Today, Henry Yorke Mann may live a quiet life on pastoral land outside Oliver, British Columbia, but his legacy reaches right across the province from the Interior to the Lower Mainland to Howe Sound and beyond. Alongside architects Ron Thom, Arthur Erickson, Bud Wood, and Fred Hollingsworth, Mann was at the forefront of an architectural style that became known as West Coast Modernism. So familiar is the aesthetic, with its cedar post and beam construction, that it has become the norm to people who grew up on the West Coast.

However important Mann’s contributions were to this movement—which in turn has defined the architectural heritage of our region—the architect came upon his career, quite literally, by accident. In the 1940s, Mann attended Washington State University on a ski scholarship, where he had his sights set on qualifying for the 1952 Olympic Winter Games. When cruising through a ski course at over 100 kilometres an hour, Mann crashed, and ended up with a double hernia. The injury caused him to miss a year of training, removing him from competition. Despite his misfortune, Mann decided to pursue his other interest, architecture, at the University of Oregon.

After school, Mann returned to Canada. He went on to work for Mercer and Mercer Architects, where he stirred up some attention for his modernist design of the Killarney Community Centre in Vancouver. (The building has since been renovated many times.) It was the 1950s and ‘60s, and Mann remembers, “It was a great time, filled with be-ins, jazz and folk music. Most of my friends were architects, artists and writers.” Mann and the other architects—who ultimately became known in varying degrees for their work—were young and ambitious.

“There were people coming out of what they called the Prairie School, and Arthur, Bud, Fred, and myself were the ‘West Coast’ school, as such. I didn’t see it as a school of thought at that time, but looking back on it, you could reasonably say so.” The movement, which celebrated nature and functionality, was taking shape. “And Arthur Erickson, he was a visionary—an incredible thinker.” Mann adds, “He could explain things better than anybody I’ve ever seen in terms of his work. He actually sponsored me for my Canada Council grant at one time.”

Mann was equally influenced by his father and grandfather, both master builders, and through them, he inherited a love affair with wood, because it is sustainable, a natural insulator and, quite simply, beautiful. One of Mann’s earlier creations was the Engineers Club that once stood on Hornby Street. It was built in 1964 and its interior was lined with narrow slats of wood, both vertically and horizontally. Judging by photos, it was truly an inner sanctum. It was followed by a series of houses that consistently maximized natural light, used natural materials, and considered the shape and size of structure in relation to the land it occupied.

In 1969, Mann chose to leave architecture to become a rancher, first in the Squamish River Valley, then on 700 acres of land near Oliver, where he had 500 head of cattle. It wasn’t until around 1993, when he was in his 60s, that he decided to return to architecture, as if he’d never left the profession.

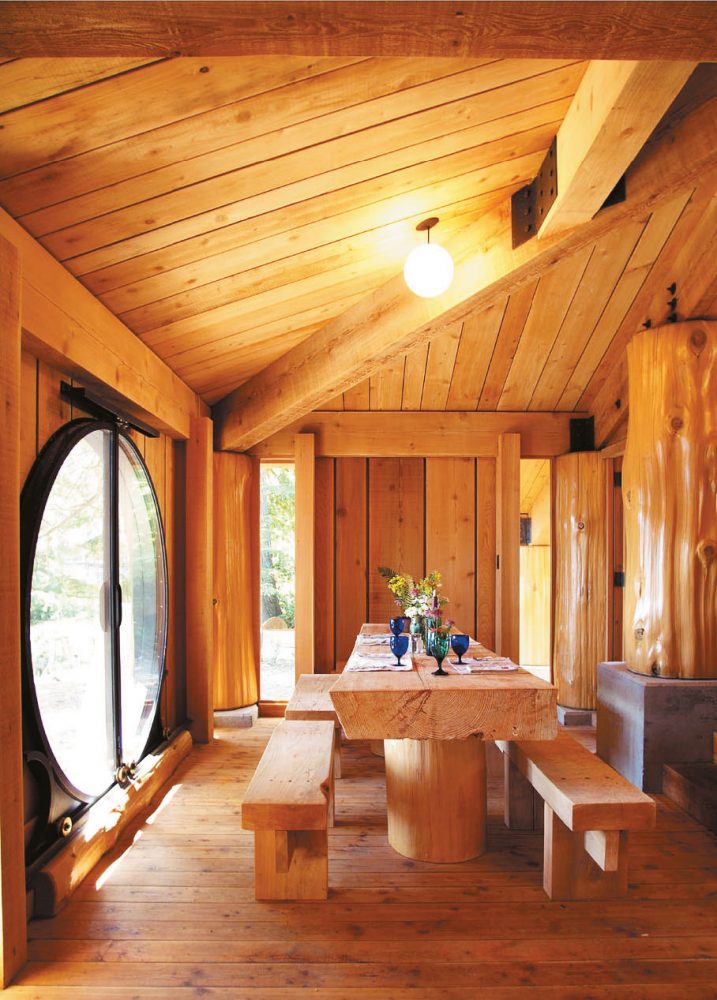

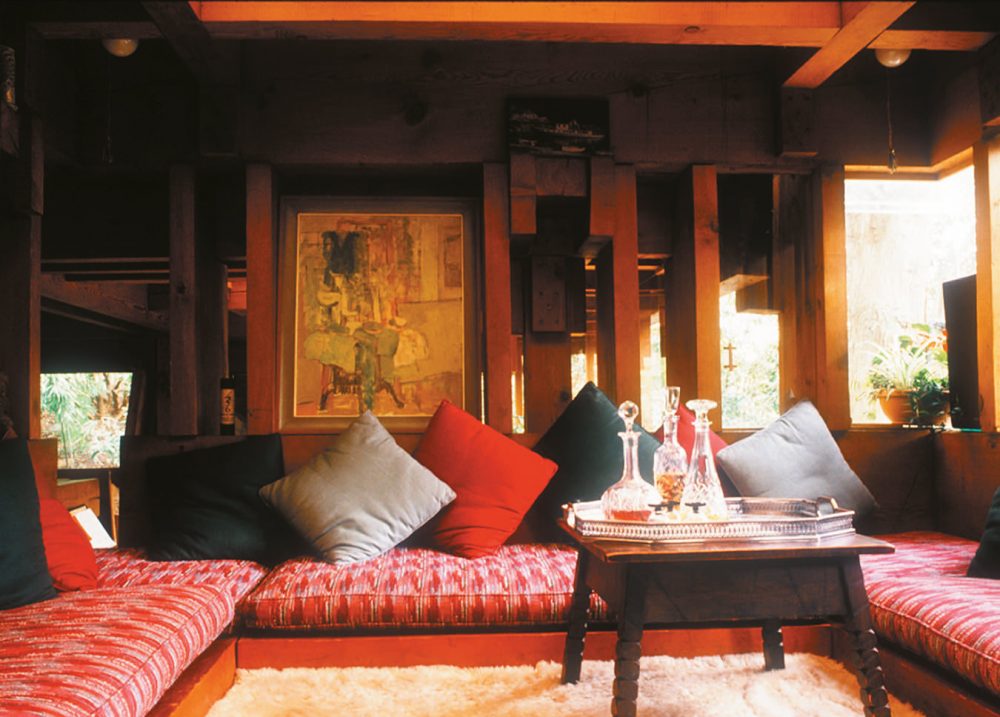

His latest residential designs, such as the Japanese and First Nations longhouse-inspired Posts Standing residence on Gambier Island, are equally impressive, so defined is his vision. Posts Standing is a symphony of timber built from second-growth cedars that came directly from the 1.25-acre lot. Owner Bruce Ramus, who collaborated on the design, recalls Mann’s 35 pages of “beautifully hand-drawn” illustrations, complete with details such as brackets and bolts that keep the exposed timber posts and four-inch-thick cedar walls anchored to the foundation. It took two years and $500,000 to build, and now, the home is for sale with Sotheby’s for $1.5-million.

As for why Mann, who, at 80, continues to work today, returned to his profession at a time when most people were retiring, he says, simply, “It was time.” Arthur Erickson, he adds, also explained it well. “They interviewed Arthur on CBC one time, and he has all these accolades and he’s famous, and the interviewer said, ‘Why do you keep on working?’ [Erickson] said, ‘Because I need to.’ I think that’s the best answer. People can read into it however they want.”