“There’s a story missing,” says Lauren Moberly. Despite clues scattered across the 11,000 square kilometres of Jasper National Park’s forests, lakes, and mountains, Moberly, a member of the Aseniwuche Winewak Nation and the Mountain Métis, says many visitors overlook them. Some of the story lies in the park’s more than 700 archaeological sites, while other parts are hidden in plain sight: an abandoned homestead, scattered graves, and the trail that became Highway 40 to Grande Cache.

The highway is particularly poignant. “All the Indigenous people were evicted when the park was formed,” Moberly says. “It was such a big group: babies, elders, all their livestock. They travelled for almost two years in search of a home.” Disturbed by this made-in-Canada tale of displacement, I ask if the story is well known. “You won’t find it in the textbooks,” says Barry Wesley, a Stoney traditional knowledge keeper whose people were also driven out of the park. “We were erased,” Moberly tells me.

Wesley, a consultation officer and language protector from the Bighorn Stoney reserve, says the Stoney were the first inhabitants of the place now known as the Rocky Mountains. Set in the eastern foothills, near the headwaters of the Athabasca River by the Creator, he says, “The Stoney have been part of the ecosystem since time immemorial.”

In his story, the next to arrive were the Simpcw. Coming from the west, they spoke another language. However, Wesley’s ancestors believed they could coexist, so the Stoney and the Simpcw Nation struck a sacred treaty. Then, visitors from the east began arriving. Wesley says these people spoke so many different languages and came from so many places that treaties weren’t possible—according to Wesley, these newcomers never gained the same rights to the land as the Stoney and Simpcw.

![Ewan Moberly family in front of their house in Grande Cache. [1912] Pa 20-29. Photo courtesy of Jasper-Yellowhead Museum And Archives.](https://montecristomagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Feature-Jasper-Park_Page_1_Image_0001.jpg)

Ewan Moberly family in front of their house in Grande Cache. [1912] Pa 20-29. Photo courtesy of Jasper-Yellowhead Museum And Archives.

Then there are the Dane-zaa, Nêhiyawak, Anishinaabe, Ojibwe, Sioux, and Métis, each with their own hereditary connections. Thanks to the Athabasca River, which flows 1,500 kilometres northeast across Alberta, the Jasper Valley has long been a cultural crossroads where those from the east and west came to trade or steward resources. By the early 1800s, when both the Hudson’s Bay and North West companies were actively trading across the mountain passes, some 20 Nations had ties to the foothills, mountains, and valleys that would become Jasper National Park.

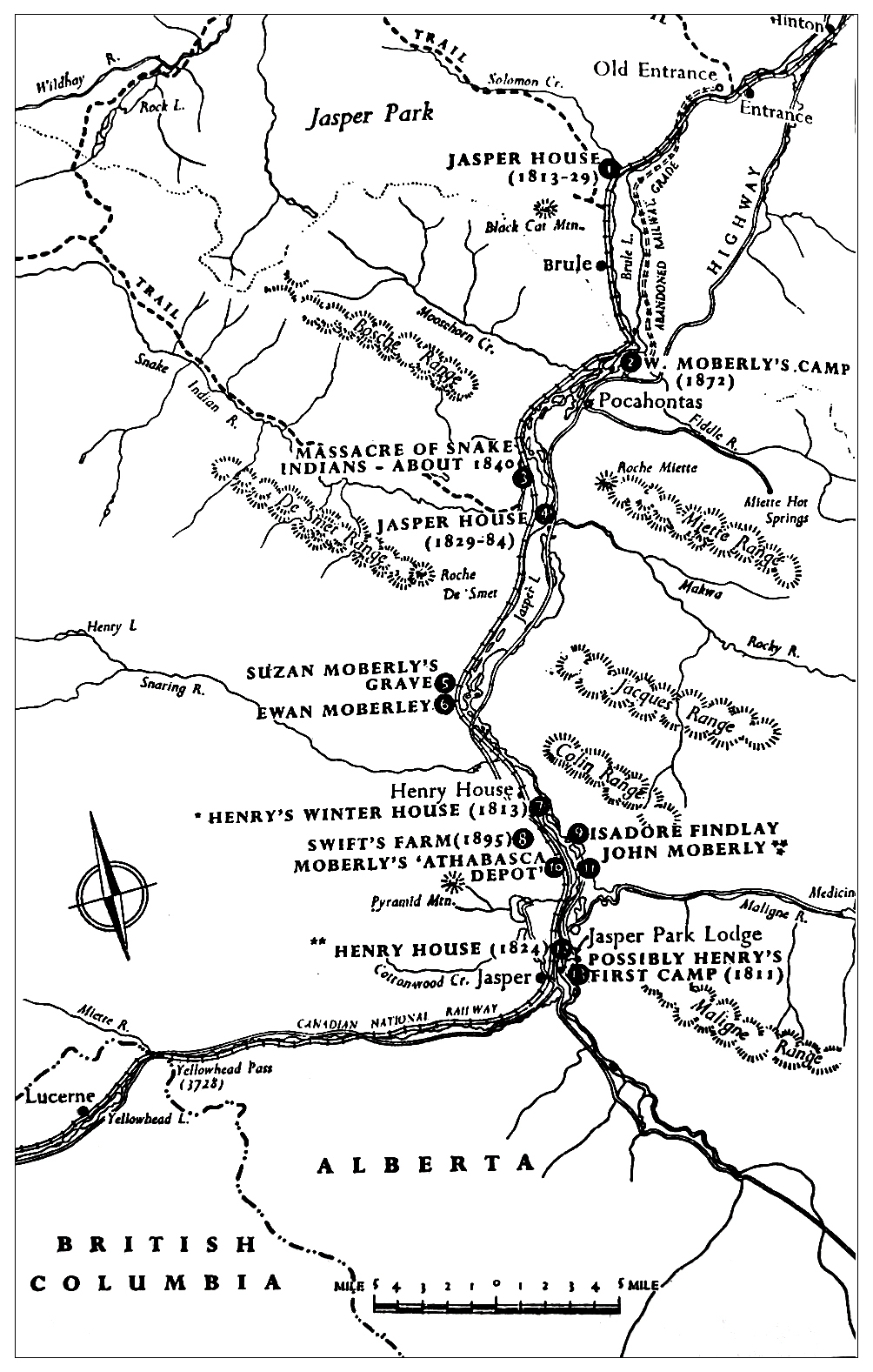

Image courtesy of Lauren Moberly.

In the decades that followed, some of these connections deepened, while others were disrupted. Moberly’s ancestors, who’d long made the Rockies home, settled into a permanent community of farms and homesteads. Other Nations, including the Stoney, were forced off their traditional lands and driven onto reserves as Alberta’s numbered treaties were signed between 1876 and 1899.

This is also when Canada’s first national parks were established. Scattered along railway routes, the parks were envisioned as majestic attractions and designed to bring in tourist revenues. Outside of luxury hotels and other amenities, visitors were promised pristine wilderness. So in 1907, as Canada’s second transcontinental rail line was poised to bring tourists to what would become Canada’s fifth national park, the problem of Jasper’s 100-plus settled “squatters” and nomadic “trespassers” was raised with the federal government.

What happened next is a bit murky. The Rocky Mountains Park Act, which governed the nascent park, stated that “no person shall locate, settle upon, use, or occupy any portion of the said public park” and left “the removal and exclusion of trespassers” up to newly appointed forest rangers. For Moberly’s ancestors, Ewan and Madeline Moberly, who were raising 10 children on a comfortable homestead with“two houses, a storehouse, five stables, sixty horses, eight head of cattle, and twelve cultivated acres,” this meant having their guns sealed or confiscated. Labelled by the government an “undesirable class” of people, they found their livelihood of hunting, trapping, and farming was now against the law.

The community in the Jasper Valley held out against the eviction as long as they could, but without firearms, they feared starvation or violence from the newly arrived North-West Mounted Police. While a white settler did remain (and was granted land), the rest were offered a small payment for their buildings and locked out of their homes. They were told they could resettle anywhere they wanted outside the park.

Photo courtesy of Lauren Moberly.

Departing the park in the spring of 1910, the families tried to settle near Cache Lake, Graveyard Lake, Rat Lake, Entrance, and Rock Lake. But each time they were forced to move on. It wasn’t until they completed a final 135-kilometre, one-year “great trek” from Entrance to isolated Grande Cache that they were left alone. “But we never forgot that Jasper was our home,” Moberly says.

The Moberly Family. Mr. and Mrs. John Moberly and Sons, Dave and Frank in their automobile. Pa 20/27. Courtesy of Jasper-Yellowhead Museum and Archives.

“What happened to Indigenous people in Jasper happened in national parks across Canada,” says Mark Young, Jasper National Park’s Indigenous relations and cultural heritage manager. Young, who helps administer the Jasper Indigenous Forum, an interest-based advisory group focused on returning Indigenous presence and culture to the landscape, has spent his Parks career “building relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.” According to Young, the 1982 inclusion of Section 35 in the Canadian Constitution, which acknowledges and upholds Indigenous rights, was a first step toward reconciliation. “Indigenous peoples recognized they were a fundamental part of what Canada should be,” he says, which pushed Parks Canada to start abandoning its exclusionary practices.

“What happened to Indigenous people in Jasper happened in national parks across Canada.”

Creating space for Indigenous people to reconnect with their traditional lands isn’t as straightforward as updating a few policies. Over the past four decades, Parks Canada has begun the slow process of building partnerships with more than 300 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities. Goals for each partnership vary, but most focus on strengthening Indigenous connections to traditional lands, sharing Indigenous histories with visitors, and increasing opportunities for Indigenous-led tourism.

Moberly, who is part of the Jasper Indigenous Forum, says for her community just feeling welcome, safe, and acknowledged in Jasper National Park is important. She explains that when her parents brought her to the park as a kid to teach her about her historical connection, there were barriers. “My mum would warn me if I even picked a flower, park officials would come get me.” Becoming a park partner has helped her build on her relationship to the land. She says she’s been able to teach her community about their harvesting and fishing rights and advocate for their history to be correctly included in interpretive information. But with more than 20 Nations claiming a connection to the park, competing goals and differing priorities can make getting things done fraught.

Photo courtesy of Lauren Moberly.

Moberly points to the much-contested October 2023 ceremonial hunt and treaty renewal by the Stoney and Simpcw, which they organized in consultation with Parks Canada. When the hunt was presented to the forum, Moberly says the news caused an uproar. Later, when the hunt took place near the family’s historic Moberly homestead, “it seemed like an insult.” But for the Stoney—who have made repeated land claims in the region—Wesley says it was an important expression of their rights.

Young says these inter-Nation disputes will take time, and patience, to unravel. “We’re taught that Canada had two founding nations—but there were actually hundreds of Nations with different ways of solving issues.” While the forum has been open to any interested Nation, it has also created smaller project-based advisory groups to tackle specific objectives, including educating park staff about diverse histories and managing the park’s cultural area.

This is also a transition time for park visitors, who occasionally misconstrue reconciliation as Indigenous people being given special rights. But scientists point out that we’re just beginning to understand how much harm was done not just to the First Peoples but also to the land and water when their caretakers were forcibly excluded. “The land was shaped by thousands of years of Indigenous stewardship and harvesting,” Young explains. It was never just scenic mountains, rivers, and wildlife—it was also humans.

Moberly says along with the frustrations that come with rebuilding connection and sharing her story, she also holds hope. The history of the Aseniwuche Winewak Nation will be included in the new Jasper Indigenous Exhibit, an interpretive display outside the Jasper Information Centre, which will contain the stories of many of the Nations linked to the park. The exhibit will also include the first formal apology to Indigenous Nations from Parks Canada. “It’s important that we say the words,” Young says, “but words are just the start. For reconciliation, we need to keep moving forward with actions.”

Read more from our Spring 2024 issue.