For 20 years, the boxes sat unopened in the home of Dr. Michael Hayden, a renowned Vancouver researcher in molecular medicine, human genetics and Huntington disease. For decades prior to that, they had remained similarly unopened—and unmentioned—in the South African home of Hayden’s father.

“One night, I finally felt I could confront it,” he says. Opening the boxes, he discovered family history dating back to the 1850s and leading up to 1941. There were 9,000 original documents, including letters between Hayden’s grandparents and his father, who had been sent as a boy from Germany to London for safety at the start of the Second World War.

“The letters tell incredible stories of heartbreak,” Hayden says.

There were also photographs, prints by famous artists, autographs of Mark Twain and American presidents, a stamp collection, rare maps, small Jewish ritual objects and much more, including Nazi edicts relating to the incarceration of Max Raphael Hahn, Hayden’s grandfather.

Gertrud and Max Hahn, seen here in Berlin in 1918, were successful entrepreneurs and property owners in Germany before they were killed in the Holocaust. Courtesy of the Hahn family.

These items represent the last tangible legacy of Gertrud and Max Hahn who, as it turns out, had one of the most significant private collections of Jewish art in Europe at the time, rivalling those of the Rothschild and Sassoon families.

Until the Nazis stole it.

Max was arrested on Kristallnacht—“the night of broken glass”—which occurred 81 years ago on the night of Nov. 9-10, 1938. That date represents the transition from the Nazis’ creeping discrimination against Jewish people to the beginning of the violent cataclysm that would culminate in the Holocaust.

On that single night, Jewish homes, schools, businesses and institutions were attacked across Germany and Austria, 267 synagogues were destroyed, nearly 100 Jews were murdered and 30,000 Jewish men, including Hahn, were arrested. Later, Gertrud, too, would be seized and the couple transferred to Riga, Latvia, where they were murdered by Latvian collaborators of the Nazis.

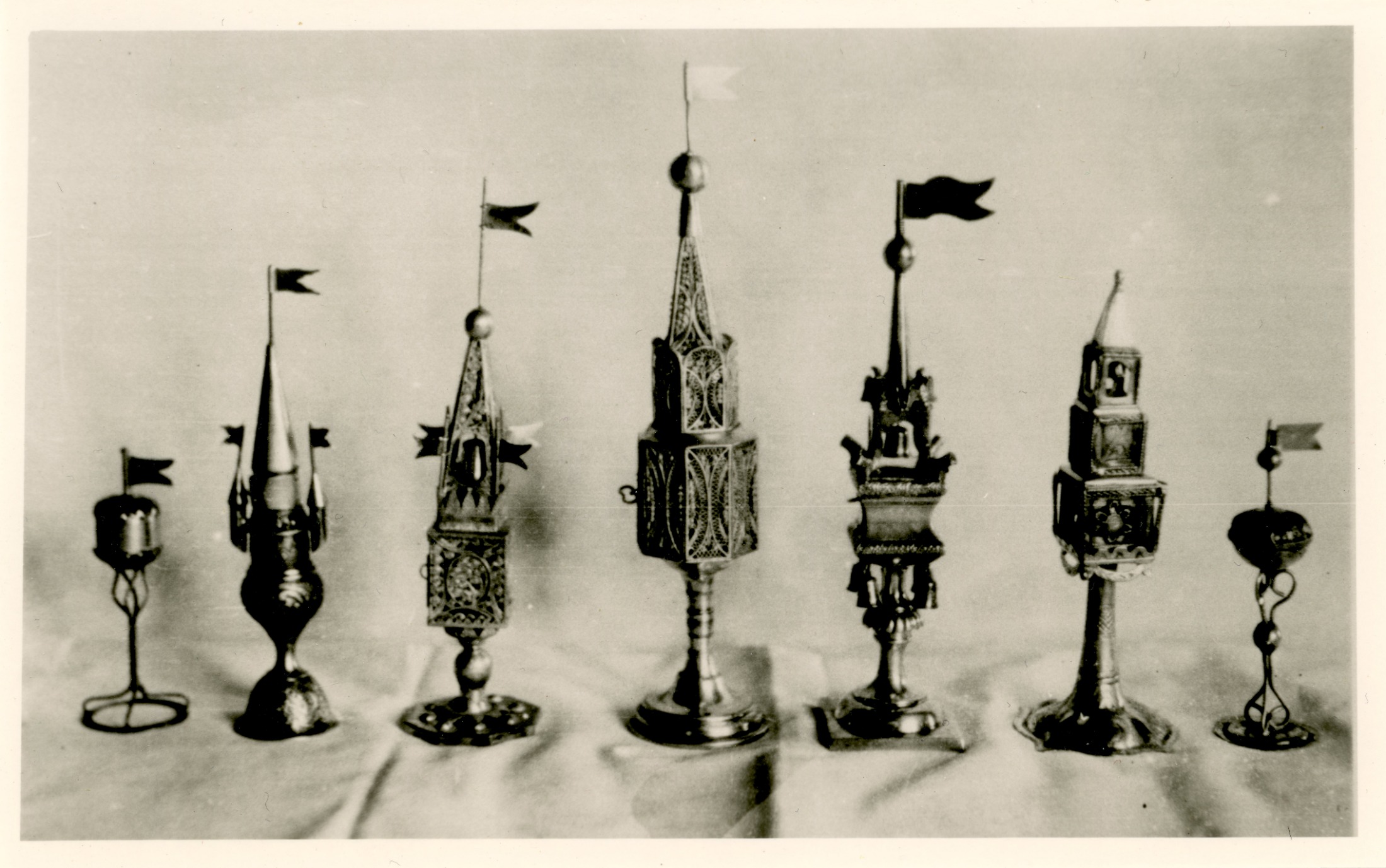

Spice boxes, also known as besamim boxes, were the heart of Max Hahn’s silver Judaica collection. Of the original 65 pieces, only six were saved from the Nazis. Courtesy of the Hahn family.

An exhibition, “Treasured Belongings: The Hahn Family & the Search for a Stolen Legacy,” opened Nov. 7 at the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. As impressive and fascinating as the exhibition and the artifacts themselves are, the narrative of how the items were secreted out of Germany to Switzerland and Sweden—where they were recovered after the war by Hayden and his sister—tells a story of intergenerational loss and restitution.

Because the Nazis had required Jews to declare—and then surrender—all silver, the Hahns had created an inventory of their substantial trove of silver religious items, including many photos. This has been crucial because, while the German government and German museums have been proactive in advancing restitution efforts, Hayden says descendants are often stymied by their inability to prove ownership.

This silver gilt Kiddush cup from the 1700s shows the biblical story of Jacob. Courtesy of Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.

One incomparable artifact in the exhibit is a silver Kiddush cup from the mid-1700s, used as a ritual item for wine used during Sabbath, that depicts the biblical story of Jacob’s vision of a ladder to heaven. The cup was discovered in a museum in Hamburg and was recently restituted to the Hayden family. Other items have been located in German museums and the family has, for now, left them there, effectively on loan.

Restitution, Hayden says, is important not because of any material value but because of the personal significance and because it represents “some steps toward reconciliation and restoring dignity.”

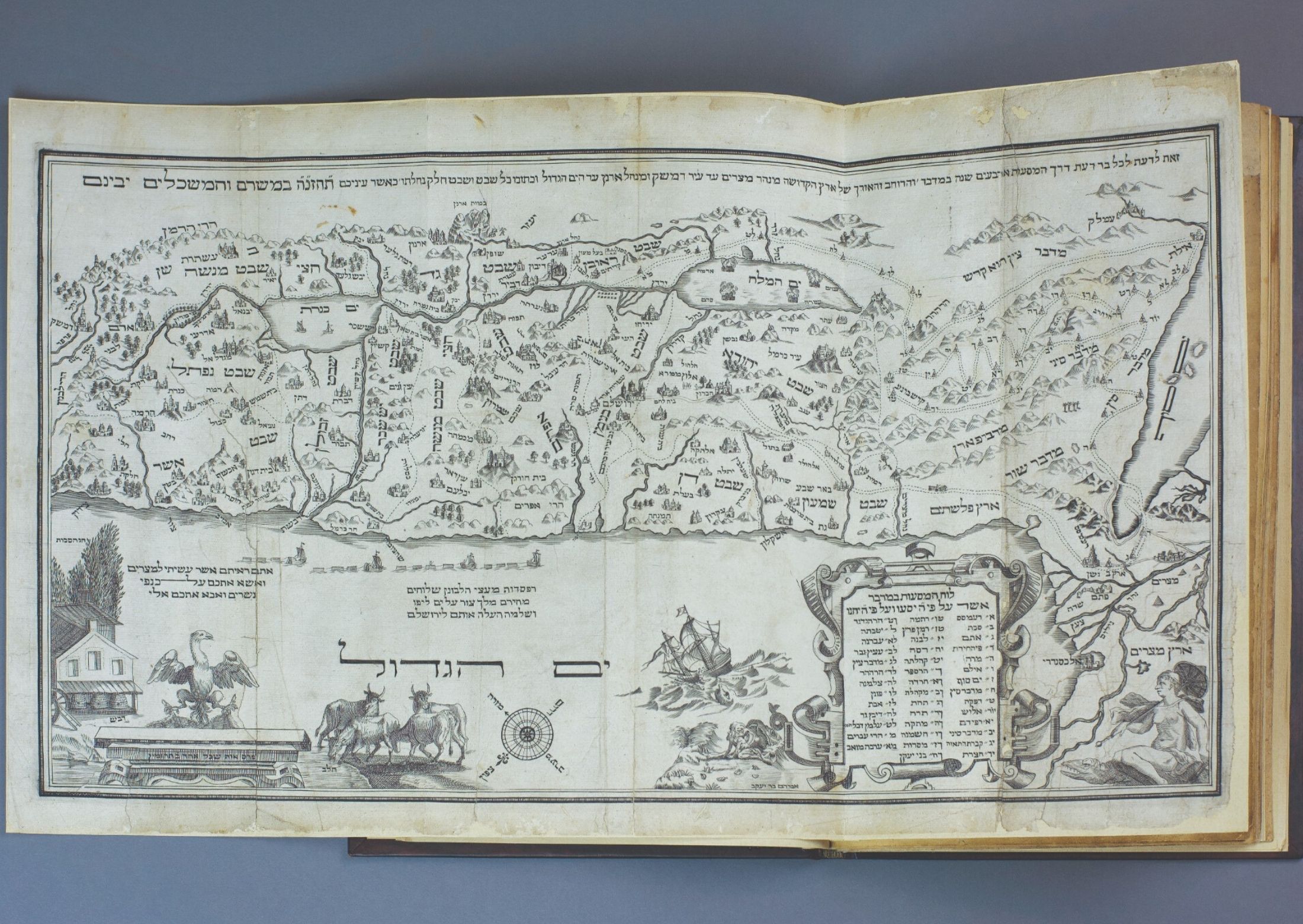

Max Hahn’s extensive Judaica collection included this 1695 Haggadah, believed to be the first Hebrew book to include a map of the Holy Land. Courtesy of Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.

Immersing himself and visitors to the exhibition in this dark history is an important way to respect the victims, but it has direct implications for today as well, Hayden says.

“It’s been an opportunity to give individuality and identity for two of six million people who were murdered,” he says. “To rescue them from generalizations and understand who they were, and understand their distinctiveness. To bring my grandparents out of obscurity and give them the warmth and respect they deserve.”

On lessons for today’s world, he adds: “We need to be vigilant on many levels. We need to be protecting the rights of immigrants, we need to be vigilant on being aware that history can be repeated, the emergence of the far-right, the antisemitism that’s happening in lots of places… Racism is everywhere.”

The “Treasured Belongings” exhibition continues until November 2020 at the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.