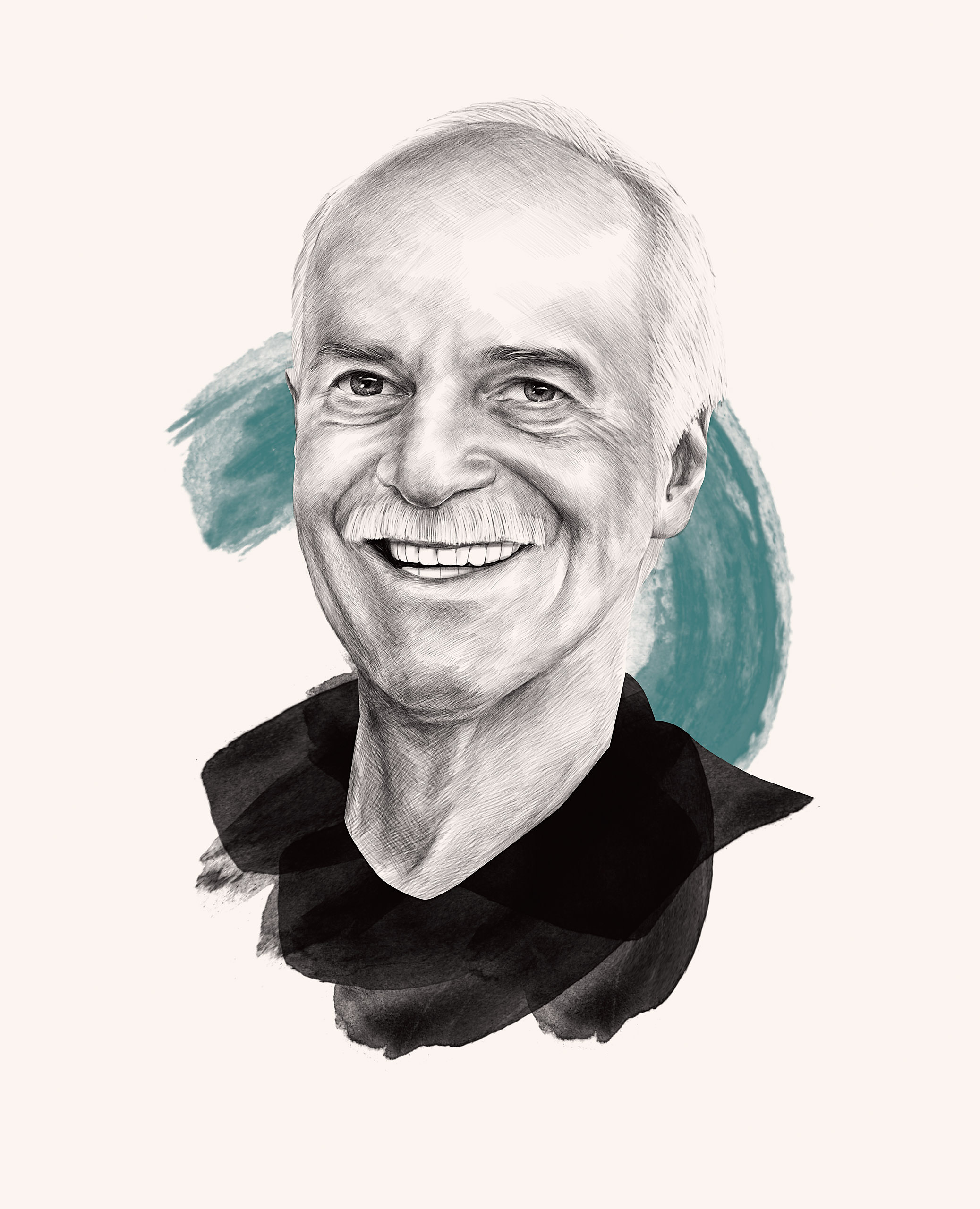

The story of how Jack Evrensel ended up in Whistler—launching a restaurant that spawned an empire, selling it all, and, after an eight-year hiatus, making a triumphant return (more on that later)—starts the way many stories do in this mountain town.

“The idea was to open a business and be able to ski all day and work all night. It wouldn’t really be work—it’d be fun,” he says with a chuckle, recalling his 26-year-old naiveté as we chat in the lounge of the Aava Whistler Hotel. “The idea was very romantic.”

The year was 1980, and Evrensel and his wife, Araxi, had decided to flee Montreal—where the two immigrants (he born in Istanbul, she in Cairo) had met in school. “We knew we had to leave Montreal because we were English-speaking and had a young son,” Evrensel says, describing the tense lead-up to the 1980 referendum on Quebec’s independence.

One night, the Evrensels were out for drinks at a bar in Montreal with childhood friends, an Armenian couple who had recently returned from a ski trip in Aspen. The friends talked about Aspen in glowing terms—but reported that the only thing missing was a crêperie. Crêperies were all the rage in Montreal at the time, and soon the wheels were turning inside their twentysomething heads. Wouldn’t it be cool to open one in some Canadian ski town? On the back of a cocktail napkin, a plan was hatched.

Later that year, the two men drove to the Rockies, thinking Banff would be the site of their new venture. Not impressed with Banff, they kept heading west until they arrived in Whistler. “I went into a real estate office—and remember, there was no village at the time—and they showed us a rendering of what the future village would look like. It was beautiful.”

Evrensel and his partner quickly signed a lease for what was to be the location of their crêperie. But after many delays in construction—and divergent ideas among the partners about what the concept should be—the Evrensels parted ways with their Armenian friends, giving up ownership in the venture. They had already signed a lease on a space in Blackcomb Lodge for a restaurant to be named after Araxi.

Araxi opened on Halloween 1981—and the first few years were indeed scary. “I had some very difficult times,” Evrensel recalls. “I was operating on a shoestring, borrowing money, and working day and night to survive.” Evrensel fought his way through a brutal recession, double-digit interest rates, and Whistler’s uncertain future (the Crown corporation overseeing development was on the verge of bankruptcy in the early ’80s). But eventually, his restaurant at the heart of Village Square found its feet and a loyal clientele. (He also opened a nightclub next door called the Savage Beagle Club, followed by 1st Run Designs clothing and jewellery shop.)

Araxi would go on to become one of the most acclaimed restaurants in B.C. and help put Whistler on the dining map. The success of the Whistler businesses allowed Evrensel to expand into the competitive Vancouver market a decade later, where he launched a series of upscale eateries, including CinCin on Robson Street in 1990, Blue Water Cafe in Yaletown and West in South Granville in 2000, and Thierry on Alberni in 2011. Under the corporate umbrella Toptable Group, Evrensel’s restaurants racked up a slew of industry awards, packed its rooms, and produced a generation of B.C.’s top bartenders, sommeliers, servers, and chefs.

In 2014, at the top of his game, Evrensel sold Toptable to the Aquilini family. Initially, he rebuffed the courtship. “They kept asking and asking,” he says, “but eventually I realized that there’s not really a model for a group like this to be sold—it’s easy to sell a chain, but these were all one-offs. I wasn’t ready to sell, but it made sense at the time.”

Which brings us to our chat in April 2022. Evrensel has been keeping busy for the past eight years with various real estate and investment deals, but at 68, he’s discovered he isn’t ready to quit the restaurant business just yet. “It’s in my blood. And I have something to say with this new place.”

This new place is Wild Blue: a fine-dining restaurant, bar, and lounge taking shape across the cul-de-sac from where we’re sitting at the Aava Hotel. Evrensel, Neil Henderson (his long-time restaurant director at Araxi and projects director at Toptable Group), and Alex Chen (executive chef at Vancouver’s Boulevard Restaurant) are equity partners in Wild Blue, each with distinct roles: “Alex is the bottom-line guy in the kitchen; Neil is the restaurant director, overseeing everything; and I’m the restaurateur who’s going to set it up and set its course.”

Asked what he’s trying to say with Wild Blue, Evrensel waxes philosophical. “In this business, every sense is involved. And every sense is a deep dive, from the food to the wine to your surroundings to what you’re hearing. And it’s not just music you’re hearing—you’re creating music with people,” he says. “I want them to have an amazing experience, with all those elements.” The restaurant—focused on what’s described as “elevated Pacific Northwest cuisine”—will have seating for 150 guests indoors, with room for another 58 on a secluded outdoor patio. The grand opening—delayed by COVID-19—is now expected this summer.

Evrensel and his partners are entering what has become a very competitive market. Vancouver’s iconic Joe Fortes expanded to Whistler last August, taking over the Sundial Place location previously occupied by Trattoria di Umberto. And Toptable under the Aquilinis has also expanded its Whistler footprint—doubling the capacity of Bar Oso (next to Araxi) and opening a new eatery in the same block; both are expected to launch in 2022, according to Toptable’s VP of Whistler operations, Geoff Lang.

While all this activity is a sign of strength for the local dining scene, Whistler remains one of the most expensive places in Canada in which to live and work. And coming out of COVID, many Whistler restaurateurs are struggling to staff up to meet exploding consumer demand.

“It’s never been this bad,” Evrensel says, describing the current labour challenge. (Executive chef Derek Bendig, once sous chef at Fairmont Chateau Whistler, and most recently executive chef at Rossland’s Josie Hotel, was only hired in May.) “Then again, it’s never been easy. There’s always been a shortage of talent.” That said, he notes that the lifestyle has historically drawn an eclectic mix of workers to Whistler: “One year, we had three hostesses at Araxi who were lawyers—they’d each taken the winter off to ski.”

Diana Chan also moved to Whistler for the lifestyle: an avid skier, she retired from an executive role with a Vancouver credit union in 2016 to buy the popular Moguls Coffee House in Whistler’s Village Square. Since January 2020, she has served as chair of the Whistler Chamber of Commerce—and while Chan is encouraged by tourism’s bounce back, she worries about the ability of her members (including Moguls) to find workers in the wake of the pandemic.

“In Whistler, we are very dependent on temporary foreign workers (TFW) and people in what I call the gap-year employment cycle,” Chan says. “A lot of those people went home during COVID. There’s so much uncertainty for our labour force, for the business.” The chamber (among others) successfully lobbied to have restrictions on recruiting abroad lifted for tourism-based jobs and to raise the percentage of TFWs restaurants can bring in. But Chan says the changes, announced by the federal government in April, come too late for the busy summer season. “Now I’ve got to get all my applications ready—so we’re looking at next winter.”

Chan, like many business owners, also has her eyes trained on the intractable housing issue. While Whistler counts only about 14,000 permanent residents, its “population equivalent” (permanent residents, seasonal residents, and the average number of visitors in Whistler on any given day) can double or triple that tally, depending on the year. (The number of annual visitors has almost doubled since 1997, to over three million a year, according to the municipality.)

“For every visitor, how many employees do we need to support that guest experience?” Chan asks. “The ratio is not one-to-one—it’s more like five-to-one. We need a tenfold increase in our housing.” Some employers, in an attempt to mitigate the crisis, have built housing for their seasonal workers; Toptable’s Lang estimates 30 per cent of his Whistler staff receive subsidized accommodations from the restaurant group.

Despite these challenges, almost everybody in town seems bullish about the future—especially on the dining front. The Village Stroll is as packed as ever, with tourists and locals alike eager to break loose of their pandemic shackles and embrace a night on the town. Even Wild Blue’s prospective competition welcomes a splashy new entry from the former boss. “During those busy summer nights, we’re constantly having to turn people away,” says Jason Kawaguchi, Araxi’s manager and wine director. “There’s more than enough business to go around.”

As for Jack Evrensel, he says he’s looking forward to getting back in the game. He admits to being unable to set foot inside Araxi (or any of his former Toptable restaurants) since selling back in 2014—“it’s just too hard,” he says—and while he doesn’t plan on recreating an empire, he muses about opening another restaurant somewhere down the road.

“Not in Whistler, but if I found the right location in Vancouver, we could expand. So yes, there might be something else,” he says, a twinkle in his eye. “The future is not written.”

Read more stories from our Summer 2022 issue.