When Gwaai Edenshaw was 16, he attended an assembly of the Council of the Haida Nation and spoke about how school was failing him.

“I was wasting my time in school, didn’t know my times tables, didn’t know a noun from a verb. I challenged the committee to not just let us kids drift.”

Haida master carver Bill Reid was in the room and, after learning that the young man speaking passionately about his frustrations was interested in art, invited Edenshaw to apprentice with him. Edenshaw’s father, Guujaaw (Gary Edenshaw)—also an artist—had worked with Reid on projects including The Raven and the First Men sculpture and the Skidegate dogfish pole.

“My dad was happy to see me leave school,” he recalls.

Edenshaw, now an artist and filmmaker in his own right (he co-directed the first movie made in the Haida language, the award-winning 2018 film Edge of the Knife), was approached last year by Vancouver’s Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art to curate a major exhibition to celebrate Reid’s centennial year. The result—“To Speak with a Golden Voice”—will open in April and run until early October.

Bill Reid with his sculpture Raven and the First Men, c.1980. Photo by Bill McLennan, courtesy of the UBC Museum of Anthropology.

“I owe so much of who I am and where I am to Bill,” Edenshaw notes. “I was happy to be a part of a celebration. I just figured it would be the least I could do.”

Narrowing down the scope for an exhibition of Reid’s achievements was no easy task. Edenshaw came up with four themes: Voice charts Reid’s time at the CBC, archival recordings, and vast collection of writing; Process presents rarely seen artifacts including Reid’s sketchbooks, drawings, paper maquettes, and moulds; Lineage gathers works by other artists such as Robert Davidson, Beau Dick, and Joe David; and finally, Legacy intends to bring a new perspective to Reid’s work and, (controversial at times) life, with a collection of short films featuring the insights and recollections of those who knew him, including fellow artists and friends.

“We wanted to build an exhibit around ideas of showing Bill’s personality, rather than just the work,” Edenshaw explains. “We’ve approached people who apprenticed or worked for him in various capacities. We want to do justice to his memory, but we really wanted to build something on Bill that hasn’t really been seen—which is a pretty big challenge, considering he is one of the most famous Pacific Northwest artists ever.”

To help organize the material, Edenshaw says he imposed a threefold filter: “The first is to prioritize works that haven’t been seen that much. Then I wanted to look for things that have a bit of a story behind them, and third, the work has to adhere to the principle of the well-made object. I’m looking for pieces of excellence.”

Edenshaw has also commissioned new works for the exhibition from two women artists. Haida Gwaii–based carver and painter Cori Savard (Yahgu’laanaas Raven clan) will create a piece inspired by Reid’s legacy.

“Cori is an incredible artist who has worked with Robert and Reg Davidson,” Edenshaw observes. “She will deliver both on creativity and excellence, and I wanted to showcase an artist who hasn’t received the kind of exposure they deserve.”

The other commission is from internationally renowned Canadian Mohawk musician, artist, and activist Kinnie Starr, who will take portions of Reid’s vocal archive and remix them with music into an abstract audio installation that addresses both Reid’s story and ongoing issues of Indigenous identity.

Many artists apprenticed or worked with Reid, and there have been claims that he took too much credit for work he did not personally execute, particularly when his Parkinson’s disease took hold. Edenshaw tackles that claim head on: “There is no expectation in the Western art world that the artist has his hand on every piece,” he insists. “What this criticism does is uphold the myth of Indian crafts. And it is a standard no one else is held to.”

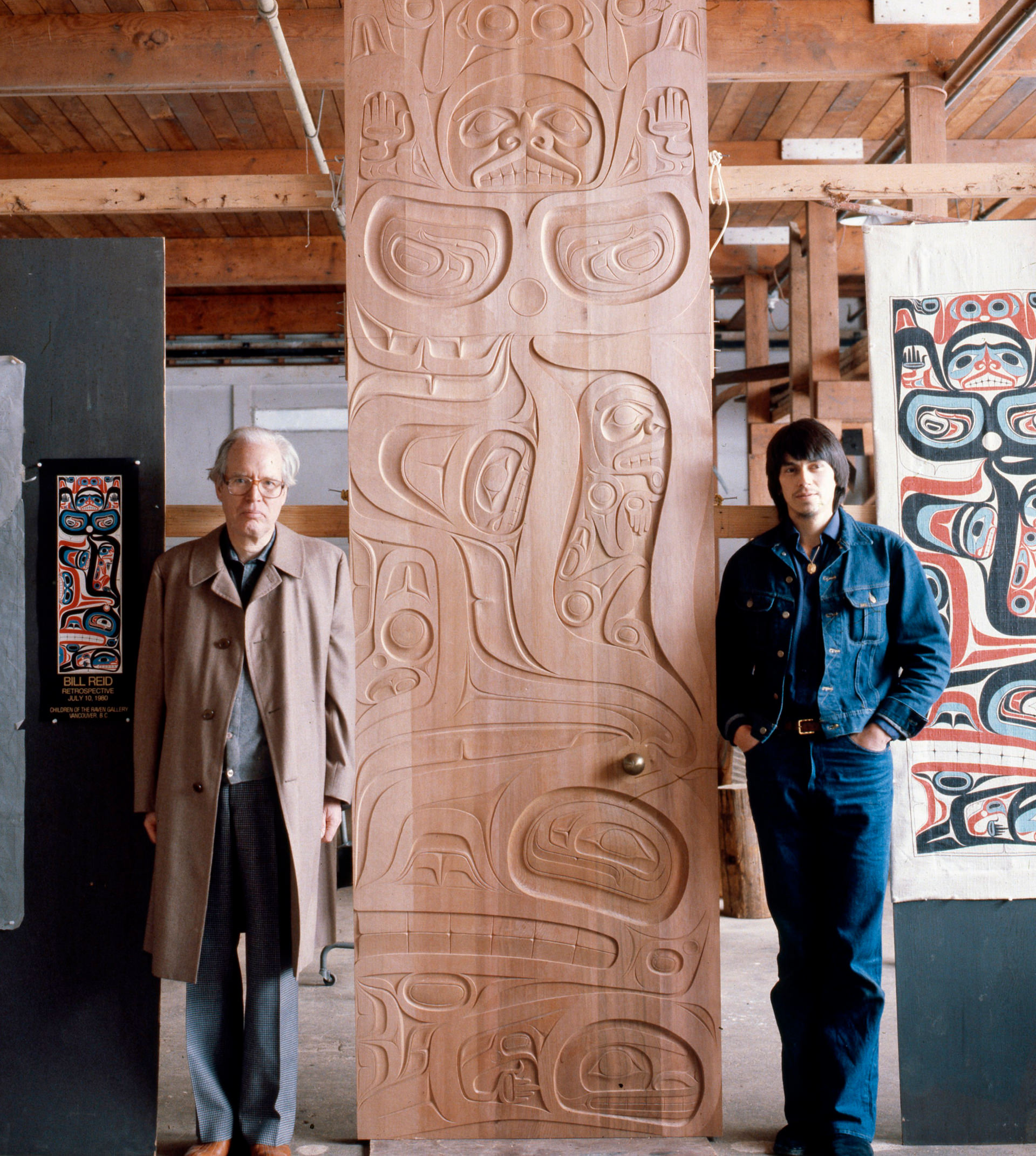

Bill Reid and Jim Hart, 1981. Photo by Bill McLennan, courtesy of the UBC Museum of Anthropology.

Yes, Edenshaw admits, Reid could be gruff in his dealings with his apprentices. “My feelings were hurt at times when I showed him a good piece and he would tell me it was wrong, but the reason I could become an artist, and there was work here if I wanted it, is because we inherited an art legacy. We didn’t have to work to create this marketplace.

“So many people moved through Bill’s studio over the years,” he adds. “It might have happened without him—the art is intrinsically powerful in any number of ways, it could have still been discovered. But there are very few who can’t draw a line back to Bill.

“It could have happened without him,” Edenshaw shrugs. “But it didn’t happen without him.”

This article is from our Spring 2020 issue. Read more about the Arts.