Nothing on this quiet street would suggest you’re standing on a natural division of Vancouver geography. Somewhere here—it’s hard to tell exactly where—two raindrops could fall side by side, and one might roll west down the slope toward Nanaimo Street, join a trickle of water into the MH4 maintenance hole, and travel seven kilometres of storm sewers to join the salt water of the Pacific near the Cambie Bridge. The second might roll east, filter through the bank of the ravine into Still Creek, tumble down the hill to turn east, dodging through culverts and under roadways to flow into Burnaby Lake, then rush down the Brunette River to join the Fraser, and loop back west to the sea.

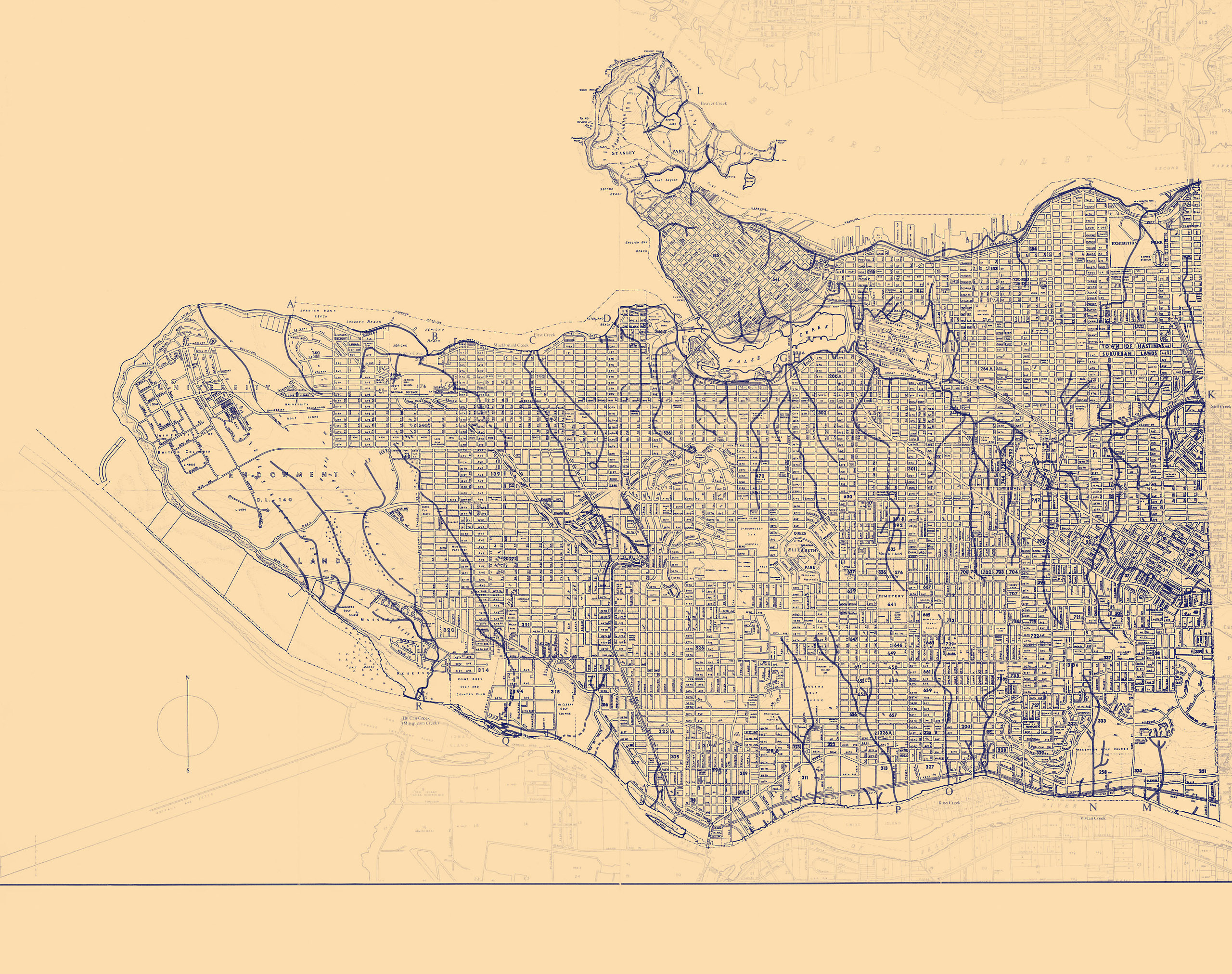

The watersheds of Vancouver are invisible because we have made them invisible. Over a century and a half, British Columbian settlers have paved over, filled in, or diverted nearly all 120 kilometres of waterways that once flowed through what is now Vancouver. The last salmon-bearing streams in the city are Musqueam Creek, protected and rehabilitated by the Musqueam First Nation at the mouth of the Fraser River, and Still Creek at the city’s eastern edge, an afterthought untouched more out of neglect than conservation.

“We’re kind of lucky the ‘bury everything’ mentality never quite got this far,” Carmen Rosen tells me as we hike up Renfrew Ravine. An artist living in the neighbourhood just east of Still Creek, Carmen runs the Still Moon Arts Society, which cares for the ravine and celebrates it with an annual autumn festival.

In a whimsical hat pinned with felt birds and animals, Rosen leads me upstream surrounded by the peep peep of ruby-crowned kinglets and the faint smell of sewage. Decades of work by volunteers have brought life back to the ravine, though the steep slopes are choked by cascades of invasive Himalayan blackberry and English ivy.

The creek abruptly disappears into a hillside at 29th Avenue, but we continue south, upward past the SkyTrain station and into the residential Collingwood neighbourhood, Rosen pointing out the natural dips in the city streets where the creek once flowed. After two blocks, embarrassed, I have to pull out my phone to regain my sense of direction.

When I moved to Vancouver, I lost my sense of topography. Growing up in the mountains of Interior British Columbia, my mental map of the land was delineated by creeks and streams and bounded by the shores of a lake. In the city, my new map is a symbolistic network of SkyTrain stations, bus routes, landmarks, and intersections.

“Noticing the geography of the city, the topography of it, the makeup of the city, the flora, the soil—water enables that,” Jimmy Zammar, director of integrated strategy and utility planning for the City of Vancouver, tells me later over the phone. “The city is shaped by water, quite literally.”

Zammar works on the city’s strategy to transform the way water flows through Vancouver. This year, narrow trenches of trees in the dense urban blocks of Richards Street between Pacific and Cordova will begin to absorb 11 million litres of rainwater per year. An ongoing project at Tatlow Park in Kitsilano will “daylight,” or resurface, sections of a buried stream that once carried spawning salmon.

“These spaces bring back an aspect of the city that has been forgotten from collective memory,” Zammar says. “They’re not only critical drainage assets, but they also have a critical placemaking role.”

“These spaces bring back an aspect of the city that has been forgotten from collective memory.”

Below the ravine, Still Creek dips through a culvert under 22nd Avenue and reemerges just west of the Renfrew library, where I pick up a faded and Scotch-taped copy of Vancouver’s Old Streams, a slim volume published in 1978 by local historian Sharon Proctor. In meticulous detail, it catalogues the staggering loss of Vancouver’s waterways: hundreds of thousands of salmon and sea-run trout spawning up 50 creek mouths, the lifeblood of an ebullient ecosystem of seabirds, trees, berry bushes, fungi, elk, deer, and bear—all paved over in the blink of a historian’s eye.

There is something transformative about becoming aware of Vancouver’s missing water, something that once seen cannot be unseen.

“What happened to me is what happens to a lot of people,” Celia Brauer tells me. “If you get water, you get everything. If you know what watershed you’re living in, you think differently.”

An anthropologist, writer, and artist, Brauer helped found the False Creek Watershed Society after moving to Vancouver and becoming captivated by the history of the vibrant marshy flats that once stretched east across what is now rail yards.

“We all seem to dream this stuff,” she says. “There are a lot of us water people. We look out the window, and we can see what was there.”

Once Still Creek reaches the shallow valley between the heights of Collingwood and Willingdon, it dodges and weaves east past warehouses and big box stores, impossible to follow over chain-link fences and parking lots, often only visible by a telltale row of blackberry brambles.

Where the water flows there is life, though; a ruby-throated hummingbird buzzes in the branches of a blossoming salmonberry; a downy woodpecker attacks a dead elm tree; a crow bathes in the shallow clear water. In the past year, students at Langara College have studied the lower creek and found invertebrates, cutthroat trout, staghorn sculpin, and chum salmon spawning.

Two kilometres south up the ridge, Rosen and I reach our destination at Kingsway. In a plaza between a bubble tea shop and a hair salon, stone fish sculptures leap out of the paving stones—a project Rosen envisioned to mark where the upper reaches of Still Creek once flowed.

Standing in the plaza, looking out over four lanes of traffic and the hubbub of Norquay Park, you can strip away the layers of history. The legendary Wally’s Burgers was founded here in 1962, just as Vancouver struggled to fix its messy network of drainage sewers and install a treatment plant at Iona Island.

A 1912 insurance map shows the upper creek still open to the air, ducking through culverts only at the larger avenues, a source of easy trout-fishing. The open stream ends only at the New Westminster Road, which would become Kingsway. Before the road was built in 1860, a long beaver-dammed lake spread southeast—drained by the Royal Engineers to make way for the town of Collingwood. Before that, old-growth forests of cedar, hemlock, and Douglas fir, and thickets of salmonberry and thimbleberry surrounded ancient Indigenous trails leading across the ridge from the fork of the Fraser delta to the villages of Burrard Inlet.

On one of the fish statues, an inscription in the Skwxú7mesh language reads:

“Wa7t kex ta kwusn wa esxwéyxwey kwi kwekwi’n’. Xwi hawk stam na wa kw’áchnexwaxw i ti’wa.”

“There used to be a lot of stars showing before. Now you don’t see them anymore.”

The water is gone too, but if you listen carefully you can almost hear it gurgle beneath your feet.

Read more from our Summer 2021 issue.