Author Aaron Chapman has Tommy Chong to thank for one of the most nefarious highlights in his new book, aptly titled Vancouver After Dark: The Wild History of a City’s Nightlife.

Though Chong may be best known as half of the pioneering stoner comedy duo Cheech & Chong, he moved to Vancouver in 1958 to cut his teeth as an R&B guitarist and later tipped Chapman off to a bust-up at Granville Street’s long-forgotten Berolina Cabaret in 1964, where members of the Quebecois criminal underworld tore up the joint as part of their protection racket.

“They burst into the place with chains they were swinging around, and smashed up the bandstand. They were arrested and went to jail,” Chapman says.

This is just one of the many colourful yarns threaded throughout Chapman’s latest local history book, which follows his Liquor, Lust, and the Law on the Penthouse Nightclub, and Live at the Commodore, an in-depth look at the celebrated ballroom. While both of those venues are still standing, Vancouver After Dark takes a different approach by saluting dozens of since-closed spots, dating all the way back to the opening of “Gassy Jack” Deighton’s Globe Saloon in 1867.

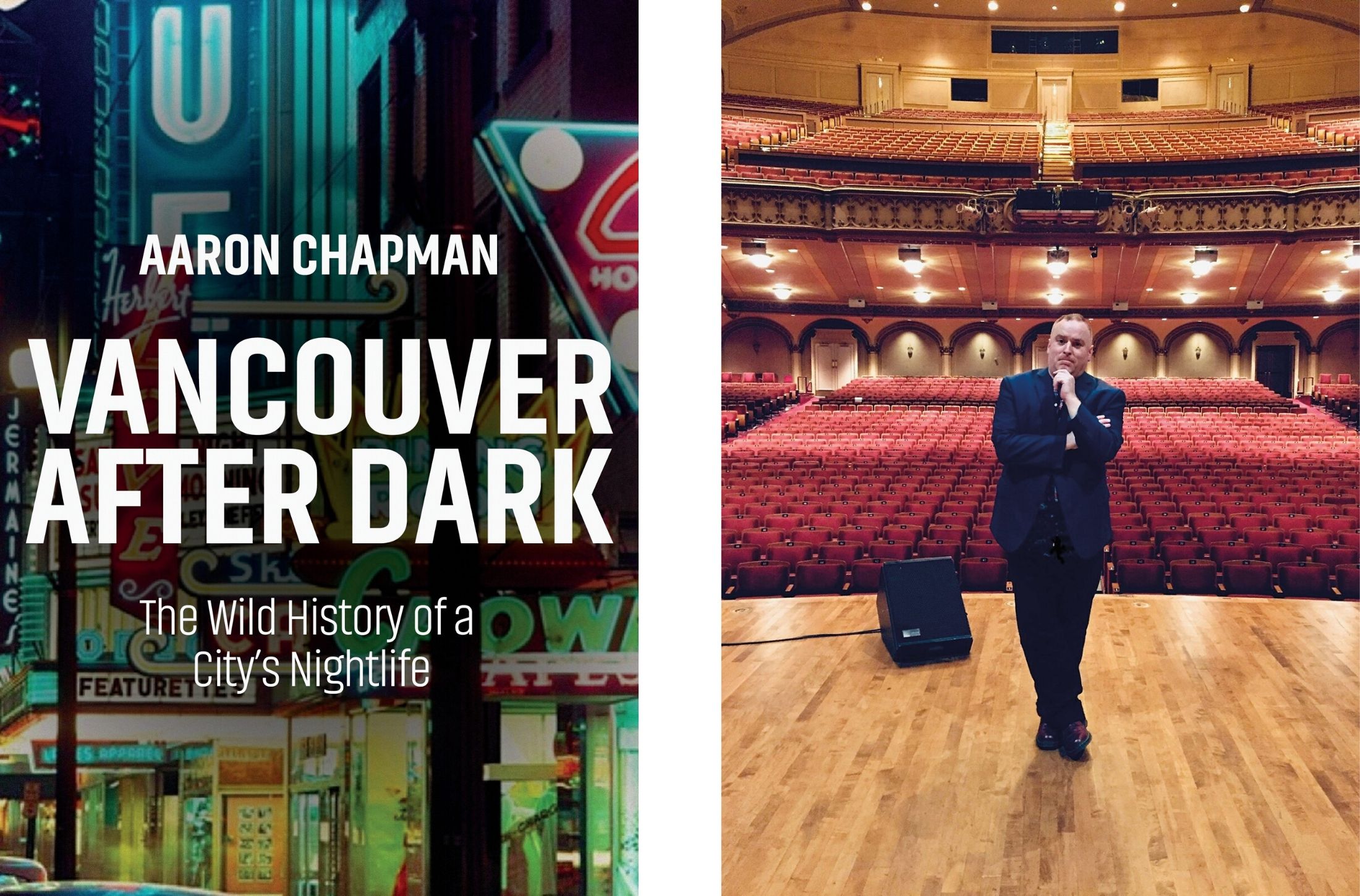

Photo by Mike Derakhshan/Arsenal Pulp Press.

The author pulls from over a century’s worth of lore for Vancouver After Dark, contrasting glamorous performances by Billie Holiday at the Palomar Supper Club with D.O.A. and the Dead Kennedys’ sneering sets at punk dive the Smilin’ Buddha Cabaret.

It also explores seedier stories like the “drum-roll murder,” a 1971 incident at Club Zanzibar where, during a strip performance’s grand finale, an audience member wearing a wig and a fake moustache timed a fatal gunshot to another patron’s head with the onstage crash of drums. The shooter apparently darted out of the club into a 4×4 truck, never to be seen again.

“People always say that Vancouver is such a young city and that we’ve got no history here. I think that’s bullshit. There’s tons of history here! You just have to scratch the surface,” Chapman insists.

“For far too long we’ve been shown the chamber of commerce view of Vancouver history—it talks about the forest industry, or the railway that came here. That’s interesting enough, and there’s something to be learned from that, but I think there’s a lot more to be learned about how Vancouverites met socially, where they interacted in spaces other than boardrooms.”

Chapman has spent the entirety of his adult life immersed in Vancouver nightlife, gigging around town in the early 1990s with Celtic punk band the Real McKenzies, and more recently with the Town Pants. In Vancouver After Dark, he also recalls the musty charm of the beneath street-level Pig and Whistle, and the terrible sound at the Plaza of Nations, an outdoor venue erected for Expo 86 whose rotted-out stage was levelled by the city in 2018 after a decade of inactivity.

One of the city’s most celebrated venues was the Cave, a Hornby Street club that opened its doors in 1938. Fittingly, papier-mâché stalactites lined the venue, but the vibe was divine, not dank. Known as one of the city’s premier nightclubs, it hosted performances from the likes of Lena Horne, Marvin Gaye, the Supremes, and countless other top-shelf entertainers. Chapman notes that many interviewees fondly remember the Cave, which was ultimately bulldozed in 1981.

The Cave menu featuring singer Lena Horne. Photo courtesy of Neptoon Records Archives.

Local trombonist Ernie King once said the Cave’s management didn’t always extend its inclusivity to people of colour in Vancouver, preferring to employ an all-white house band. King later opened Vancouver’s only Black nightclub, called the Harlem Nocturne, in 1958. Though a popular spot, the club was repeatedly denied a liquor license and faced countless city crackdowns. In 1969, after a decade of hassles, King shut down his club.

A recurring theme of Vancouver After Dark is how venues often changed hands, yielding dramatic clientele shifts in the process. Chapman notes, for instance, that a country-western bar from the 1970s called the Purple Steer would later transform into dance music hub Luv-a-Fair in the 1980s (it was leveled for condos in 2003).

Isy’s Supper Club, initially a Las Vegas-style showroom, was banned from hosting a comedy performance from Lenny Bruce in 1962 over presumed indecency; it remodeled itself a decade later as Isy’s Strip City to compete with topless wrestling at Club Zanzibar. By the mid-1980s it was running as the heavy metal-friendly Metro, which brought in New Jersey rockers Bon Jovi as customers when they were recording Slippery When Wet in town. On the fringes of Gastown, the building that used to be the Brickyard—an enclave for garage rock bands around the turn of the 21st century—is now subdivided into a coffee shop and a vintage clothing store.

Vancouver After Dark is a passionately detailed exploration of the city’s forgotten night clubs, but Chapman’s latest shouldn’t be read as an elegy. Rather, it’s a link to the city’s ever-evolving landscape. “No city is a museum,” Chapman says. “They’re supposed to change.”

Whether it was Cave dwellers in the ’60s or Gen X grunge fans seeing Pearl Jam at the Town Pump in 1991, many After Dark interviewees hinted that the party is over for Vancouver. All the good clubs, they say, are gone. Chapman’s not convinced. The venues may have changed, but the spirit of Vancouver nightlife lives on.

Art Bergmann on stage at the Town Pump. Photo by Kevin Statham/Arsenal Pulp Press.

“That’s a funny thing about glory days, they transfer with each generation,” he says. “I guarantee you there’s some kid that went out last night, and when he’s 42 he’s going to talk about [how this] was the greatest time to be in Vancouver.”

Aaron Chapman and Arsenal Pulp Press are hosting a book launch for Vancouver After Dark on November 28 at 7pm at Central Studios (formerly the Hollywood North, formerly the Playpen Central, formerly the Thunderbird Club) at 856 Seymour Street in Vancouver.

Discover more local history.