Upon entering the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art in downtown Vancouver, visitors are immediately greeted by Sea-Wolf. The supernatural Haida creature sits at the foot of the Celebration of Bill Reid Pole, carved by Haida master carver and hereditary chief James Hart (Chief 7idansuu). At the top of the pole is Raven, with an image of the late Bill Reid carved into his chest, watching over the gallery and its happenings.

Reid, who was raised by a Haida mother and American father in Victoria, remains one of the most well-known names in Indigenous Canadian art. His Haida heritage helped define his diverse artistic career, which spanned sculpture, carving, printmaking, gold and silver jewellery-making, and writing. Perhaps his most famous piece is The Raven and the First Men—a large, stunning sculpture that sits inside the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology. The raven plays an important part in Reid’s work; he was a member of the Raven clan from T’aanuu, and in 1986 was given the Haida name Yaahl Sgwansung, or The Only Raven.

Opened in 2008, the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art honours Reid’s incredible contributions to First Nations culture (and Canada’s awareness of it). As the country’s only public gallery dedicated to the Indigenous art of this region, it is anchored by its permanent Reid collection, though it also hosts rotating exhibitions that showcase emerging artists. And just in time for its 10-year anniversary, the gallery debuted a $1.8-million facelift in June 2018; the renovations transform the mezzanine level into additional viewing and educational programming areas and add a covered outdoor terrace for receptions and live carvings by local artists. The gallery is committed to regular exhibitions, school programs, artist talks, and film presentations, and the new spaces will further promote conversations about contemporary Indigenous culture and art. To celebrate the diversity of Indigenous voices, gallery curator Beth Carter plans on working with a guest curator for each new exhibition.

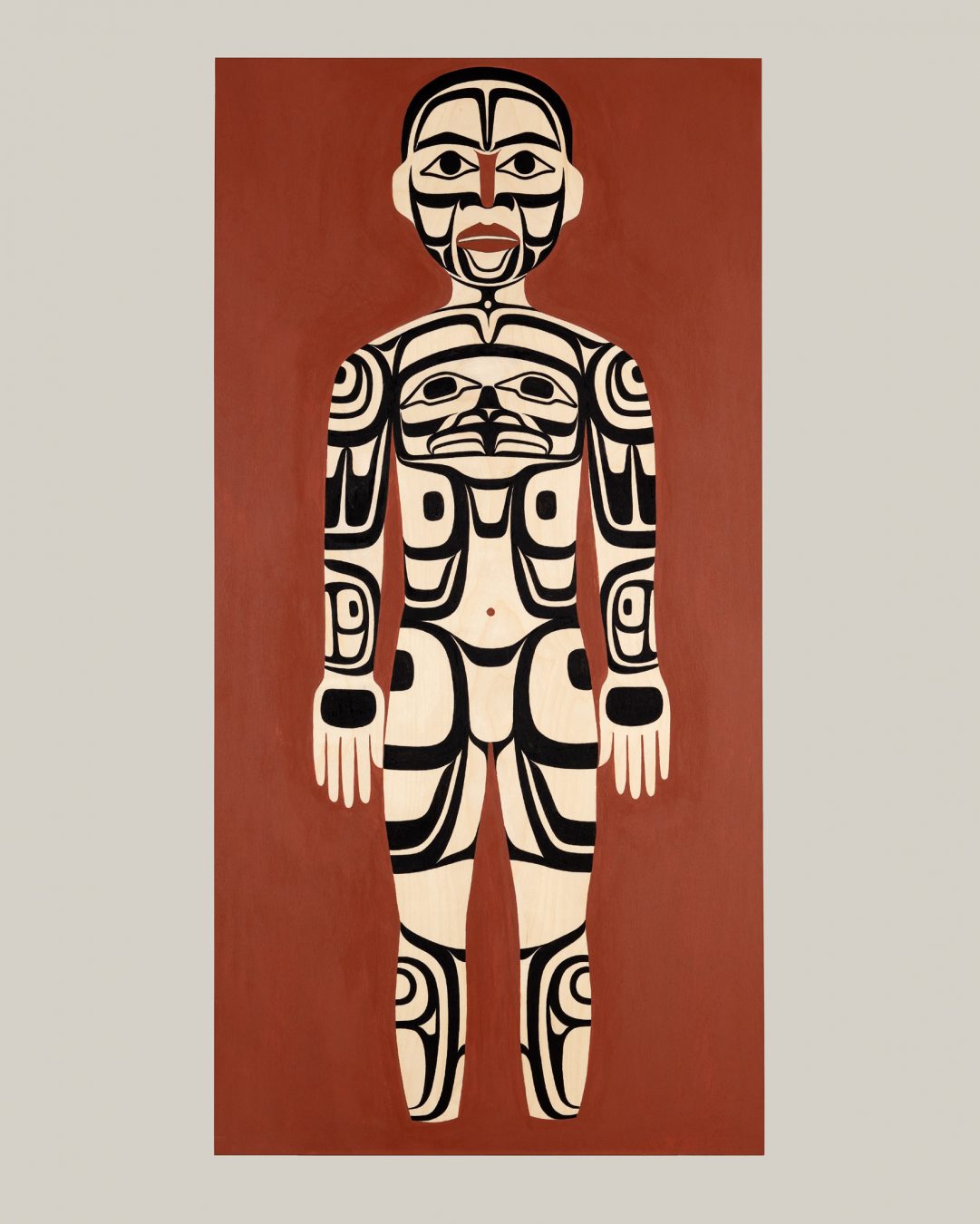

Its debut show post-revamp, “Body Language: Reawakening Cultural Tattooing of the Northwest” (on until Jan. 13, 2019), highlights the work of five cultural tattoo practitioners. It is the first exhibition to explore and highlight Northwest Indigenous tattooing and piercing, and it does so through multiple mediums: a series of photographs showing contemporary works; installations and carvings that illustrate cultural identities and ancient stories; ornamental objects (such as “labret” lip piercings); and video footage of the artists speaking about tattooing traditions.

“The exhibition takes you on a series of connected journeys,” says guest curator and featured artist Dion Kaszas, who is Nlaka’pamux, Hungarian, and Métis. Prior to the ban of First Nations potlatches in 1885, tattooing was an integral part of life for the people of the Northwest Coast, representing and marking major events, status, and identity (as well, piercings in the nose, ear, and lip were important rank symbols). The potlatch ban, which was not lifted until 1951, prompted communities to instead put their clan crests and personal designs on clothing and jewellery, which also helped cover existing tattoos.

In present day, cultural tattooing is seeing a resurgence, and the exhibition highlights that, too. “We’re healing our connections to our communities,” says Kaszas. One of the other exhibited artists is Nakkita Trimble; her Nisga’a hand-poked and skin-stitched pieces depict house crests belonging to matrilineal lines. “This practice has been asleep for over a hundred years and we’re reawakening it,” she says. “I’m doing this for my great grandmother, my grandmother, my daughter, and for her children in the future.”

For many Indigenous people today, getting a traditional tattoo is a way to rebuild, rediscover, or reassert Northwest Coast identity. “It’s very humbling when someone who has been tattooed by me stands up and looks at that piece and you can tell they feel more connected,” says Kaszas. “They feel more grounded, more rooted. It’s that sense of being whole.” There is likely nothing that would have made The Only Raven prouder.

Keep making a positive Impact.