In the mid-1960s, Lamborghini changed the game when it introduced the low, lean, and gorgeous Miura P400. Powered by a mid-mounted V12, it drew a line in the sand: on one side, ordinary cars; on the other, supercars. There had been fast cars before, but the Miura was something different: the establishment of an automotive nobility.

It was, of course, very expensive, an experience reserved for those who are themselves of noble rank or at least well-marbled wallet. But as the 1960s drew to a close, an unlikely steed appeared to challenge the superiority of the rampant bull of Sant’Agata Bolognese. It had half the wheels, one-third the cylinders, and hailed from Japan—not a place then known for the production of luxury goods. It was the 1969 Honda CB750, the world’s first superbike, and unlike the Miura, it would lead to the creation of an entire democracy of performance.

Today, a Miura is a blue-chip collectible firmly in the seven-figure range. The CB750 is not. Honda sold roughly 400,000 of these motorcycles in its first decade and still sells one new. It currently costs $11,625, which includes freight charges.

You can find used Honda 750s for less than half that amount, from vintage 1970s project bikes to collector-plated V45 Interceptors. So successful was this bike that it provoked a sort of arms race among Japanese motorcycle manufacturers that led to the creation of the informal term “UJM” for Universal Japanese Motorcycle. Honda was first, but it kicked off a wave of powerful, reliable, and very quick machines from across the Pacific.

How quick? In 1969, Honda claimed the CB750 would clip through a quarter-mile drag race in 13.4 seconds with a top speed of 201 kilometres per hour. The improved-for-1969 Miura P400 S? A second slower. Given enough road, the Lamborghini would catch and surpass the little Honda, as it had a higher top speed, but dollar for dollar, the CB750 was unmatched.

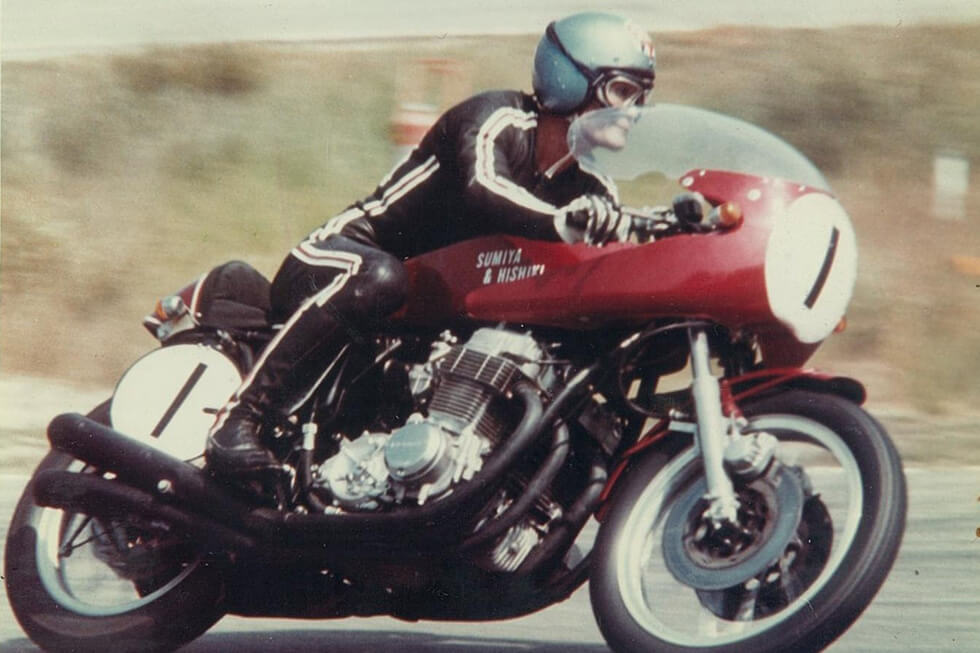

Italian motorcycle builders like Moto Guzzi or Ducati would have been unsurprised to see this kind of performance from a Honda product. Both had already been racing against Honda teams for years and knew that Japanese bikes were tough to beat. At the time of launch of the CB750, Honda was sitting on six consecutive years of winning the world Grand Prix title in the 350cc class, as well as dominating in the 250cc class.

The latter were especially crazy. In 1966, the Honda RC166 won all 10 250cc class races, pumping out 60 horsepower from a tiny inline-six engine that spun to a hummingbird-heartbeat 18,000 r.p.m. peak. It was almost more jewel than motorcycle, and its delicacy was only matched by its relentless speed.

At the same time, Honda was participating in Formula One, even though the company had scarcely built its first production car. The F1 racers weren’t quite as successful as Honda’s motorcycles, as the chassis technology was a step or two behind the competition, but the small displacement V12s were mighty. At the Mexico Grand Prix, which favoured greater power, Honda was able to secure its first outright F1 win.

Translating this performance to the street wasn’t so easy. In the mid-1960s, some motorcycle dealers in Canada began importing the S600, a toylike two-seater roadster sized to make an original Miata look like a Cadillac. Crammed with motorcycle technology, including chain-driven rear-wheels, its 600cc four-cylinder engine spun to a frothy 9,500 r.p.m. Certainly exhilarating, but really more suited to narrow Japanese mountain roads than across Saskatchewan in February.

The situation was similar when it came to motorcycles. Honda was already the largest motorcycle manufacturer by the 1960s, thanks to the success of friendly little bikes such as the SuperCub. These had entirely changed the postwar image of motorcycling from a leather-clad Marlon Brando in The Wild One to The Beach Boys singing “It’s more fun than a barrel of monkeys” in “Little Honda.”

Honda’s high-performance road bike at around this time was the CB450, which had a two-cylinder 450cc engine with twin overhead camshafts. This could outperform larger displacement bikes from British manufacturers such as Triumph, but North American buyers were lukewarm to it. Just as some buyers chose V8 engines in their passenger cars for torque, others wanted a bike with grunt.

They got it.

There had been fast motorcycles before the CB750, but these were generally very expensive and occasionally bizarre. The Vincent Black Shadow, for instance, launched in 1948 as the fastest production motorcycle in the world, had a top speed of 125 m.p.h. That’s scarcely slower than the Honda, but these were handmade, labour-intensive machines, and fewer than 1,800 were built over seven years.

Honda was soon making well over that number of CB750s every month. Priced at close to half what you’d pay for a Triumph 750, and making a little more power than a 1300cc Harley-Davidson, the Honda was flying out of showrooms.

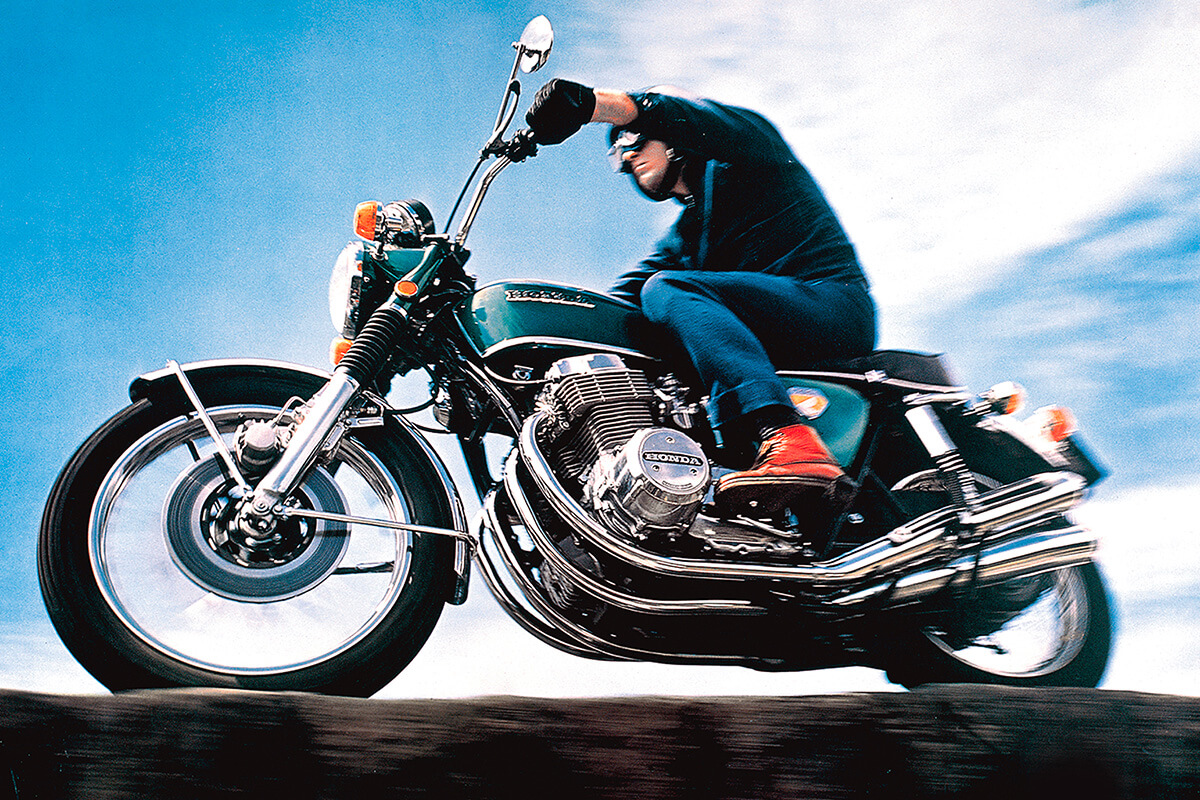

It helped that it was gorgeous. Modern motorcycles are often festooned with cheap-looking plastic parts, but the original CB750 had lashings of chrome, four individual exhausts, and brightly painted or polished metal parts.

The motorcycle’s 736cc (to be precise) four-cylinder engine revved to a redline of 8,500 r.p.m, significantly lower than the smaller Honda CB350 also in showrooms. It was less frenetic, more capable of loafing around 2,000-3,000 r.p.m, then hauling up to highway speeds. When slowing back down again, the front hydraulically operated disc brake was a significant safety and performance improvement over the cable brakes found elsewhere.

Period reviews struggled to find fault, with Cycleworld calling it “the finest handling machine in its weight class” and pointing out that tires might wear out a bit faster than usual because it goes through corners so quickly. In terms of impact, it was the company’s Honda Civic moment, if every Honda Civic had been as fast as the Type-R currently is.

Honda produced tens of thousands of these motorcycles right through the 1970s. In the 1980s, the likes of the 750 Nighthawk carried forward most of the original spirit of the bike, and 750cc displacement Honda motorcycles were built right into the 2000s. However, by 2010, even larger displacement bikes had taken up the torch. The Honda CB1100—with, you guessed it, an 1,100cc displacement—was seen as the spiritual descendant of the original CB750 up until it stopped selling in 2022.

The current CB750, called the Hornet, is a very different beast than its distant ancestor. Not powered by a four-cylinder engine, it instead has a 755cc parallel-twin engine, one that makes a little over 80 horsepower at 8,500 r.p.m. For what is now considered a middleweight bike, it’s got grunt and a pleasing growl as the revs come up.

Even better is just how friendly it is. The magic of the original 750 is that it packaged a great deal of performance into a bike that was easy to ride and even easier to live with. The Hornet manages the same trick, with an upright riding position, broad powerband, and a host of aids to make riding easier.

If you want more, Honda will sell you that too, with the CB1000 Hornet SP. But you don’t really need more power. The dream of the original CB750 was never about causing a commotion. The magic is that, for thousands of riders, it provided easy access to a bigger barrel of monkeys.

Read more transportation stories.