Stomping fluffy snow off my down-filled winter boots, I step into the four-person Banff Gondola cabin and take a seat. On the climb through the darkness, blue mood lights illuminate the interior, and soulful spoken words and music replace the hum of cables pulling us up the mountain.

“Tonight, we honour these mountains and those who have called them home since time immemorial,” floats from a speaker inside the gondola cabin, introducing the Stoney Nakoda Nation, Indigenous peoples who call the Canadian Rockies home.

The eight-minute gondola ride up Sulphur Mountain sets the stage for Nightrise, but it’s not prescriptive. Instead, we are invited to let our senses guide us, to look (Akida), listen (Anârhoptâ), lounge (Skâs îgam), and repeat (Akes yo ta), to create a sense of anticipation and discovery.

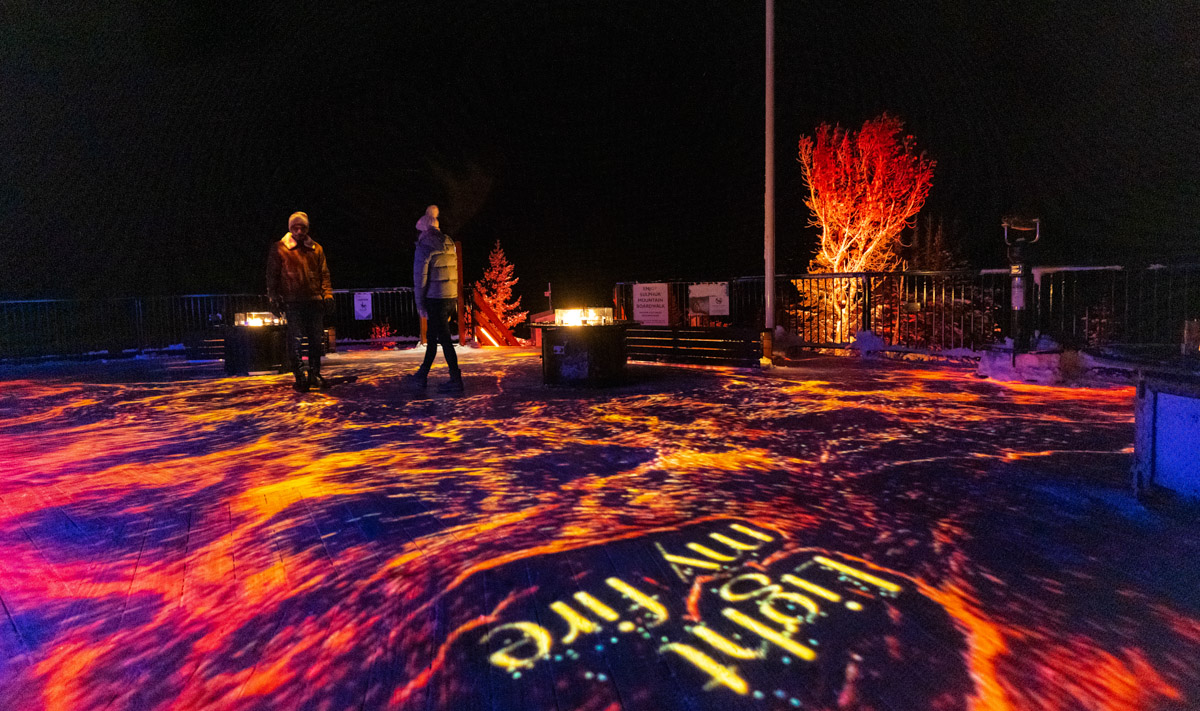

The Nightrise project is a partnership between the Stoney Nakoda Nation, tourism operator Pursuit, and Moment Factory, a Montreal-based multimedia entertainment studio. Together they transform Spiritual Mountain (also called Sulphur Mountain), the sacred territory of the Stoney Nakoda people, into an immersive and culturally-rich sound and light experience through the use of interactive digital art installations.

Installations known as the Four Wonders—Cosmic Rays (Apenene Garharhagach), Diamond Dust (Wiyapta Ptach), Alpenglow (Aîthîya Eya) and Frosted Waves (Yowatha)—occupy indoor and outdoor levels of the summit building until April 10, 2022.

But Nightrise is more than an after-dark attraction. For the Stoney Nakoda, the Nightrise partnership is “reconciliaction”—a term gaining momentum across Indigenous communities, the private sector, and academic institutions in Canada. In contrast to reconciliation, the word is more inclusive and forward-looking. Where reconciliation may focus on apologies and reparations, reconciliaction speaks to lasting change and greater recognition of Indigenous peoples.

“Reconciliaction goes beyond. It’s the next step after reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples in Canada,” says Kirsten Ryder, Director of Training and Development with the Stoney Tribal Administration. “Trust, mutual respect, and equity are essential elements of the partnership,” Ryders says, but “sharing culture and stories, respectfully, and following protocol is critical to reconciliaction.”

Once at the Summit Building, I begin my nightrise exploration at Diamond Dust (Wiyapta Ptach), a blue-black space illuminated with swirling ice crystals. Outside the floor-to-ceiling windows, an enormous Canadian flag flutters high above glowing firepits. Inside, melodic Stoney Nakoda words and music invite relaxation and contemplation. The invitation to slow to the speed of wapa, one of many words for snow in Stoney Nakoda, is difficult to resist.

There is a lot to discover and learn at Nightrise, and each journey through the installations is unique. The creators make local Indigenous history, culture, and stories central to the experience; Stoney Nakoda words (along with English translation) and music add depth and respect. Ryder shares that she “hopes that visitors to Nightrise leave with new knowledge and a positive feeling.” For those who aren’t able to visit before April 10, 2022, Nightrise will return to the Banff Gondola later this year.

Other tourism collaborations elsewhere in Canada are also considered reconciliaction, projects in which sharing Indigenous culture is a critical element. For example, the Squamish Nation, whose traditional territory is in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, is a partner in the proposed Garibaldi all-seasons resort and community on Brohm Ridge (known as Nch’ḵay̓) in Squamish. The tourism and recreation component to the Garibaldi at Squamish development includes the construction of resort accommodation, ski runs, and multi-use trails.

As part of the agreement, the Garibaldi at Squamish project must meet Squamish Nation values and principles; these include employment, wildlife habitat preservation and environmental protection. In keeping with reconciliaction, the Squamish Nation’s Coast Salish history and culture are integral to the resort community’s design and branding. Garibaldi at Squamish will have a visible Squamish Nation presence and provide opportunities to learn about Coast Salish culture through language, stories, and mythology.

While tourism is an accessible way for Indigenous peoples and the private sector to collaborate and share Indigenous stories and culture, are there other spaces where this type of reconciliaction is possible?

“Yes,” asserts Chief Ian Campbell of the Squamish Nation. Chief Campbell offers the Woodfibre Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) project as a reconciliaction initiative outside of tourism. Woodfibre LNG, a Canadian company based in Vancouver, is developing an LNG export facility on the former Woodfibre pulp mill site in Howe Sound. Located about seven kilometres from downtown Squamish, the site is also a historic seasonal fishing village known as Swiy̓át. Before the LNG export project could proceed on their traditional territory, the Squamish Nation issued 25 conditions Woodfibre LNG had to meet.

The eventual partnership and reconciliaction initiative between the Squamish Nation and Woodfibre LNG includes economic benefits for both parties, a significant Squamish Nation role in environmental regulation and stewardship, and the sharing of Squamish Nation culture. According to Ray Natraoro of the Squamish Nation, the nation is interested in “building careers, not filling jobs,” and the Woodfibre LNG project will assist with this objective.

But even the promise of new jobs is not worth any cost. The Squamish Nation raised concerns about Woodfibre LNG’s proposed seawater cooling method harming Howe Sound marine life and habitat. After an independent review of three cooling technologies, the Squamish selected air cooling as the preferred method. Woodfibre LNG has incorporated air cooling into the facility design.

Squamish Nation culture is also integrated into the Woodfibre LNG safety requirements. Like most industrial projects, every person visiting the worksite must take part in a safety orientation. At the end of this fifteen-minute process, visitors also complete a ten to fifteen-minute Squamish Nation safety orientation, and are required to answer questions about the Squamish Nation before proceeding onto the worksite. “This provides a deeper appreciation of where they are and knowledge the visitor can take away,” says Chief Ian Campbell.

Projects that share Indigenous culture and stories are critical to reconciliaction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, and are also “part of the healing process,” says Ryder. Back at Nightrise, as the gondola swoops down the mountain, her hope that reconciliaction can be a force for knowledge and positivity is echoed by the installation.

“Perhaps you feel a little different than on the way up?” the voice of Stoney Nakoda artist Cherith Mark whispers over the speakers, followed by a question: “The night has risen, and what has she left you with?”

Read more Travel stories.