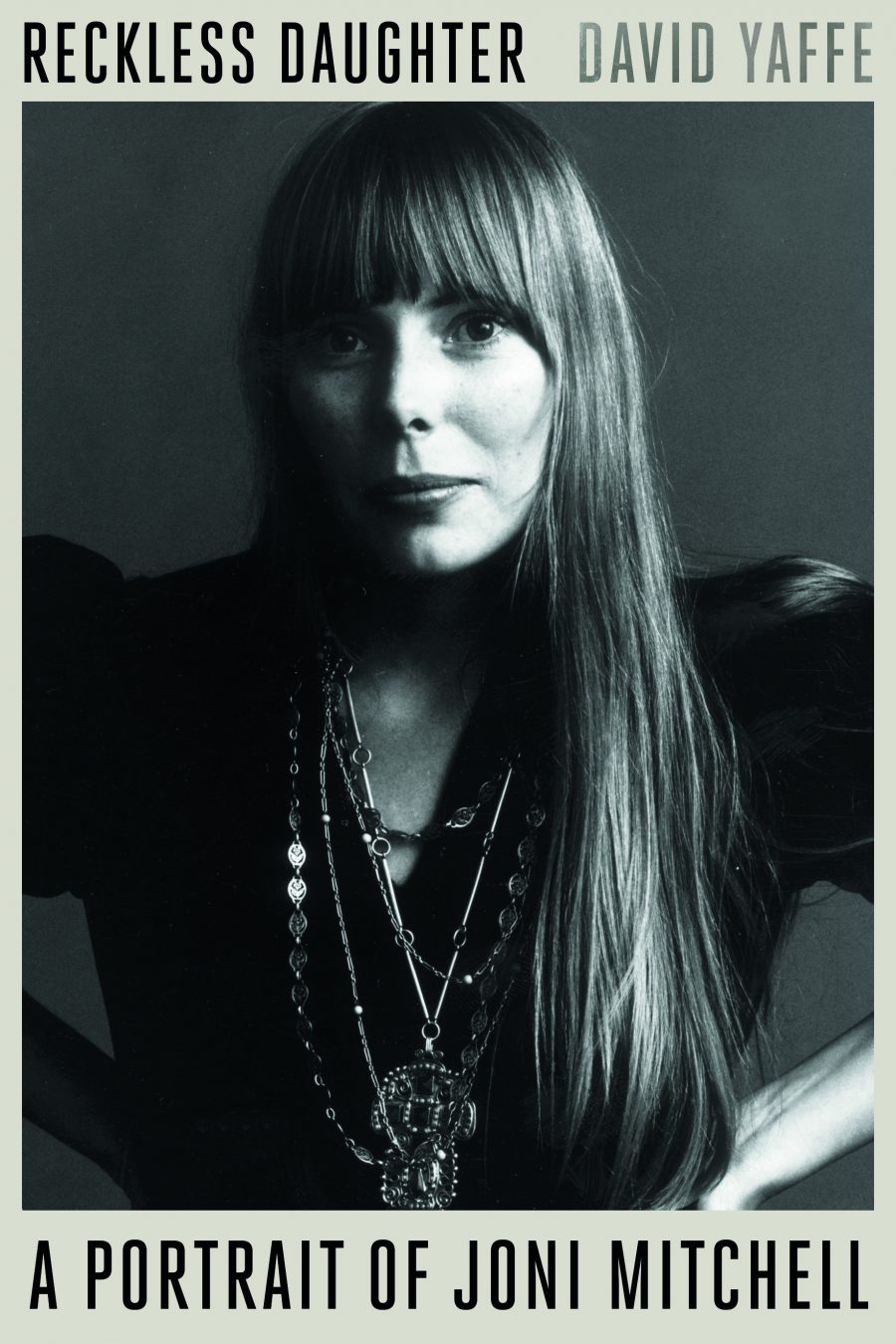

David Yaffe is bemused, clearly, even on the phone from his home in New York. “Yes, it is a bit strange to be the one on the other side of the table, answering questions, not asking them,” he says. The occasion, though, merits his shift in perspective, since his insightful, articulate, simply splendid biography of Joni Mitchell, titled Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell (culled partially from her audacious album of 1977, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter), is now available, and is a must-read.

Mitchell is, famously we suppose, Canadian. She was born in Fort Macleod, Alberta, not so far from Nanton, itself not so far from High River, itself not so far from Calgary. Mitchell in some ways really never left these roots, as her cover version of the Sons of the Pioneers hit “Cool Water” rhapsodically proves, right down to the fact that she does it as a duet with Willie Nelson. But a progression to more populous places was steady; she moved on to Saskatoon, and then the coffee houses of Toronto, then New York, before heading to Laurel Canyon in Los Angeles. All part of the piece, for her. Yaffe had extensive interviews with Mitchell, first in 2007, and then again, specifically for this book, in 2015, with plenty of rock and folk music royalty contributing their two bits. Yaffe elicits the best from them all, really, to create an intimate portrait of an artist who obstinately refuses intimacy, at least on the mass media stage.

The musicians who are part of this book are many and starred: Leonard Cohen, David Crosby, James Taylor, and Herbie Hancock, to name but a very few. Not all are equally complimentary to Mitchell, who herself often spoke her mind, acerbically and sometimes in public. So she had her share of friends, but also of people who did not like her. All agree on one thing, though: she is a great artist rising above, as she puts it in “Free Man in Paris,” the “starmaker machinery behind the popular song.” It is an inescapable irony that Mitchell became famous not as a singer, but as a songwriter. Judy Collins and Buffy Sainte-Marie made Mitchell a star before she had herself written anything close to being a hit. But such songs as “The Circle Game” and “Both Sides Now” eventually became known as Mitchell standards, along with “Big Yellow Taxi,” “River,” “Carey,” and so many more.

Yaffe treats his subject with some deference, certainly, and a whole lot of respect and admiration. “I grew up with a fairly hierarchical idea of art: all Mahler, not Dylan,” he says. “Fortunately, I grew out of that. And I fell in love with Joni Mitchell’s music around 1988, when Chalk Mark in a Rainstorm came out, and then the following year, Night Ride Home. These were powerful, amazing records, and I knew Joni was a great artist.” Yaffe rose in the ranks of music writers, and finally met her, for an interview, in 2007. “I thought it went well,” he says, “but Joni called me when the piece came out, and she was unhappy with a couple of my word choices. She thought they made her seem ‘too bourgeois,’ and she more or less excommunicated me for nearly a decade.”

Mitchell allowed Yaffe back in, for a series of interviews for the book, in 2015. Had she changed much over those years? “Oh, yes. She was much more bitter,” says Yaffe. “She was cutting people out of her life, even people who did not want anything from her.” Mitchell refers to her first husband, Chuck Mitchell, as her “first major exploiter,” and that carries a lot of weight. First, but really the first in a very long line.

Yaffe empathizes with Mitchell, all the while acknowledging that she can be “equal parts charming and vicious.” But his understanding of her, gained over time, is that she is “undervalued, misunderstood. How can people know how difficult it is to be Joni Mitchell? What she gave up, what she gave, far outweighs what she gained.”

An entire chapter is rightfully given to an evening Yaffe spent talking to Leonard Cohen about Mitchell. And Mitchell’s ex-husband Larry Klein, still loyal to her even after suffering her umbrage over many years, provides keen insights into her studio work, how meticulous she always was. Yaffe is enthusiastic when saying, “Chaka Khan was amazing, singing parts of certain Joni songs that made me appreciate them even more. In fact, almost all the musicians I met for this book were wonderful to talk to.”

Yaffe uses the word “portrait” in his book title, and wisely. There is no way to distill such a mercurial, protean figure as Mitchell into anything that might be called authoritative. This portrait, with all its details, critical commentary about key songs, and deep access to important figures in Mitchell’s life, does ultimately provide a caring look, a positive portrait, of a seminal artist who always went her own way and took no prisoners, but provided a musical landscape that countless people have used as part of the soundtrack to their lives. There is never a dull moment in Yaffe’s book; as Mitchell sings it, there is “a lot of wisdom and a lot of jive,” which makes it well worth reading.