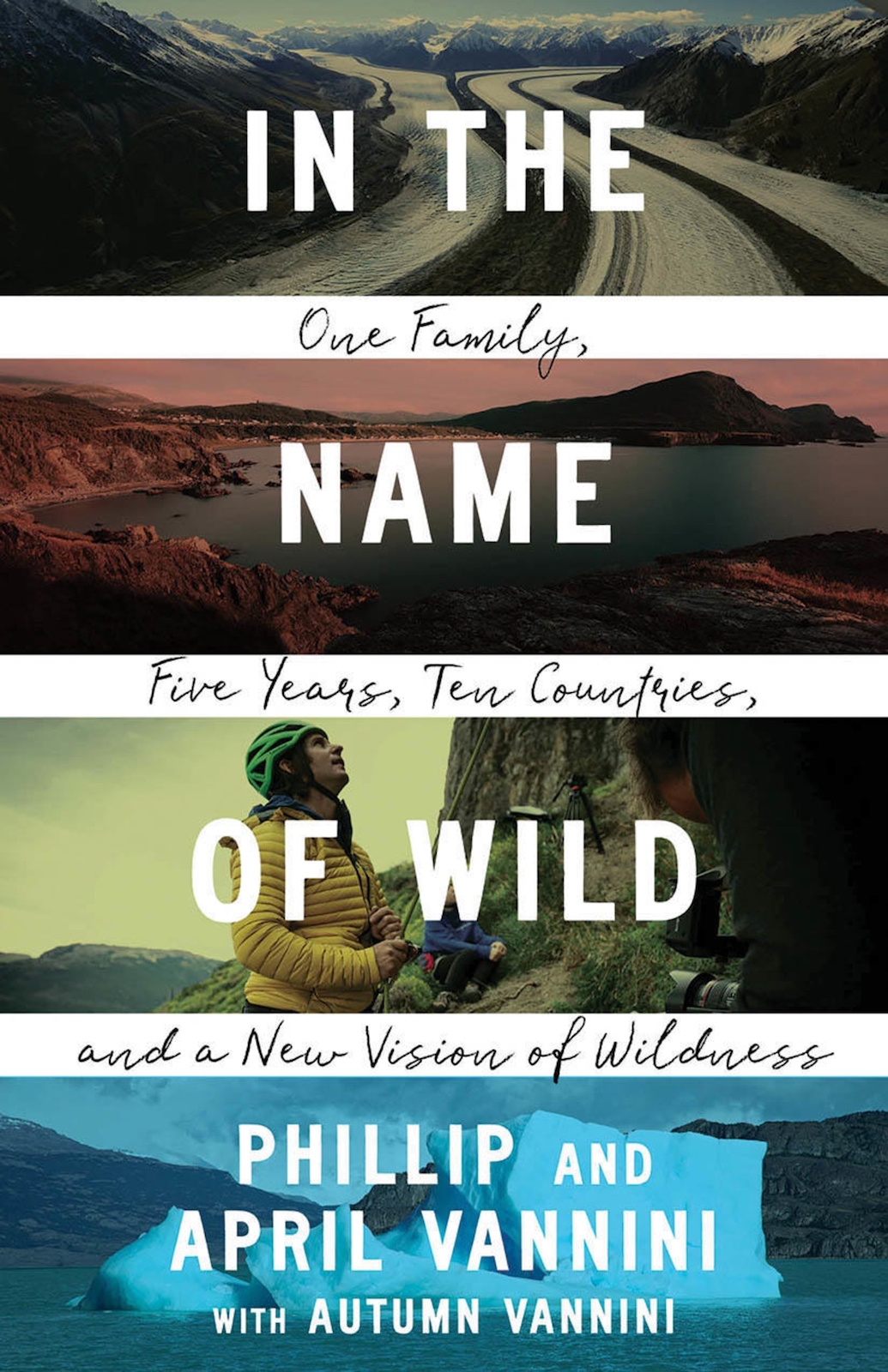

Filmmakers Phillip and April Vannini, whose home base is Gabriola Island, spent years travelling the world with their young daughter, Autumn. This story from the Hollyford Valley, New Zealand, is excerpted from their new book, In the Name of Wild: One Family, Five Years, Ten Countries, and a New Vision of Wildness.

The Western idea of wilderness is deeply interconnected with notions of fatigue, discomfort, inconvenience, and sacrifice. Historically, wilderness began to take root in the Western imagination when urban living became the norm. As cities expanded and urban dwellers became more dependent on the trappings of modern society, a small but growing number of writers such as Henry David Thoreau began penning words about the virtues of excursions to the countryside and the mountains. To spend time away from the city, in closer contact with nature, strengthened the body and reinvigorated the spirit, they wrote. To struggle with primal challenges such as collecting water and food and making shelter was a test of one’s physical and moral fortitude, a fortitude that had been softened by the comforts and conveniences of the city. To spend time in the wilderness, they argued, was a way to go back to the basics, to appreciate the pleasures of deprivation in the name of struggling for achievement.

One of the Vannini family’s many trips took them to the Yukon.

We explained to Autumn that to feel tired was to feel good, nearly quoting Thoreau. Along the same lines, we lectured that to be brave in the face of challenges and to conquer one’s fear were ways to manifest … um … she wasn’t listening anymore. She had turned the corner and sped off. Moments later, we caught up with her. She stood still, staring at the three-wire bridge. “Mom, Dad, what the heck is that?”

We stopped dead in her tracks and exchanged a long look for what seemed like forever.

“Phillip, what is that? You never told me about this!”

“I did. It’s a three-wire bridge. Remember, we talked about it and then we agreed to not worry?”

“Well, we should have worried! What do we do?”

“According to YouTube, we grab the right cable with the right hand, the left cable with the left hand. We need to walk at an angle, kind of like a duck, which will put more body weight on the crossbars that intersect the lower cable. It’s important not to look down at the rushing water because that can be frightening.”

“Your daughter—”

“Yeah, the interesting thing is, she’s at an advantage because of her lower centre of gravity, and we just need to reassure her that everything will be—”

“No, I mean, shut up. Look at your daughter, right now! She’s already halfway across the damn thing.”

There Autumn was—15 feet above the creek, 45 feet away from parental safety, 145 kilometres away from a hospital, and 2 minutes ahead of a proper safety briefing—duck stepping her way to the other side of the gorge. We hadn’t even had a chance to give her a proper tutorial or reflect on the existential meaning of what we were doing and why we were doing it, and she was already too far for us to intervene (only one person at a time on three-wire bridges, or, well, you die).

“Phillip, do something!”

Do what? Run underneath and catch her if she free falls? Call her back for a quick safety briefing? Shout advice at the risk of distracting her? Pray to gods we didn’t believe in?

It was then, amid all this tribulation, that Autumn stopped and turned. She had a blissful look on her face. “Whee! This is awesome! It’s like that thing at the playground!”

The idea of wildness differs from person to person. While we may, as a global society, agree that some areas are deserving of receiving the official moniker of “wilderness” and the environmental protection that goes along with it, individual notions of what wilderness and wildness mean are less clear. What a wilderness is to you is not the same as what it is to us. And what it means to us differs dramatically from what it means to a polar explorer or the average city dweller.

We could suggest that some of these people are right and some are wrong. So maybe the polar explorer is right and we are wrong in thinking we found wildness along the Hollyford Track. But wildness isn’t a fact like a mathematical equation, the length of a river, or the geographical location of the capital of a country. Wildness differs even from a legal standpoint: it changes drastically not only from country to country and in international systems of environmental protection but also within countries or cultures. In this sense, wildness is something akin to a beautiful landscape. What is beautiful to you may be nothing special to us, but you are still entirely within your rights to think of it, and feel about it, however you wish.

And that is why that moment, when Autumn led the way across the three-wire bridge, was the wildest moment of our family life up to that point.

Excerpted with permission from In the Name of Wild: One Family, Five Years, Ten Countries, and a New Vision of Wildness by Phillip Vannini and April Vannini, with Autumn Vannini, 2022, On Point Press, an imprint of UBC Press, Vancouver and Toronto, Canada. For more information go to www.ubcpress.ca.

Read more outdoors stories.