A revered and sacred art it is, the Japanese tea ceremony. The way of tea—or chado, in Japanese—is a practice of patience and a test of skill. Just outside Vancouver, Keith Snyder teaches the ceremonial form of chado, a discipline which he compares to martial arts or calligraphy. Frequent and consistent study is required to learn all facets and complexities of the ceremony. “You have to be very steady with the practice, and students tend to come and go,” says Snyder. “Their lives are so busy. It’s something you’ve got to stick with for a long time to even begin to master.” He practised his art while living in Japan for nine years, a very short period of time in which to learn, and now serves as resident tea instructor for the Urasenke Vancouver Branch, and as priest at the Tozenji Seizan Buddhist Studies and Cultural Centre in Coquitlam.

The Tradition

Urasenke is one of many schools that make up the great tea traditions of Japan. “Each distinct school descends from one tea master and is, in turn, carried on by certain families,” explains Snyder. “In the Samurai days, the tea ceremony was almost exclusively a men’s activity, but eventually men were in a position where it could no longer fit into their lifestyles. It was taken up by women, as were the arts of calligraphy and flower arrangement.” The lineage of Urasenke dates back to a 16th-century tea master, Sen no Rikyu, who is said to have perfected the art of chado. His book of seven rules still serves as the basic template to which all tea ceremonies abide, ensuring that each ceremony unfolds as one singular, exquisite moment for everybody involved. A true art, especially when sittings can be up to four hours long.

The Settings

Great tea masters from the 15th century onward were advocates of Zen, which explains the simple aesthetic ideals for which the Japanese tea ceremony is known—ironically achieved through an intricate set of rules. It begins with the removal of one’s shoes at the tea house entrance, and continues inside as guests are often greeted with a simple flower arrangement in the style of chabana. Rooted in the tradition ofikebana (the art of Japanese flower arrangement which follows a set of strict symbolism and line rules), chabana arrangements are specifically created for the spiritual ambience of the tea house. It encourages aesthetic guidelines, one of which suggests that flowers are placed as though they were in a field. “They should look quite artless, but it takes a lot of skill to do that,” says Snyder. The sparse blooms should face toward the guests, and it is not uncommon for the chabana to consist of just one perfect bloom.

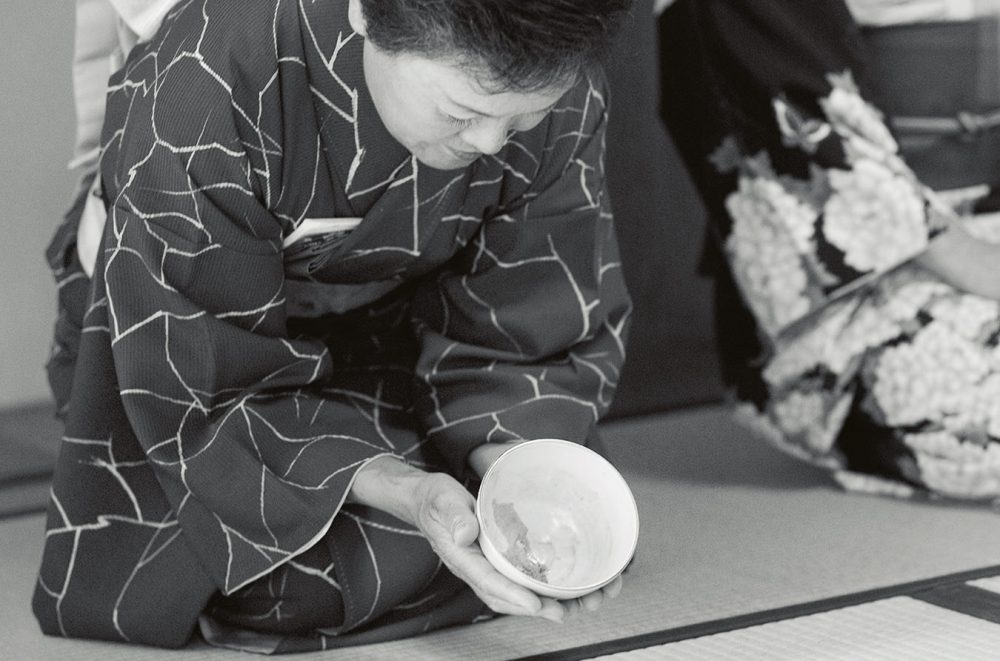

The Tools

A basic set of instruments is used in every tea ritual, including a cloth, matcha scoop, whisk, tea bowl, kettle and water jar. A ceremonial cleaning of tools in front of the guests reinforces the aura of a clear, fresh workspace, and the ladle smoothly transfers cold water from jar to kettle, to be heated over a hand-built fire. For these, Snyder uses kikuzumi charcoal, an extremely delicate charcoal that is so fine, it burns with absolutely no smoke (a necessity for any indoor ceremony). “When you see the ends of the charcoal burning, the patterns in the fire resemble chrysanthemums,” he says. The warm green tea is created in one communal tea bowl called a chawan, a larger vessel than a tea cup. When the matcha powder combines with hot water (never boiling) and a brisk whisking, the bowl is ready to make one complete circuit of the room for each guest to sip from, before it reaches its final resting place, empty.

The Tea

There’s no steeping involved when it comes to a traditional bowl of tea, and the bright green matcha comes ground in a fine powder, ready for whisking. Snyder describes the taste as slightly bitter and herbal, “with an underlying sweetness, but very fresh at the same time”. Depending on the ceremony, a thick or a thin version of tea is served—a long tea ceremony includes a serving of both, plus a meal, and a variety of sweets. A thin tea version generally plays out in about 50 separate steps, while the preparation of thick tea is slightly more involved. With no strict recipe to follow, the palate of the guest takes precedence over any formula. It should be an enjoyable experience for all; a notable change from ancient times when, as Snyder says, “it was considered more of a medicine and they called it a ‘dose of tea’.” Now, the Japanese tea ceremony is much more like a refreshing dose of meditation in our hurried world.

Photography by Tallulah.