Excerpted from From Louis to Vuitton, published by Assouline.

In the 15th century, hoping to find a shorter route than Marco Polo’s to reach China and Japan, Christopher Columbus went off course by 10,000 kilometres and accidentally reached the American continent. That is called serendipity—to unexpectedly and unintentionally make an important discovery. The genesis of the most legendary modern motif was also the result of a marvellous instance of serendipity, combined with business rivalry and a touching tribute. History’s most famous trunk-maker died on February 27, 1892, leaving his heir to carry on this enchanted adventure. But Georges’s first challenge was to protect the Maison his father had founded from counterfeiters.

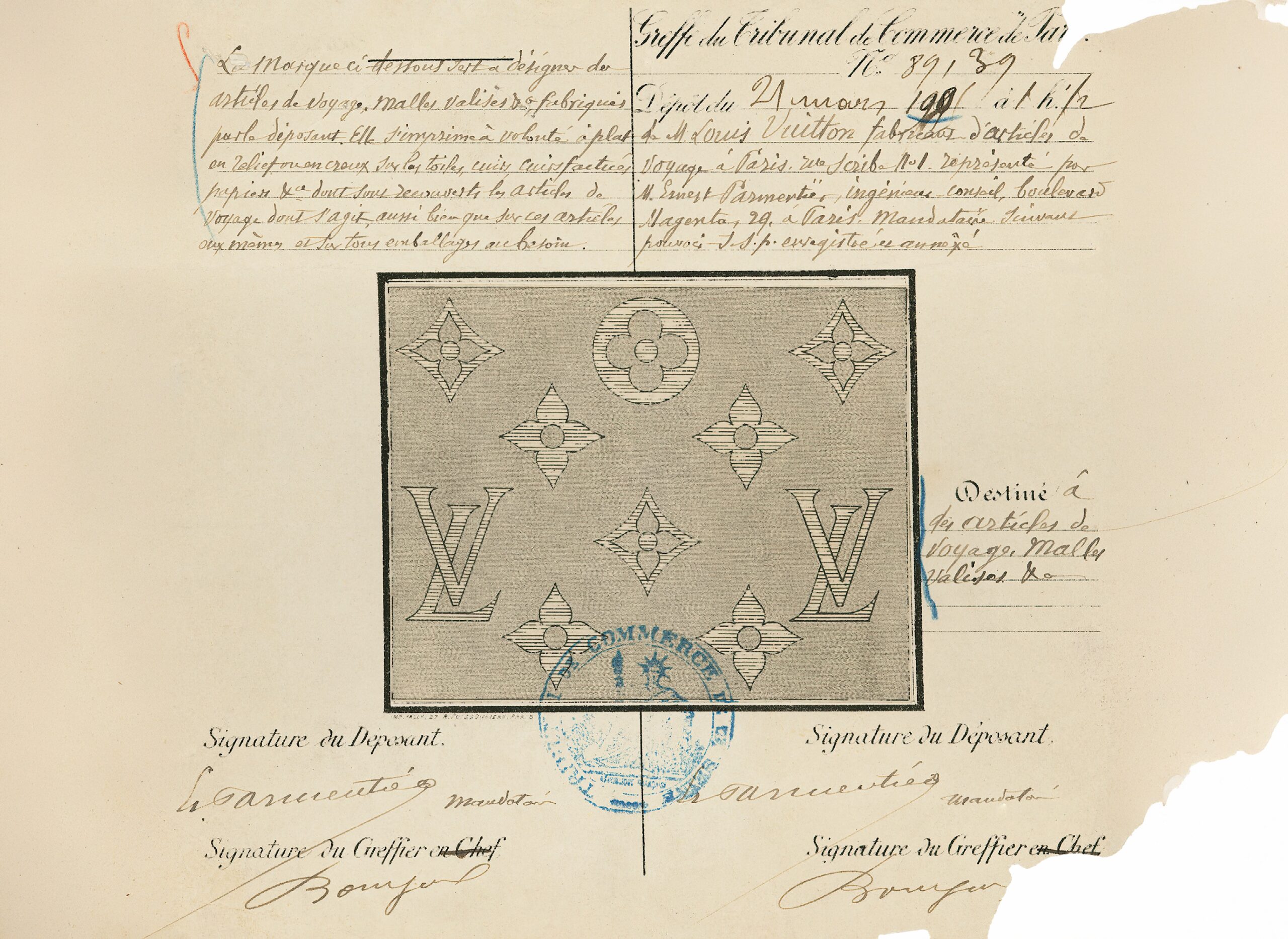

As it happened, Louis Vuitton trunks were an immediate success due to their innovative structure and meticulous craftsmanship. Thanks to the coated canvas’s impermeability, trunks could now have flat lids, and although they were aesthetically distinctive, they were immediately copied. Over time, the Maison would create different motifs to set itself apart from the competition. But the Gris Trianon canvas (1854) was too easy to imitate. The Rayée canvas, in alternating red and beige (1872) or beige and brown stripes (1876), could still be duplicated. The Damier canvas (1888) seemed more secure with “Marque L. Vuitton déposée” or “L. Vuitton Marque de fabrique déposée” appearing on certain squares of the mesh pattern. But the Damier, or checkered, pattern was a classic motif, often used by other trunk-makers, and one needed very strong glasses to make out the small inscription. The years went by, Louis passed away—and then Georges had a brilliant idea.

A (Oedipal) rumour has it that the son may have considered using his own initials before acknowledging the obvious choice: to associate, by honouring the memory of his father, the articles manufactured in Asnières with an immediately recognizable signature, one so specific that it could not be copied. In other words, a motif which could belong only to Maison Louis Vuitton, and better yet, which defined it. In 1896, after many weeks of reflection, Georges drew the logo himself and created the LV canvas. It was rebaptized “toile Monogram” in 1985. Initially made of linen jacquard in beige and brown—the colours of the Damier canvas—the motif was stencilled in 1902, then released in several colours until the 1930s, when it appeared on Vuittonite, the waterproof cotton canvas. In the official trademark application dated 1905, Georges explained that his design “can easily be printed on flat, curved, or hollow canvas, leather, imitation-leather, paper, etc., with which travel goods are covered.”

What was the source of this extraordinary imagination? According to the dictionary, the word “monogram” dates to the 16th century and derives from the late-Latin monogramma, composed of the Greek mono (single) and gramme (letter). It describes the mutation of several letters (often the initials of a name) into a single figure through a graphic intertwining. But the Monogram canvas features more than just the paternal initials: it also includes three alternating geometric flowers whose design has intrigued historians—but whose secret was known only to Georges. One fact is certain: Louis’s son loved fashion and knew a great deal about art. Interestingly, many of his fellow designers at the time were influenced by two major movements: art nouveau, inspired by nature and japonisme, and neo-medievalism, inspired by an idealized view of the Middle Ages. Indeed, these seem a more likely inspiration than the Gien earthenware tiles in the Asnières residence’s kitchen which have often (and rather hastily) been linked to the spiritual birth of the Monogram.

Louis Vuitton Jeune (2015), a painting by Chinese artist Yan Pei-Ming, a portrait created especially for the exhibition Volez, Voguez, Voyagez (Grand Palais, Paris, 2015-16), based on a photograph of Louis Vuitton by Reutlinger made around 1892. Photo ® © Stéphane Muratet, Louis Vuitton Malletier – Steve Harries/Collection Louis Vuitton, 2015. “Louis Vuitton Jeune” – Yan Pei-Ming. Photo courtesy of Louis Vuitton.

Another time-related coincidence: In 1857, the year Georges was born, Viollet-le-Duc was in charge of the restoration of Notre-Dame Cathedral, and Louis’s son was a known admirer of the extraordinary architect. In the literary domain, Victor Hugo, who dominated French literature for half a century, idealized the Middle Ages. All these indices led to the twinning of the Monogram flowers with the Gothic rose window and the trefoil and quatrefoil ornamental details framing Notre-Dame’s stained-glass windows. Lastly, we know that Georges and later Gaston-Louis were passionate about heraldry, the ancient art of blazons and coats of arms. Abracadabra! The miracle happened: the fusion of past and present into a semi-organic, semi-geometric motif, with a universal appeal which would change the course of history.

Therefore, the Monogram can also be considered as the first logo of our era. Of course, before Louis Vuitton, artisans signed their work with a stamp or a label. But with Georges’s invention, the trunk-maker became the first house to inscribe a name other than that of the client on a piece of luggage—and to reproduce it endlessly. Would such unwitting audacity have been shocking at the time? Probably. It not only took the counterfeiters by surprise—copying a checkered pattern is one thing, but who would copy the initials of a competitor?—but also gave the Maison an incomparable symbol of exclusivity. The expansion of the family residence in Asnières, undertaken in 1900, as well as the construction of the Vuitton Building on the Champs-Élysées in 1914, demonstrated that the trunk-maker had, in just a few years, substantially grown in stature. In the eyes of the public, the artisan was not just making high-quality articles but creating treasures, which in turn made their owners feel as if they belonged to a very exclusive and enviable society. The concept of modern luxury was born.

And that modern luxury, driven by the aura of the legendary motif, would reach new heights. In 1959, the development of a soft, resilient, and versatile canvas provided the Monogram with endless possibilities. The Monogram had become motif as well as material—like Rodin’s marble—and the most thrilling artists and artisans of the time chiselled their creations based on the graphic icon. Each trade adapted it to its own purpose—from diamonds to chocolate—and each continent appropriated it for a specific reason. The popularity of the Monogram in Japan, for example, can be attributed to the mon and kamon, the geometric pictograms which symbolize samurai culture. Which reminds us that Georges was inspired by art nouveau, itself inspired by japonisme. The history of the Monogram is a magical loop. Jeff Koons, known for self-aggrandizement, pushed this idea to the extreme in his 2017 Masters Collection by combining his own initials with those of Louis Vuitton on the very same canvas!

No discussion would be complete without speaking of the prophetic Marc Jacobs. When he was appointed artistic director of the Maison in 1997, the designer faced the colossal challenge of propelling the Monogram, that noble and now older demoiselle, into the new millennium. His revolutionary collaborations required audacity along with a powerful vision. “Stephen Sprouse’s graffiti on the Monogram canvas,” recalls the designer, “seemed to distort something, when in fact it drew attention in a new way, especially from young people, to this motif, which was such a classic. It was disrespectful and respectful at the same time. And I think that is why it worked.” A second revolution occurred in 2003: Takashi Murakami reminded us of the motif’s magic when brought to life in colour, with the Monogram Multicolore and the Eye Love Monogram.

The waltz would never end. In 2015, Nicolas Ghesquière reinvented the red Monogram canvas and, season after season, renewed the iconic design with prodigious energy. Kim Jones, Virgil Abloh, Pharrell Williams. In velvet, satin, denim, leather, in Mini and Oversize versions, in Monogramouflage and Reverse. The Maison’s creative directors would unveil, collection after collection, their increasingly sublime and unexpected interpretations of the Asnières trunk-maker’s coat of arms. An optical signature which has become as emblematic of fashion and leather goods as the Eiffel Tower is of Paris. One wonders if Mendeleev, when completing his periodic table of the chemical elements which compose all known and unknown matter on this planet (“Au” for gold, “Ag” for silver…), might have forgotten the last: LV for Louis Vuitton.

Read more from our Winter 2025 issue.