The romantic notion of the sublime is perhaps most clearly articulated in David Casper Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. Cast above endless terrain, a single man surveys the unimaginably vast expanse of nature. Terrifying in its beauty, this world is wholly too large, unable to be captured by the feeble human hand.

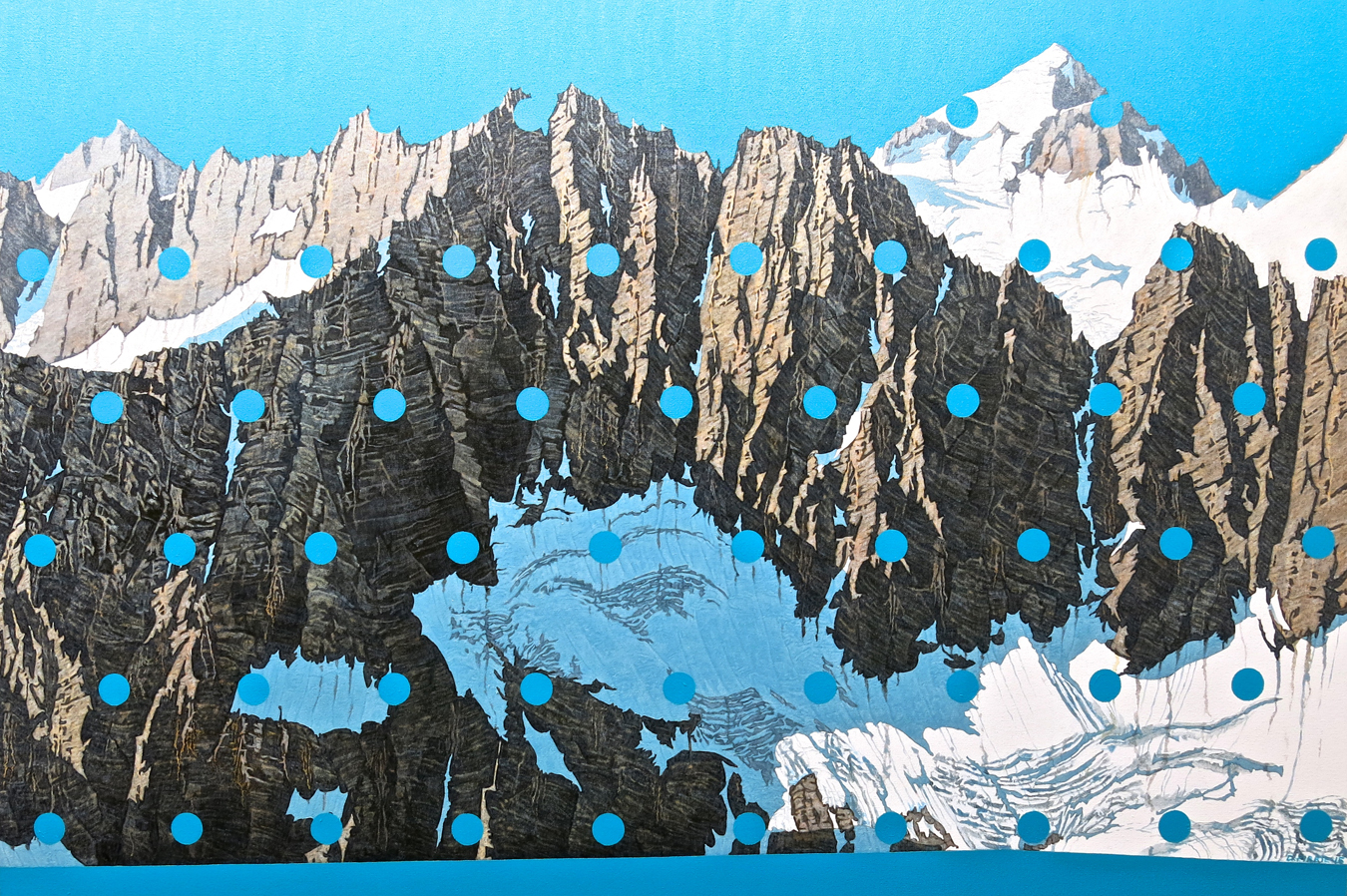

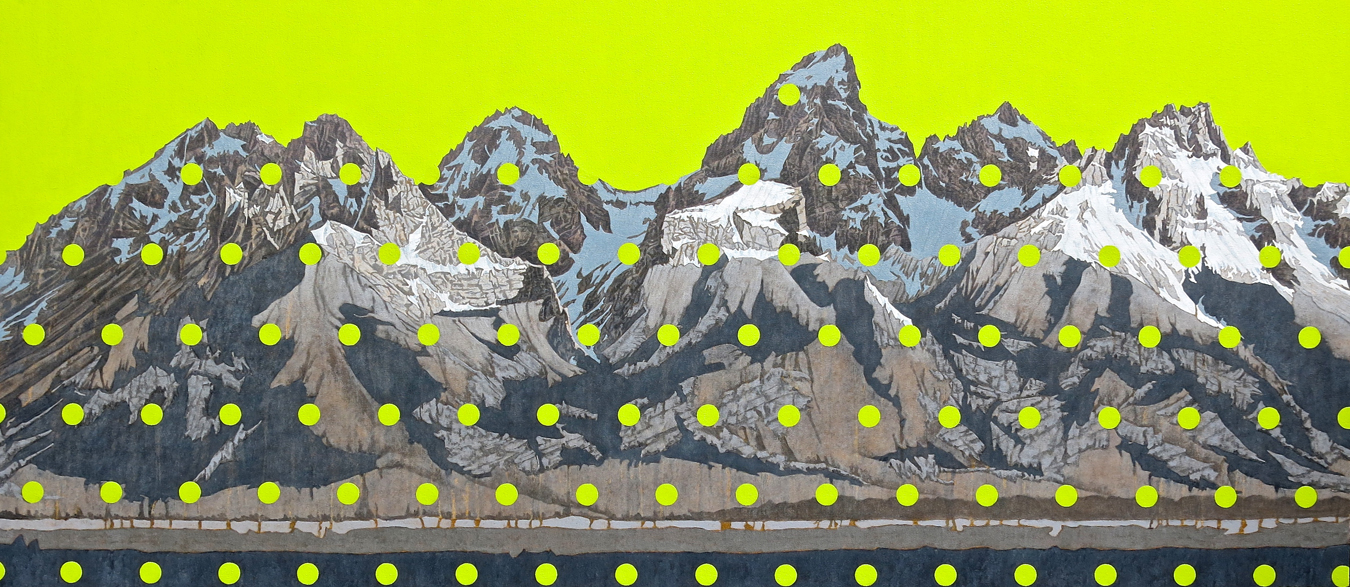

In many ways, Vancouver-based painter David Pirrie renders the very un-sublime. Washed with bright, almost clownish skies and gridded out with obstructive, flattening dots, Pirrie’s swaths of rock are a completely two-dimensional portrayal. Adding to that is the fact that Pirrie isn’t exactly timid when it comes to confronting nature. In a most literal of method studies, for nearly every mountain the artist has painted, he has climbed, traversed, and often skied down the rocky face. “I grew up in North Vancouver, and I always was wondering what was on the other side of the North Shore Mountains,” he recalls. “I remember asking what was there and no one could ever tell me.” Pirrie’s curiosity and interest in art took a long road before finally meeting on his canvases. “I started going further and further in my explorations, joining the mountaineering club, and then I went to art school and they were separate for a long time,” he says. “And then I started bringing together all my different interests—architecture, cartography, and mountaineering—and it was like, ‘Voila!’ I’ve really hit on something deep and personal to me.”

With paintings including Mt Robson Icefall, Mt Robson Grand, Mt Sir Douglas, and Mt Alberta South (all of which are showing in a solo exhibition at Ian Tan Gallery this spring), his work’s titles double as a journal of his mountaineering escapades. However, rather than feeling their monumental scope, Pirrie’s reproductions, while topographically accurate, are bite-sized studies. Presented in isolation from their massive geographic chains, each peak is carefully and methodologically examined, transforming a landscape into pensive still life. “It’s something that felt intuitive,” he says of the process. “I think that maybe the way I isolate subject matter started in art school. There’s something about the isolation of the matter—not a blank space, but a reference in studying the subject matter much more closely.”

Placed overtop of Pirrie’s Warhol-coloured still life landscapes is the rather perplexing addition of an opaque grid of circles. “I think the question I get asked the most is, ‘What do the dots mean?’” says the artist. Partly a reference to Pirrie’s utilization of cartographic tools, the dots are also a means to help disjoint and disrupt any easy classification. “It’s a formal element—it’s also kind of intuitive in terms of spacing and colour—it’s definitely a formal decision. It’s a little built on the scientific side in terms of how I grid it out and the map behind it,” says Pirrie. “I think that’s kind of why I’m putting these contemporary references on top of the painting: to keep it out of referencing just landscape painting.” Although Pirrie’s mountains operate outside of the landscape canon, each painting portrays a sense of amazement, but on a much smaller, more intimate level. His sublime is compact, bringing a personal connection to each of the grand peaks on the canvas.

_________

Read about the finer things in life. Visit our Arts page.