Dr. Karim Qayumi has a knowledge surpassing encyclopedic about his native Afghanistan, from where he emigrated to Canada in 1983. And he still returns there, regularly in his professional capacity as a physician and surgeon. Here in Canada, he dreamed of bringing certain radical ideas about how surgery is taught, and learned. That dream, once branded as idealistic and too far in the future to be practicable, is actually here, now, at the Centre of Excellence for Surgical Education and Innovation, where Dr. Qayumi is director. Housed at Vancouver General Hospital, the Centre is in fact an adjunct of the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine, at which Dr. Qayumi is also a professor of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery.

He is thoughtful in everything he says and does, and the quiet, simmering determination with which he approaches problems has a lot to do with the remarkable success he has had in his surgical practice and at the Centre. Today, it has become a beacon of advanced learning that draws attention from all over the world. “We set out to do two main things,” he says in his quiet office in the Centre. “First, how to take the learning process for surgeons out of the operating room; how to make learning safer and less costly. After all, surgery is a skill-based thing, requiring repetition and physical training in addition to study. And second, how to incorporate technology, computer-assisted instruction, animation technology.”

Surgeons learn by doing, and it is not too difficult to imagine how that used to be done. Read, assimilate, observe others doing the work, but eventually, as Dr. Qayumi puts it, “You have to actually cut into a human being. There is no way around that. And the first time one does that, there is some sort of risk attached. Like everything else in life, you get better at it the more you do it. So, for medical surgery, the process of bringing a doctor to the point where they are ready to actually perform surgery on a patient is lengthy, and of course extremely costly.” Dr. Qayumi came at this problem with constructive theories of learning as defined by Piaget, along with some cognitive and behavioural theory, and eventually came to a system in which doctors could practise in an environment that taught them skills, through both positive and negative reinforcement, but not on live patients. Instead, Dr. Qayumi says as he smiles, “You can just turn on the computer and go to the ward, and do the work on your cyber patient.” The computer program will track every detail, including where things went well and if and where they went wrong.

“The whole model in medical education was ‘see, do, teach’. A kind of apprenticeship program. But this is not enough.”

The idea came from the aviation industry, where pilots, in whose hands many thousands of people are held each year, are thoroughly trained on flight simulators before they ever actually have the controls up in the air. “Instead of airplanes, our doctors work on a gall bladder, a damaged knee, hip replacement, open-heart surgery, neurosurgery. We can simulate anything.” The program can also be designed to create scenarios in which something unexpected occurs—say an allergic reaction to medication, or an unpredicted stroke while in surgery—and the reactions of the entire team are monitored. This way, the real-life contingencies of surgical procedures are encountered by a physician before any actual surgery on a live patient. “The whole model in medical education was ‘see, do, teach’. A kind of apprenticeship program,” says Dr. Qayumi. “But this is not enough. To prevent disaster in the ‘do’ stage was an extremely long and costly process. Now, here at the Centre, the ‘see’ phase is intact, but the ‘do’ phase means someone can perform 100 virtual procedures before doing anything on a live patient.” Part of the Centre’s mandate, understandably, is constant analysis of performance and, as Dr. Qayumi states, “The results are outstanding.” The world seems to agree.

A team from Karachi is doing an in-depth tour of the facility, joining the ranks of teams from Saudi Arabia, Europe, Asia and the United States. The Centre of Excellence is the first of its kind to be accredited by the American College of Surgeons, so the ripple effect from the Centre at VGH is brisk and deep. There is now an entity called the Canadian Network for Simulation in Healthcare. “We provide services to a lot of medical agencies outside of the University,” Dr. Qayumi acknowledges. It is a long way from the early nineties, when his ideas were considered radical, impractical, impossible to execute. But the results have been resoundingly positive. A mortality rate hovering around two per cent for surgical procedures, due to error, is rapidly becoming a thing of the past.

“Yes, touch. We will soon be able to palpate a tumour, for example. It will again change the whole course of surgical procedures.”

The team at the Centre is 46 strong, all University of British Columbia faculty. Dr. Qayumi speaks of them as “A whole team, outstanding, without whom I would be just another person standing on the side of the road.” A fascinating analogy, since he has witnessed many talented people being left behind, or cast aside, in parts of the world where the privilege of research and scientific excellence are not even possible.

The future is nigh: “Haptics are pretty much here. I would say a year, perhaps two at the most. And that will be yet another breakthrough.” Haptics: a technology in which not only visual realities are available, but the sense of touch as well. Touch? “Yes, touch. We will soon be able to palpate a tumour, for example. It will again change the whole course of surgical procedures. The reality of each procedure will be experienced by surgeons many, many times before they actually perform that specific procedure on a patient. It is a marvel. We know what we are looking for. And the research we do is vital.” It reduces what Dr. Qayumi terms the “time of threshold” for doctors to become surgeons, plying their skills on real patients. A comforting thought.

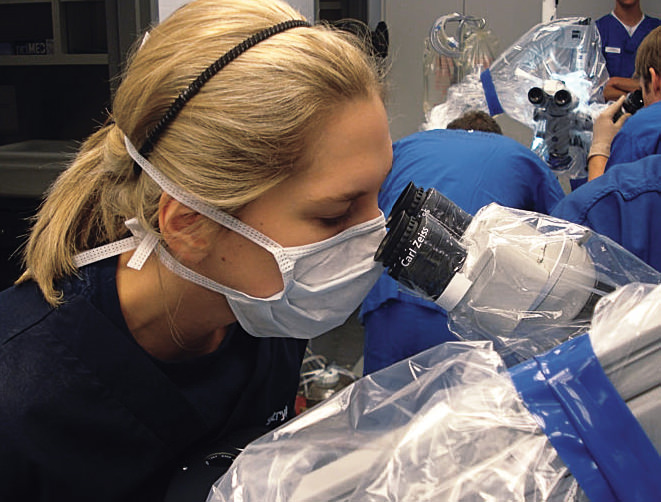

Technology evolves, and the Centre keeps abreast of it all, and in fact motivates some of it. To walk a few paces within the Centre is to witness a silent progression; these are not students, but seasoned practitioners of the knife, surgeons in the making who will not have the sense of trepidation and excitement their predecessors had. Instead, there will be a seasoned hand, a practised touch, as they move in to remove your appendix, stitch your lip, put a shunt in your brain, repair the faulty aorta. It is not Star Trek, exactly. It is reality, thanks in no small part to Dr. Karim Qayumi and his team.

Photos: Cesei.