Vancouver’s real estate industry is largely fueled by the idea of impermanence. The city’s heritage buildings are often stripped to their shells to make way for slick city condos, while low-income housing sites are sold to developers to make way for modern dwellings.

For artist James Nizam, home is a word full of innuendo. A graduate of the University of British Columbia, Nizam had his first gallery show at the Surrey Art Gallery in 2002. Titled “Inventing Space(s): Three Artists’ Interventions in the White Cube”, the project opened his eyes to the idea of abandonment. Shortly after his debut, Nizam started photographing the original Woodward’s building, for example, or roaming Vancouver’s industrial sites to capture “vacant sites of play,” as he calls them. “When I started in 2002, the city was a different place. I discovered little squats and started to think about homes. That is now the root of a lot of my work.”

Thirty-three years old and with bright green eyes, British-born Nizam grew up knowing several homes. As a baby he lived in the Borneo jungle in Brunei. As a young child he lived in Muscat, Oman. And when he was a teen his family immigrated to Canada. “Home is a pretty loaded metaphor for me,” he says. In 2006, Nizam exhibited a body of photographs appropriately named Dwellings. The work was a near encyclopedic look at soon to be demolished homes, with catalogue-like detail of possessions left behind: old couches, dirty drapes and piles of used videotapes. Far from exhibiting a place where memories were born, these haunting photographs were taken well past the witching hour, and accomplished through the act of breaking and entering. “You kind of stalk the houses,” he says when asked how he chose his subjects. “You also become familiar with demolition.” To complete the work Nizam, entered his chosen subjects late at night, and then painted out their empty spaces with a flashlight, using only this light and a lengthy shutter speed to create haunting images of homes that have now all but disappeared. In some instances, Nizam played with the space itself, rearranging found objects to make them look more, or less, constructed. Other times the spaces were left as is, their used mattresses and worn-out armchairs photographed in all their dilapidated glory. One can’t help but wonder about the lives lived in these sad, haunting glances of what was once a place called home.

“Every photographer wants to take pictures of abandoned buildings. For me, it’s more about a space that’s between something. The hard thing is to keep the images poetic.”

Nizam’s next series of photographs, in 2007, titled Anteroom, also played on the idea of abandonment, but for this work he no longer confined himself to late-night acts of artistry. Using the basic elements of a camera obscura, deserted interiors become a canvas for the outside world—a place where rhododendrons bloom and excavators make way for newer, shinier residences. The images are made more haunting by the effects of the camera obscura, which flips its projection onto the flat, soon-to-be demolished walls of the rooms, creating a topsy-turvy world of Vancouver dwellings. “Every photographer wants to take pictures of abandoned buildings,” Nizam says. “For me, it’s more about a space that’s between something. The hard thing is to keep the images poetic.”

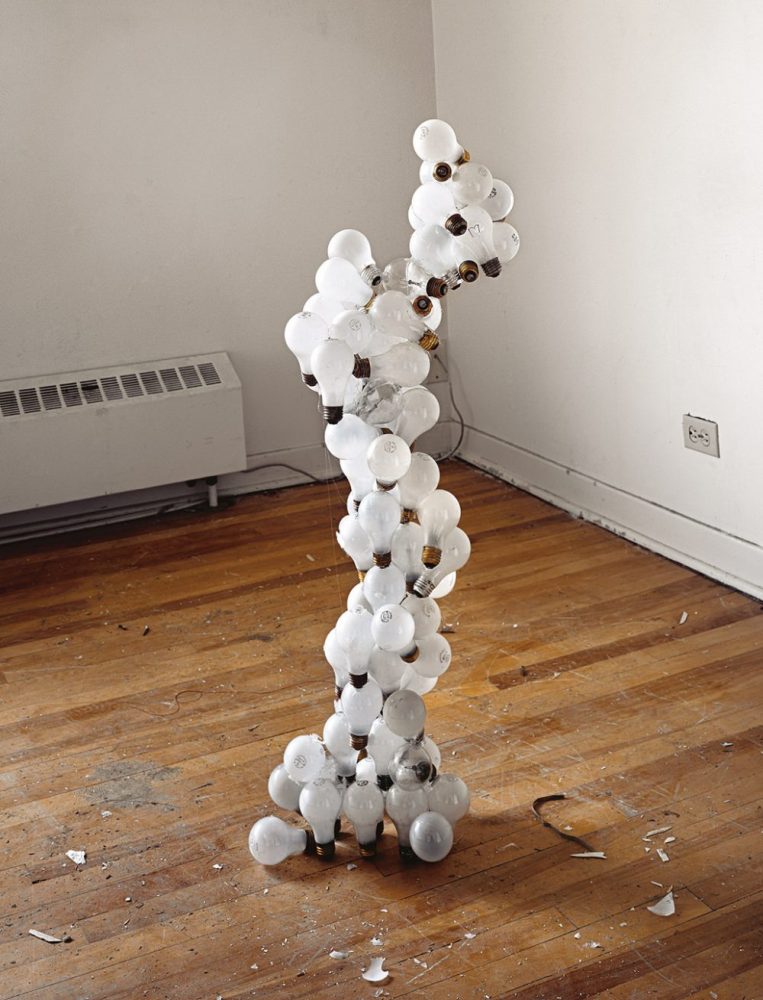

If poetic imagery is what Nizam is seeking, then he succeeds with his latest series, Memorandoms. Shot at the hotly debated public housing site Little Mountain, these photographs capture former low-income housing units with strategically placed piles of jumbled door frames, scrap metal and leftover parts. With the key to 224 individual apartments in hand, “all I found was that everything had been cleaned out.” And yet using the shelves, chairs, light bulbs, doors, and pipes left behind, Nizam has created a haunting space occupied only by sculptures. “I present you with this beautiful decay but I want you to question it,” he says. The Little Mountain site has been a controversial one, but there is a calm exuded in Nizam’s portrayal of these empty spaces and their neglected parts. Ironically, in order to complete the work, Nizam had to take up his own form of residence at Little Mountain, shooting for days at a time and spending nights there, in order to capture the space in all its gravitas.

“Every space I have shot no longer exists,” Nizam says about his ephemeral subjects, including those in Memorandoms. Similar to the constructed spaces of his earlier work, the impermanent sculptures he created and captured on film were destroyed shortly after shooting was complete. To Nizam, it seemed only natural.