Geena Wilson reaches into a file drawer, pulls out a photograph glued to cardboard, and places it carefully face down beneath the lid of a scanner. Bright light seeps from beneath the lid as a mechanical hum fills her workspace, a shared cubicle in a windowless room at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria.

Geena Wilson reaches into a file drawer, pulls out a photograph glued to cardboard, and places it carefully face down beneath the lid of a scanner. Bright light seeps from beneath the lid as a mechanical hum fills her workspace, a shared cubicle in a windowless room at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria.The photograph—a landscape of a cemetery in Alert Bay—is the 13,694th photo she has converted into an electronic image. She has been doing this for 16 months; there are 9,000 images still to go.

The young data technician could not be happier spending her workday on so painstaking a task. Wilson maintains a cheery perspective on the mountain of work she faces. “It was daunting when I first started,” says the University of Victoria graduate in anthropology, noting how her interest was sparked by having First Nations friends growing up in Port Hardy on northern Vancouver Island. Her daily goal is to process at least 50 images, a task so important, she says, “there are backups of backups.”

A woman drying salmon (image PN6103). Courtesy of the Royal BC Museum.

Many of the original photographs were taken in the 19th century, when earliest contact between First Nations and colonists was still within living memory. The equipment at the time demanded long exposures, bringing to a halt human activity to pose for the camera. All these decades later, we are left with tableaux of silent beauty—a still cemetery, a longhouse with carved entrance poles, a man standing erect next to a totem pole as tall as a young cedar. One of the images Wilson has pinned to her cubby depicts a laughing child with a dog, likely taken around the time the Songhees reserve was forced from the nearby Inner Harbour to its current location to the west. Even so joyful an image comes with a sorrowful tale.

The process of digitization may appear tedious, but it brings history to life. The museum is now able to make its ethnographic visual and sound recordings available to people around the globe. Most importantly, the project makes the items accessible to families and communities in B.C. for whom such records are most valuable. It takes a respectful approach to the task, consulting with elders and nations on the depiction of such ceremonies as potlatches and funerals. Their knowledge adds to what can be learned about the past.

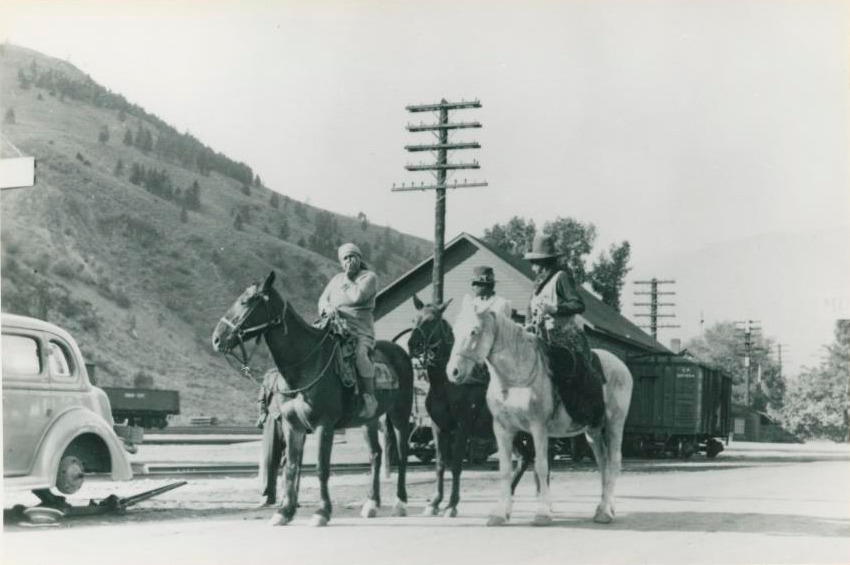

Paul Brenson, Jack D., Willie Beynon, (?) Fluen, Ernest D. on Annie Louise, circa 1932 (image PN22354). Courtesy of the Royal BC Museum.

“This digitization is long overdue,” says Lucy Bell, the museum’s head of Indigenous collections and repatriation. “In the past, Indigenous people would have to get to Victoria, book an appointment, and look at the materials.” Bell has witnessed remarkable scenes of family members identifying ancestors by name in decades-old images long unseen.

“It’s important for people to see their history, their ancestors, their buildings,” says Bell, who joined the museum two years ago after being at the forefront of the Haida Nation’s repatriation program. One of her own relatives, a master carver, has consulted the images to better design a traditional canoe. The photos offer a rich trove of historical detail for poles, hats, sweaters, blankets, baskets, rattles, spears, drying racks, longhouses, and all manner of the minutiae of daily life perhaps otherwise lost to the ages.

An unknown location likely in the B.C. Interior (image PN15331). Courtesy of the Royal BC Museum.

She expects these images to be displayed at conferences, made available at community cultural centres, or used in language schools throughout the province. An object as small and ordinary as a memory stick makes it easy to return images to the geographical place where they were first captured.

There have also been 489 recordings of First Nations audio tapes that have been digitized. These include language lessons and intensive biographical interviews. The digitization project is being sponsored by FortisBC, which contributed $30,000. The utility, which distributes electricity and natural gas, adopted the project as an “initiative that has a really tangible impact,” says Carmen Driechel, FortisBC’s community and Indigenous relations manager. The donation helped cover the cost of software, a scanner, and the hiring on contract of a technician. Elsewhere on Vancouver Island in 2019, FortisBC has helped finance a drum-building program for youth in the Scia’new First Nation. And for the Stz’uminus First Nation’s Nutsumaat Syaays project, a transmission crew used a crane truck to safely move a massive welcome figure from carver John Marston’s workshop to Ladysmith Secondary School, in addition to the utility’s financial support for the project. It’s all part of FortisBC’s ambition to provide meaningful benefits to the communities it services.

A view of the village of Bella Coola, circa 1873 (image PN7195-B). Photo by R. Maynard/Courtesy of the Royal BC Museum.

Back at the museum, there is a sad recognition of the knowledge lost when photographers failed to identify their human subjects.

“Maybe it was their inability to spell Indigenous names,” Bell says, “or maybe they just didn’t believe it would be of value.” How wrong they were. Some recent Tsilhqot’in visitors were astonished to see an image of unnamed teenage girls from their community, and were eager for others back home to be able to peruse the digitized archive. Photo by photo, tape reel by tape reel, lost moments in time will be relived by relatives and ancestors eager to know more about those who came before.

To view the Royal BC Museum‘s Indigenous digital archives, click here and type “pn” into the Catalogue Number field, then click search. You can also search by culture (such as Haida) or a specific community.

Discover more people and organizations making an Impact.