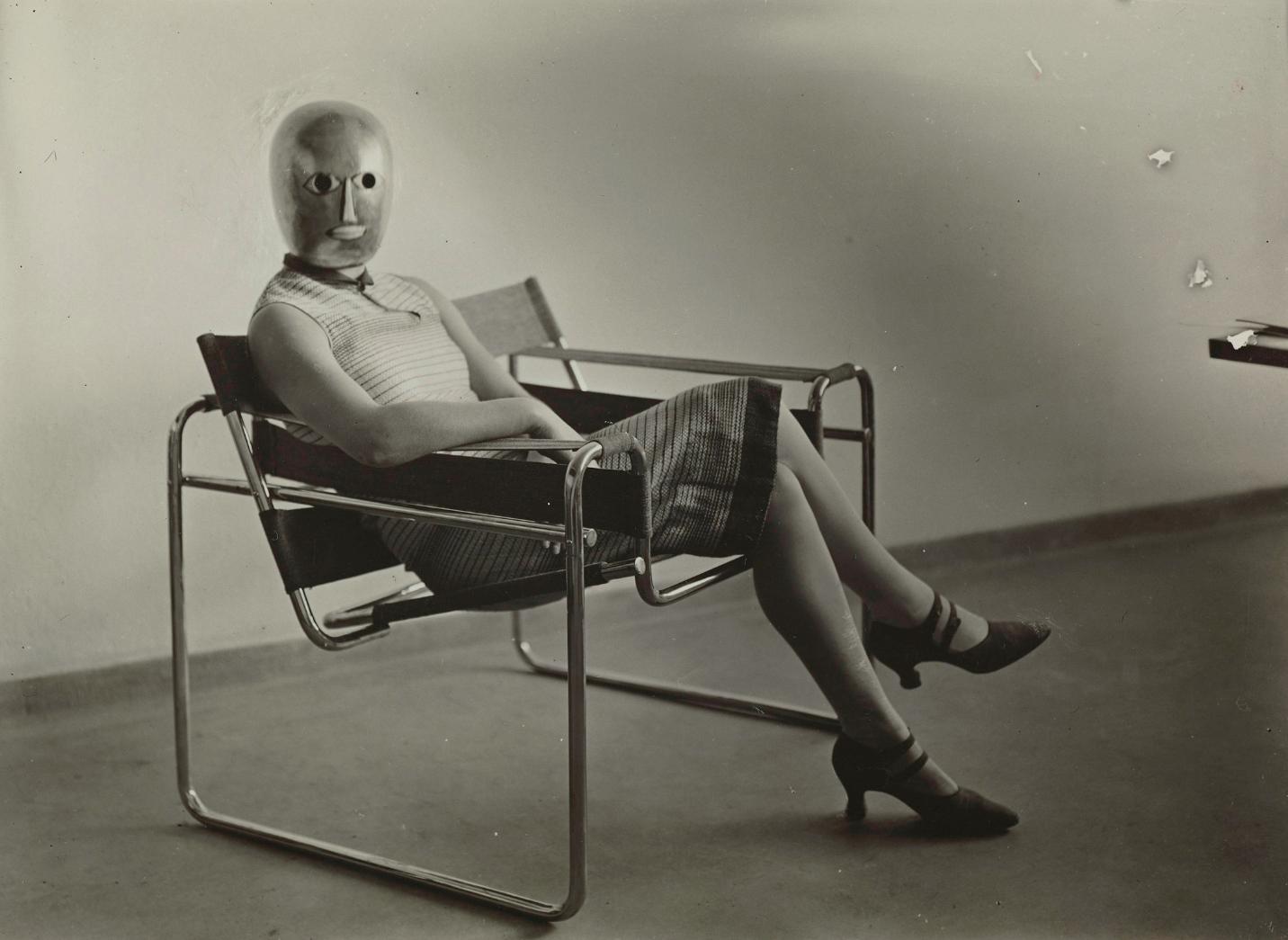

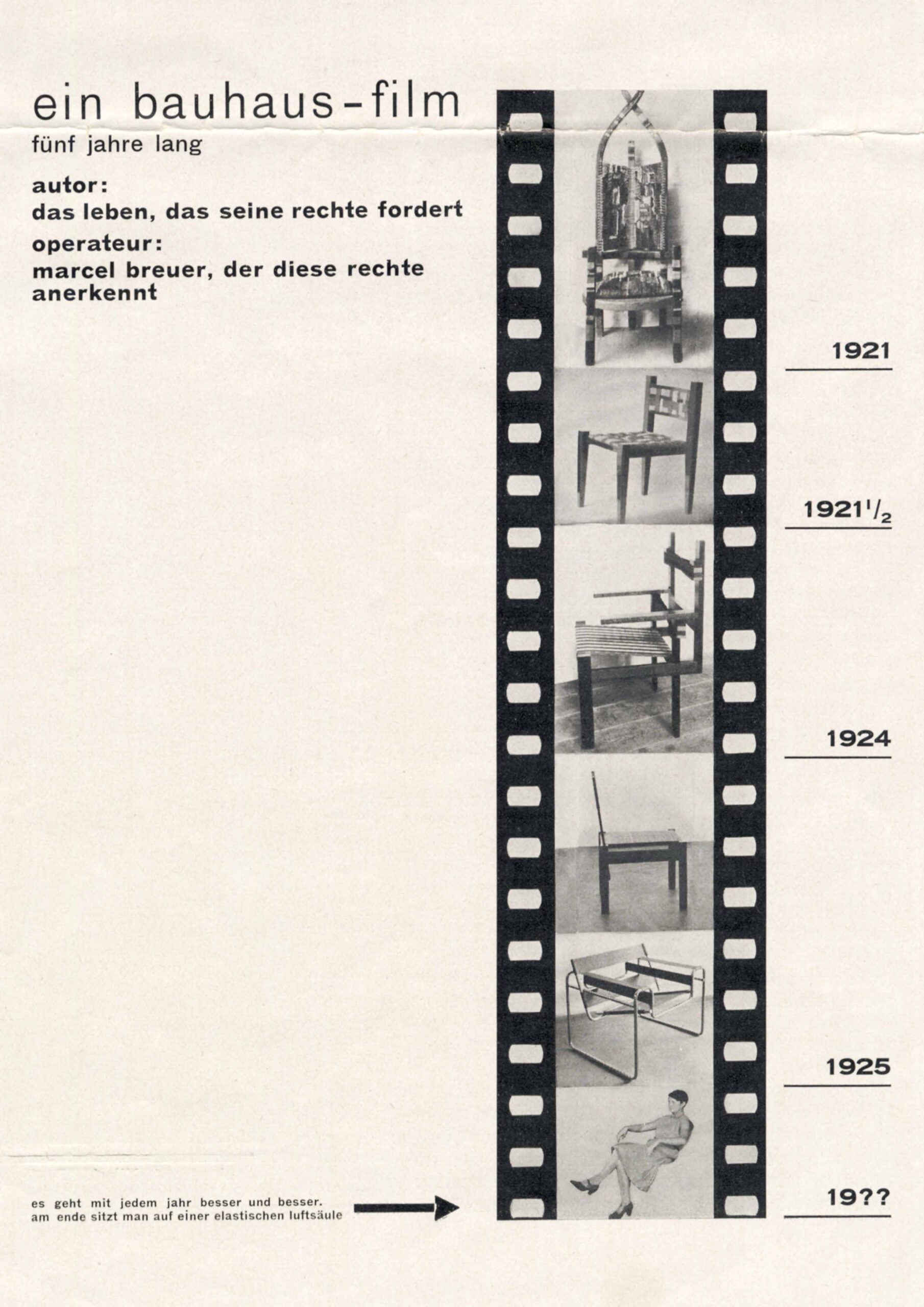

But it was welcomed and funded in Dessau, a small and booming industrial city east of Weimar. The move also marked a change in thinking: it became a unity of art and technique, rather than art and craft. The school began to focus on industrial production of everyday objects, with many of the movement’s best-known products and buildings emerging during this period, including, Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel chair, Marianne Brandt’s ashtray and Kandem lamps, Josef Albers’ nesting tables, and the Walter Gropius cylindrical grip door knob. All are still manufactured today.

In Dessau, Gropius would build his enduring Bauhaus legacy and one of the iconic buildings of the 20th Century: the Bauhaus Building, which opened in 1926 and now has UNESCO Heritage status. Stripped to elemental lines and planes, it featured a glass facade that gave an inside/outside aesthetic. Today such an angular, minimalist building is standard for modern design but at the time, a rectangular glass building on the rolling hills of a small German town, was a sensation.

The school moved to Berlin in 1932 where, under the directorship of van der Rohe, it became almost exclusively focused on architecture, but was given no time to flourish: the Nazis—who considered the Bauhaus school degenerate— shut it down soon after.

Many members of the school moved to the United States. Gropius took over Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, where Marcel Breuer joined him. Maholy Nagy set up a new Bauhaus in Chicago, while van der Rohe would go on to build the iconic Seagram Building in New York. In the U.S., the Bauhaus movement became known for objects, and less for its radical (socialist) ideals.

By the middle of the century Bauhaus became the go-to Modernist style around the world, its influence evident in places as diverse as Guatemala City, Congo, Shanghai, and the former Yugoslavia.

But the Bauhaus legacy is perhaps most strongly seen in Tel Aviv, the place where a number students and disciples moved, fleeing Nazi persecution. A prevalence of white, clean-cut housing, with roofs to socialize on, soon dominated the city. The “White City”—the Bauhaus-dominated central area of Tel Aviv—is another UNESCO heritage site.

All the major stops on what could be called the “Bauhaus Grand Tour” are celebrating its centennial with events and open houses. New Bauhaus museums are opening in Weimar and Dessau this year, and in Berlin, the Bauhaus Archiv museum (which holds an in-depth collection of Bauhaus objects) will hold a year of events dedicated to the school. In Tel Aviv the Bauhaus is being feted with an ongoing series of lectures and walking tours at the Bauhaus Center. And German photographer Jean Molitor explores the global reach of Bauhaus in a sumptuous new photo book, Bauhaus—Modernism Around the Globe.

View more from Design.