Deluge myths have been told in nearly every part of the world for thousands of years. The Ancient Greeks have the flood of Ogyges; there is the Gun-Yu Great Flood in China; the Māori of New Zealand tell the legend of Ruatapu’s flood.

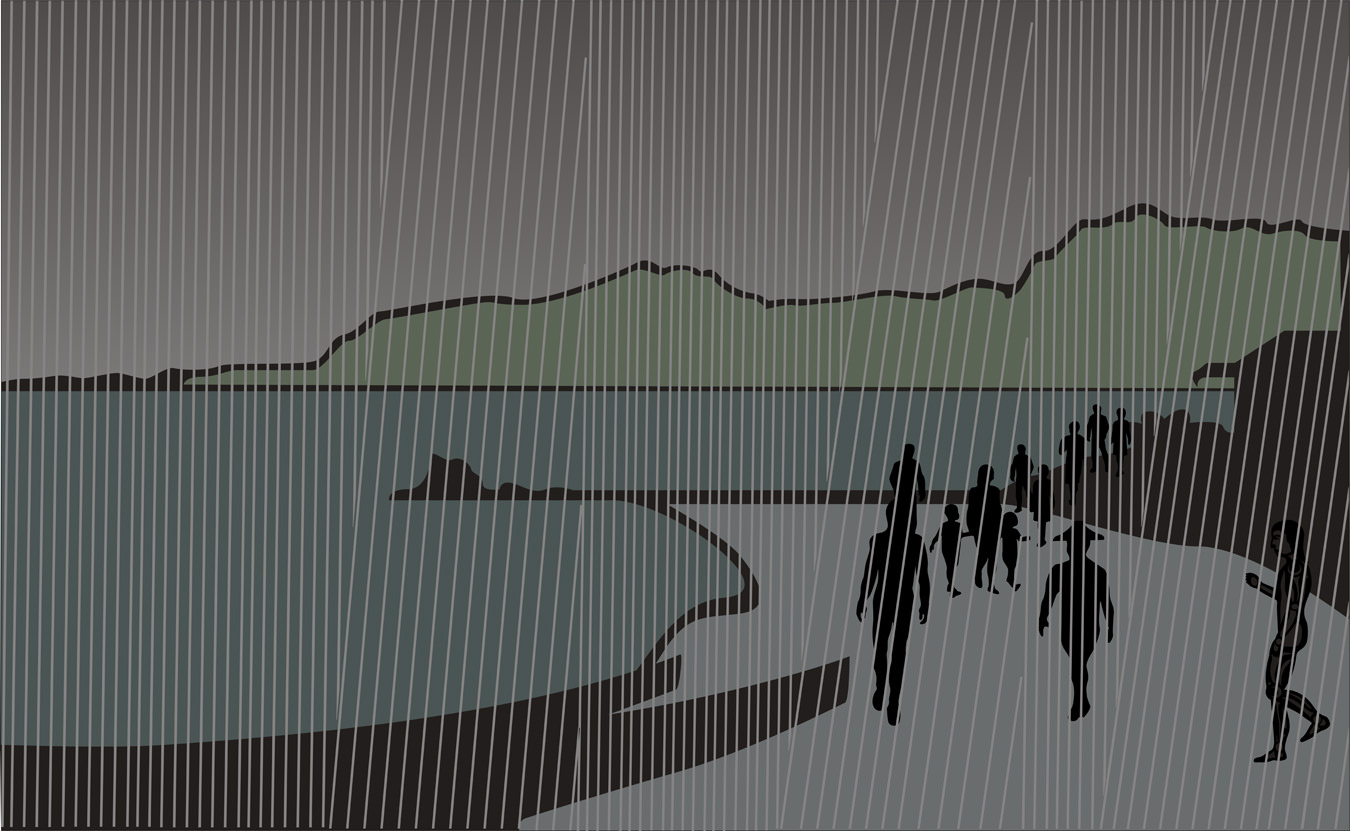

Peace Dancer is another one of those tales. The fourth book illustrated and co-written by artist Roy Henry Vickers, as part of his Northwest Coast Legends series, tells the story of a generation of Kitkatla children that has lost the ways of the elders. Their disrespect to the land, to tradition, causes the earth to retaliate with a great flood, not to be set right again until they have learned respect for nature and how to give thanks. It’s a story that Vickers has told many times before in words, and through his art.

Born in the small Northern British Columbia town of Greenville to a First Nations father and a British mother, Vickers’s art fuses the traditional pictorial elements and narratives of the Northwest Coast people with his own unique perspective. His work is immediately recognizable by its flat planes, black cut outs, and intense vibrancy (due to his partial colour blindness). But it’s the stories told in Vickers’s work that are most discernable, each piece used as a means to convey something larger. “We’re all artists; every human being is an artist,” Vickers says joyfully, when asked why he became an artist. “For me, I came across discrimination in the city in Victoria and it piqued my curiosity: ‘What do they see, what do they think?’ And when I found out what they saw and what they thought, I thought, ‘How ignorant. And I know better than them about First Nations peoples, so I’m going to show them.’”

Along with Bill Reid and Robert Davidson, Vickers is recognized as one of the most prolific artists of the Northwest Coast. His work can be found in museums and private collections around the world, as well as at his own Eagle Aerie Gallery in Tofino. He also holds a long list of honours, including the Order of British Columbia and the Order of Canada. Additionally, Vickers is a recipient of a Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal—in fact, he has dined with Her Highness twice. “It was humbling, still is,” Vickers says, tears welling in his eyes. “I had long before that [second dinner] dealt with the anger and resentment of colonization, and the problems of being discriminated against because of the colour of my skin. Ten years earlier I was invited to dinner with Queen Elizabeth at her Silver Jubilee at the parliament buildings, and at that time I was a young, ignorant, angry, self-centred artist, and I felt like I was a token Indian. But 10 years later, none of that was there.”

Vickers continues to be a champion for the First Nations people, serving as a pipe carrier and sweat lodge leader, and also fighting for the rights of his community in Canada. But perhaps his most important role is telling his people’s stories—his stories. “I always used to say, ‘I’m not political,’ but it was more a combination of being First Nations but also being half English, struggling with the fact that I’m not a traditional Tsimshian, I’m actually Tsimshian and Haida and Heiltsuk,” he explains. “So how can I be a Tsimshian artist when I’m also a Haida and Heiltsuk? How do I put this all together? And to me those aren’t rhetorical questions, they’re questions that I want answers to. And I found the answers, and that’s what I do today.”

More from our Arts section.