When Dani Gal stumbled upon an old vinyl record documenting Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, he was unwittingly using the past to open a door to his future as an artist. Gal was born in Israel but has lived in Germany for more than 20 years. He discovered the Six-Day War Victory Album in 2005 and for the first time became aware of the phenomenon of spoken-word political and historical albums. He began to seek them out, and as he discovered more and more nonmusical albums of speeches, documentaries, and recordings of historical events, he thought about the reasons they were made, purchased, and listened to.

“This phenomenon of putting historical and political records on vinyl really fascinated me,” says Gal, who is displaying 246 albums from his collection of 700 historical records at the Polygon Gallery until July 14. “It took a while for me to realize why it was so interesting. Recorded sound for me is fascinating because it has an uncanny ability to bring an event so close to you while using a recorded medium that is really rather primitive. Because it is spatial, it gives you a feeling that something is happening right now in a way you don’t get with film.” But what motivates us to replay a record of a speech as if it were a piece of music? “That is the moment where the collective touches the personal. You are reliving your nation’s past and everything that is behind it—propaganda or collective memory construction and so on.”

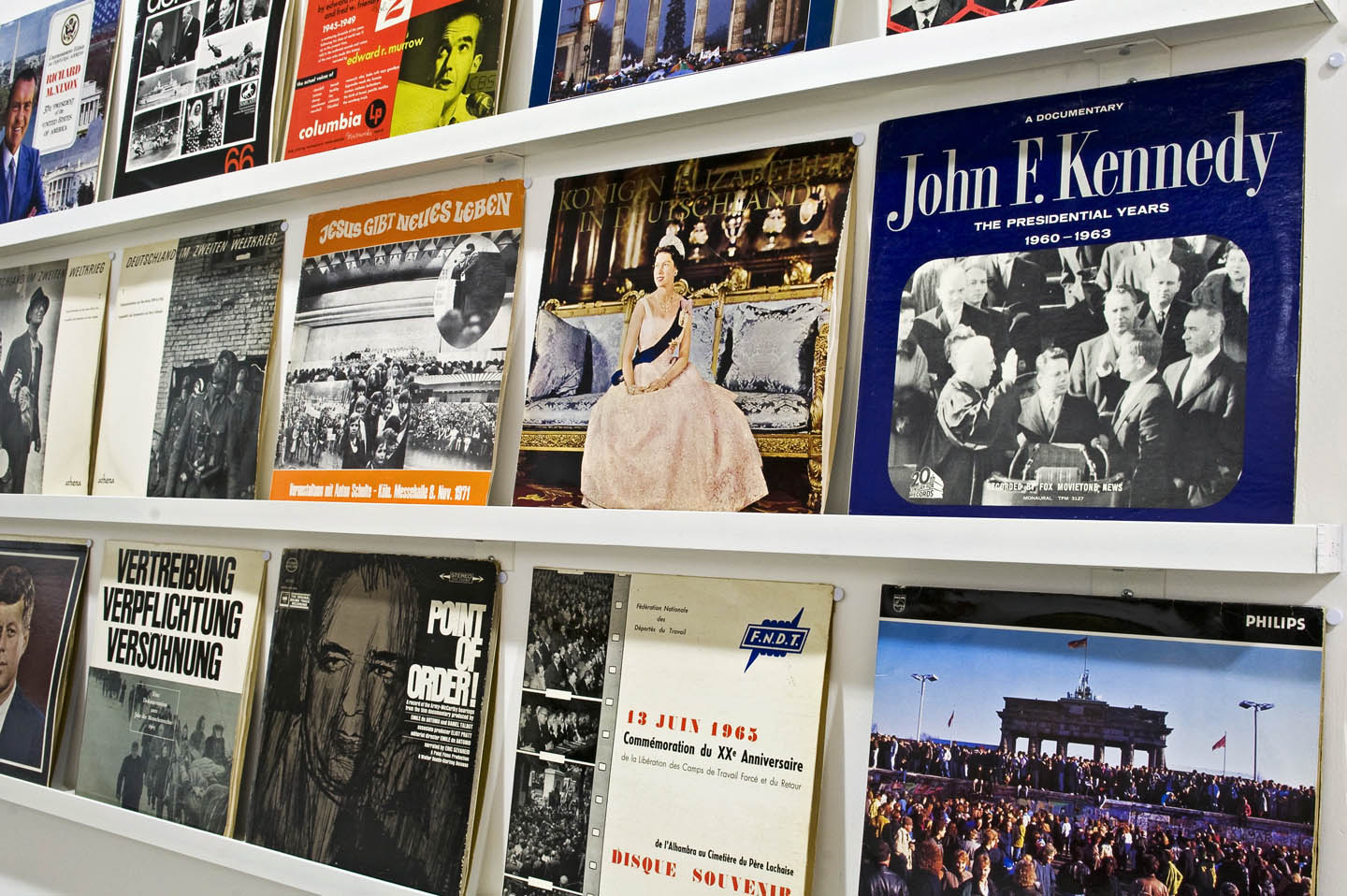

Gal’s sweeping collection tells a partial history of the 20th century, covering everybody from Gandhi and Goebbels to Golda Meir and Gamal Nasser. Most of the collection is documented on his website, which includes audio and photographs of covers. Browsing it opens holes in time. There are albums dedicated to the moon landing, the 1968 Paris riots, the Black Panthers, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and Winston Churchill’s funeral. There are dozens featuring speeches by JFK, who, Gal jokes, “made more records than Bob Dylan.” The existence of some—speeches by Martin Luther King Jr. or a recording of a VE Day celebration—makes more sense than others: how many people purchased Spiro T. Agnew Speaks Out when it was released in 1970? From Canada, there are albums dedicated to the speeches of Pierre Elliott Trudeau and Tommy Douglas, as well as Canadian and American documentaries about the Armenian genocide and Alan Shepard’s flight into space. Vive le Québec Libre! features excerpts from Charles de Gaulle’s speeches.

It’s notable that the ongoing vinyl revival does not seem to include a hunger for political records. Their heyday was the 1960s and 1970s, when people desired a way to relive the political present.

Edison envisaged the phonograph as a means of recording speech, but Gal says spoken-word albums have their roots in the aftermath of the First World War, when they were created for soldiers who had been blinded in the trenches. Their rise and fall charts that of vinyl as a whole, from the invention of the LP by CBS in 1948 to the arrival of the CD. It’s notable that the ongoing vinyl revival does not seem to include a hunger for political records. Their heyday was the 1960s and 1970s, when people desired a way to relive the political present, an analogue equivalent to podcasts or YouTube. It seems significant that the final albums in Gal’s collection are from 1989, a totemic political year with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the “end of history.”

Gal first became conscious of spoken word as an audio form through its use as samples in dance music and hip-hop. Part of the fascination of the collection is seeing the vinyl record—an object of desire and glamour that we associate with pop stars from Frank Sinatra to Taylor Swift—used to celebrate papal pilgrimages or the speeches of Helmut Schmidt.

Dani Gal, Historical Records part 1 of 3, at the Istanbul Biennial, 2011.

The Dani Gal: Historical Records exhibition is accompanied by a chance to listen to recordings and a one-off performance by the artist of a sound collage called Semi-Automatic: The Swamp in June. “There will be a turntable to listen to the records and a computer to hear my radiophonic works,” Gal says. “I did a project where I made a radio show 20 days each of 50 minutes, which takes these historical events, and made sound documentaries with interviews, quotes, and abstract sounds all from the records.” Visitors can access this at the exhibition.

Gal is displaying the records along an entire wall of the gallery, with the order influenced by colour and design rather than content or chronology. He deliberately avoids making cute, obvious, or ironic political and historic connections. He prefers the viewer to make their own journey into the overlapping histories presented by the albums, influenced as little as possible by Gal’s own views.

Gal often works with sound in his art practice, making collages, installations, and films. Additionally, he has made several short films that explore aspects of the relationship between Israel and Germany, as well as between the past and present, with a particular focus on what he describes as “historic blind spots” such as the disposal of Adolf Eichmann’s ashes after his execution. His record collection acts as a backdrop to these other projects, providing source material and influencing him both directly and indirectly.

“I have learnt so much from these records,” he says. “It is fascinating how some of these people spoke, and it is amazing to hear the talent of some of the speakers. It is also the content and the context. The best ones for me are the records that are about a single event, and they are quite rare as they are usually moderated or represented as a collage. When it is documenting one event, it is very powerful. We call them time documents in Germany.”

Dani Gal, Historical Records, at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2023.

Gal is aware of the absences in the collection—countries, communities, or individuals that did not have access to the means of production and distribution required to make such records. So while he has found dozens of albums from Israel, including recordings of the Six-Day War in Hebrew, English, French, Danish, and Yiddish, there are few from Palestine. He says the Victory Album is a very strange record. “It represents this kind of victory euphoria that surrounded society after that war that obviously continues to live its nightmare.”

While the albums were not all created as crude propaganda, there are clearly many such recordings, and Gal thinks conditions haven’t changed much from when these records were on sale, even if nobody is clamouring to buy double LPs of Justin Trudeau’s greatest hits. “A lot of this material would sound a bit naive to us, but we still live in this nationalistic world,” he says. “Everything is very transnational, but nationalism is getting stronger. The economy and culture have crossed boundaries, but when you look at polls, people are very nationalistic, a reaction to the new liberal economy with people feeling uncertain so they go to the people who offer them false promises.”

Photos courtesy of the artist. Read more from our Spring 2024 issue.