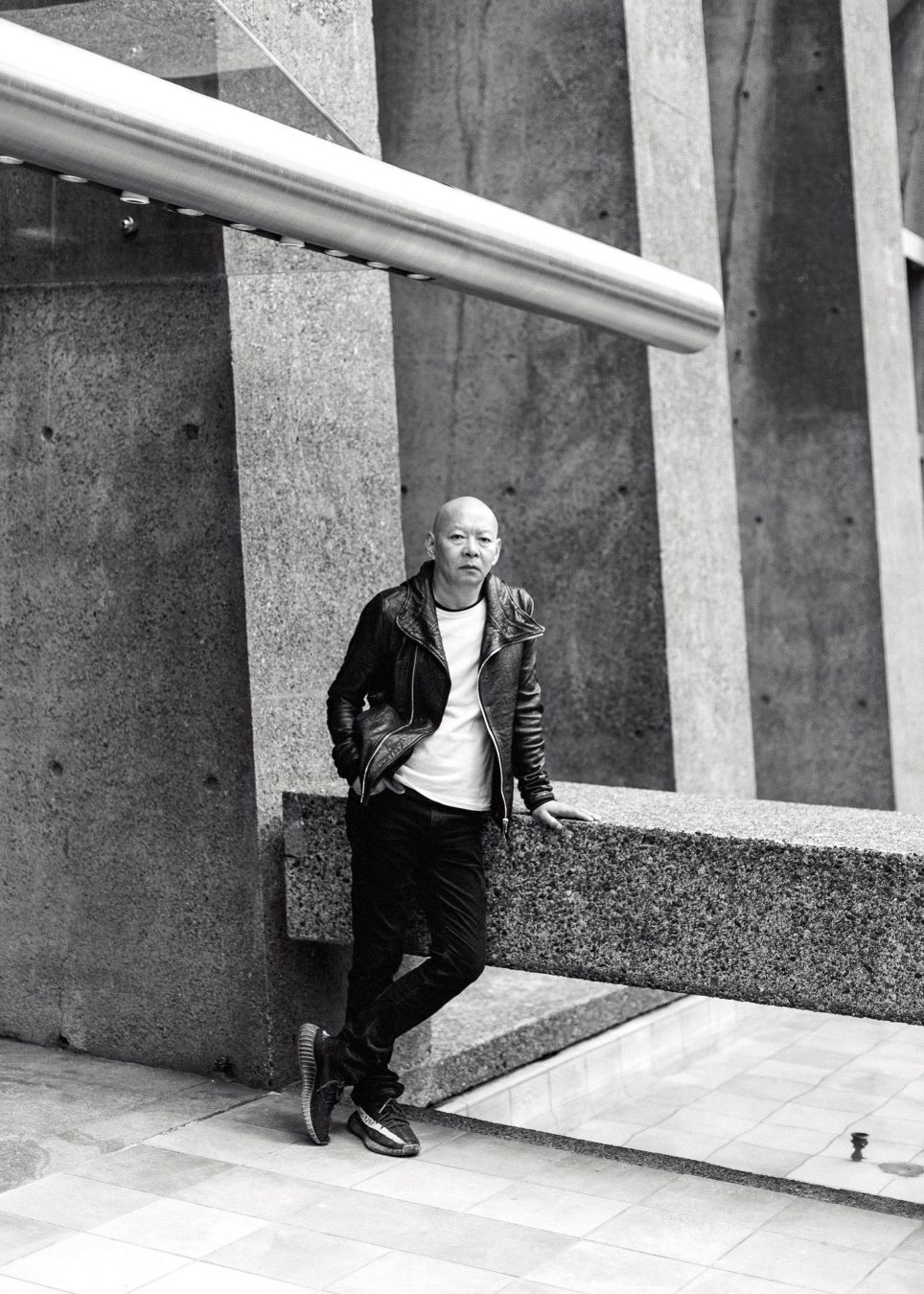

“It is me, yes,” he says. “But I don’t think of my creations as mimetic, so is it really me? I doubt that.” It is a fascinating conundrum of sorts, in which a self-portrait becomes something larger than the person, the artist. It is not unlike Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, the mischievous inclusion of self-portrait elements causing all kinds of ripples of possible meanings, and even controversy. Minjun is aware of the effects his works have had, but says, “I do not create art for the sake of an audience. Not at all. It is for the sake of the art itself.” He is a quiet, thoughtful, but precise person, and he adds, “I begin with an idea, a concept. Sometimes it goes well, and I reach completion of the work, and it is what I envisioned. Many times, however, I must stop the process, because I can see it has gone wrong. I must then begin again.”

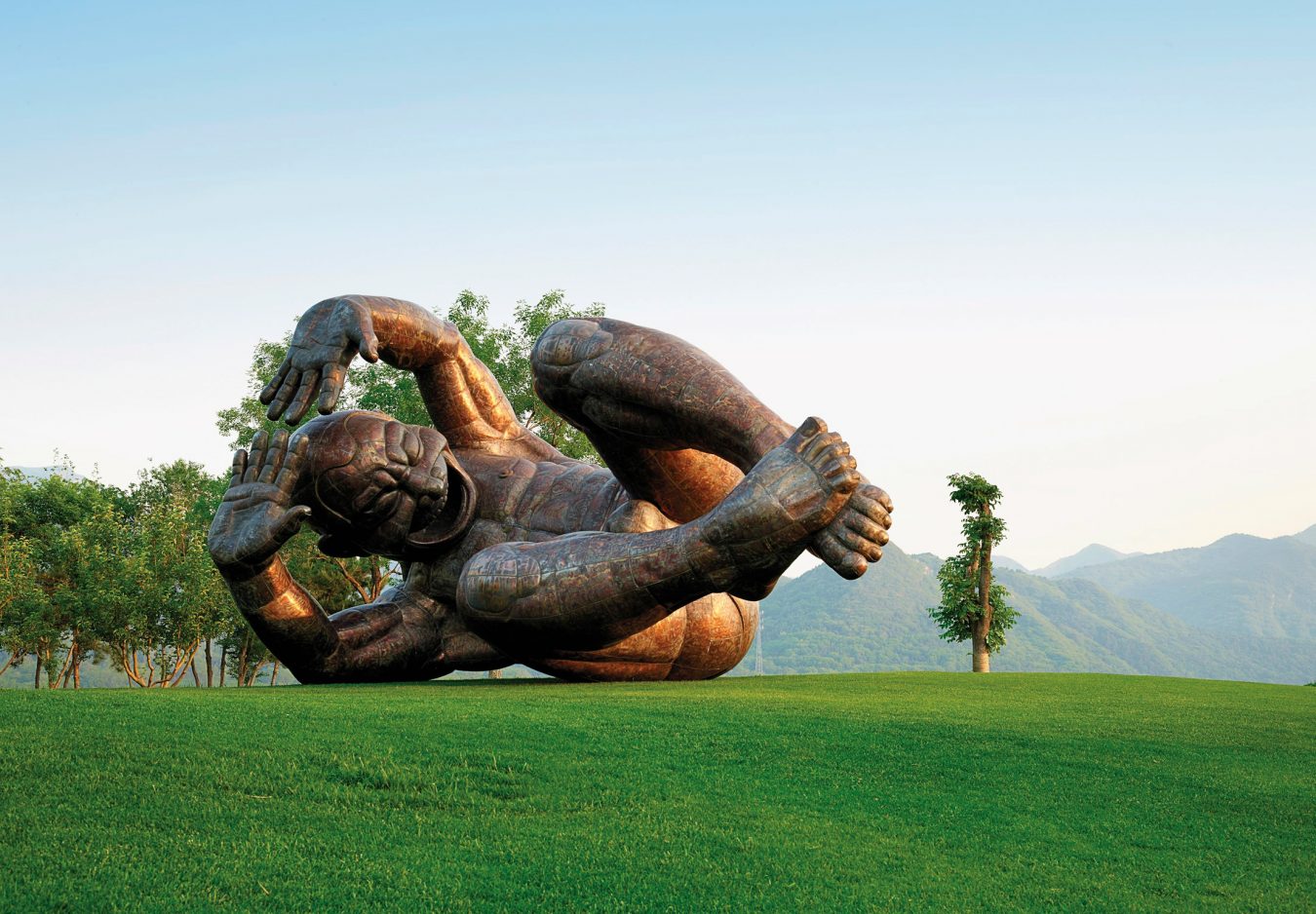

弯曲的维度, flexible dimension, L 7.8m x W4.5m x H4.3m.

With some of his paintings reaching well over the five-million-dollar mark, it is safe to say Minjun’s vision seems to be fully realized more often than not, and that an appreciative audience exists, international in its scope. He decided one day to “try the laughing man in three dimensions, to see what that would be.” Part of that project became the famed 14 figures in English Bay, which drew immediate, enthusiastic responses from the people who thronged to see them and interact with them. The installation, part of the Vancouver Biennale’s ongoing, steadfast commitment to bringing world-class public art to the city, was scheduled to reside here for two years, with the hopes of raising enough interest and funds to keep it here permanently. The multi-million-dollar price tag was proving a serious impediment to that plan, but, according to Biennale founder and president Barrie Mowatt, “the artist was a bit surprised, I think, but also moved, when we informed him of how much his works were engaging the people here. So he dropped the price to a very low $1.5 million.”

At that point, Shannon and Chip Wilson joined the fray, purchasing and then gifting the sculptures to the city. Thus, A-maze-ing Laughter has a permanent home near the beach. Minjun is still impressed, years later, with how popular his work is. “I saw photos and videos of people interacting with my sculptures, enjoying them. This is not something I anticipated, but it is gratifying,” he says. “My art is certainly meant to elicit a response. I cannot, and do not want to, control that response. This is very important. The art must speak for itself, and each person has their own way of understanding it.” The interpreter keeps up with Minjun easily, because he speaks so concisely, patiently, answering questions he has perhaps heard more than a few times. But every so often she must ask Minjun for clarification, which he provides. Through this process, he will not usually string together a lengthy sequence of sentences, but rather keep things short. The result is answers that he considers for quite a few seconds, taking in the question fully, and answering similarly.

“Yes, I want my work to affect the world. To create thought and feeling more than anything. But I never think about how the world will respond to me. I do not work for approval.”

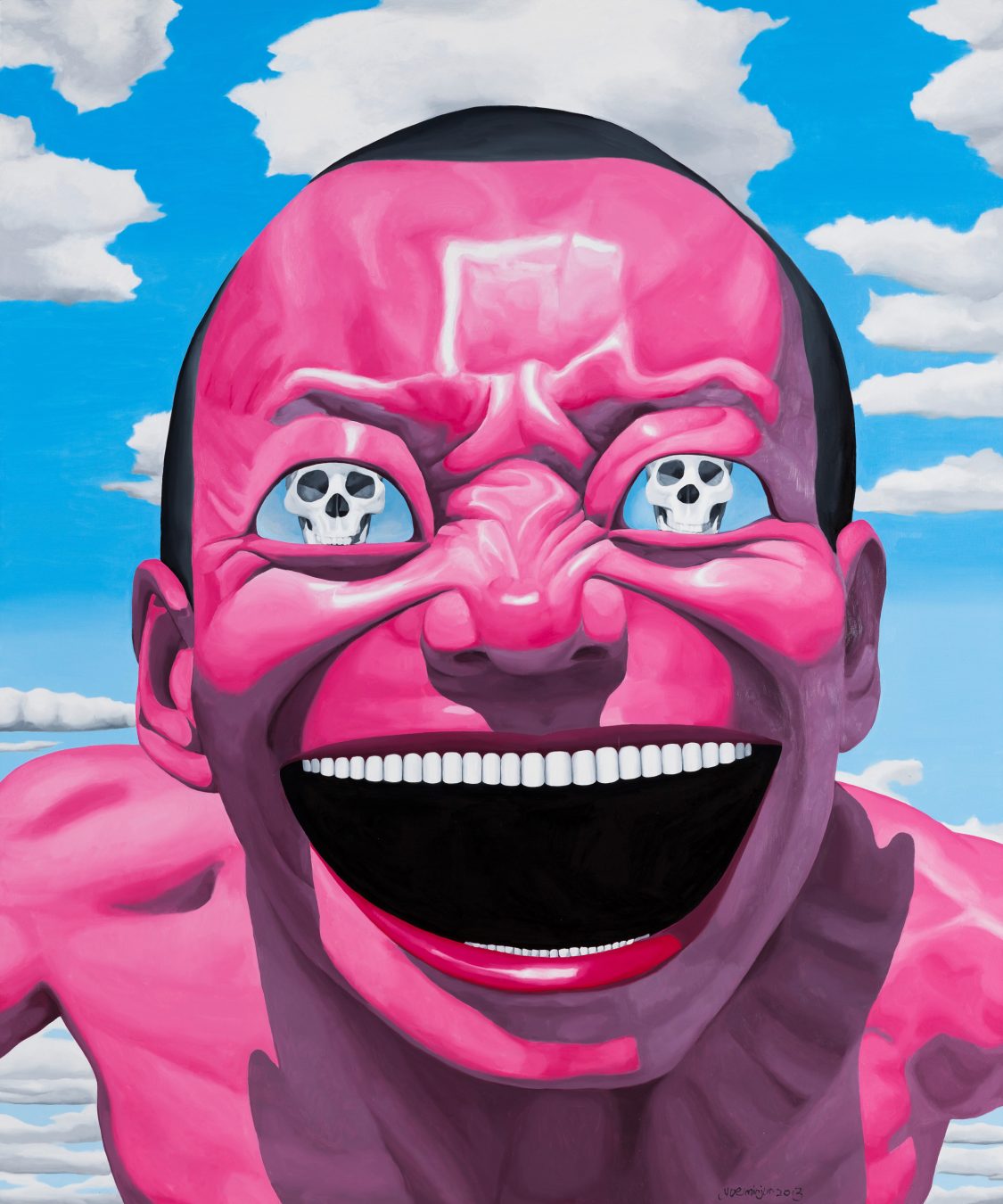

Many of Minjun’s most famous works have those smiling faces we see in English Bay, but they are not, of course, always in the same context. For example, in The Execution, four smiling men are facing what looks in every way like a firing squad, except the executioners are not actually holding weapons. And Isolated Island shows three smiling figures, in their familiar, lurid pink skins, but with their hair coiffed to show devil’s horns. The effect, generally speaking, is of a mildly hysterical response to something momentously awful, threatening, intimidating. Clearly, the artist knows exactly what he wants to say in these works.

孤岛Isolated Island_布面油画_300 x 300cm, 2010.

Minjun has been associated, by press and art critics around the world, as part of a post-Tiananmen Square movement called “cynical realism,” but he basically calls it off while in no way denying the movement itself. “Obviously in my country there are problems. How does an individual react to the world? That is a good question,” he says. “And then how does a person take any kind of action? Another good question. But I do not think of myself as part of a large movement. We are artists trying to express something, to express ourselves, our view of the world.”

Minjun sits back, easily, in his chair. He looks around the expansive lobby, looks at his interpreter and at the Biennale founder, and, remarkably, says, “Yes, I want my work to affect the world. To create thought and feeling more than anything. But I never think about how the world will respond to me. I do not work for approval. To me, art is not an affirmation, and not condemnation. It is a questioning.” Mijun’s manner is not quite formal, but he is quick, smart, and not at all reticent about art. “Life is sad,” he says, “and we can only face it by deflecting it.” In a way, that acutely explains the laughing men: everything about the paintings, and the sculptures, suggests shock, dread, exposure, and helplessness—but all with that gaping, shouting smile or laugh, which suggests, after all, that at least we try.

There are virtually endless possibilities for Minjun. The laughing face can be seen wearing an astronaut’s helmet, or, in Floating, as several disembodied heads suspended in the sky, interspersed with human skulls. Often lurid, even macabre, the effect is at once startling, challenging, and beautiful. It is a potent recipe for self-expression.

As he prepares to leave the hotel, to get on with his day, in which he is scheduled to meet the public at the site of his sculptures, Minjun finishes his coffee and cordially expresses his gratitude. One just cannot help but wonder what work of art he is working on in his mind, as he wends his way through his days in Vancouver.

From the Archives: This story was originally published on January 8, 2018. Read more stories about the arts.