Spring has sprung. Summer nearly here. Buffy Sainte-Marie has spent the last two evenings performing songs from her new album and from the duration of a music career that has spanned, now, over five decades. That career is not distinguishable from her prominent role as an activist, for peace, for civil rights, for aboriginal rights, and that has been the idea really from day one, song one. If anything, Sainte-Marie rocks harder, louder, now than she ever has; she remains an irrepressible force.

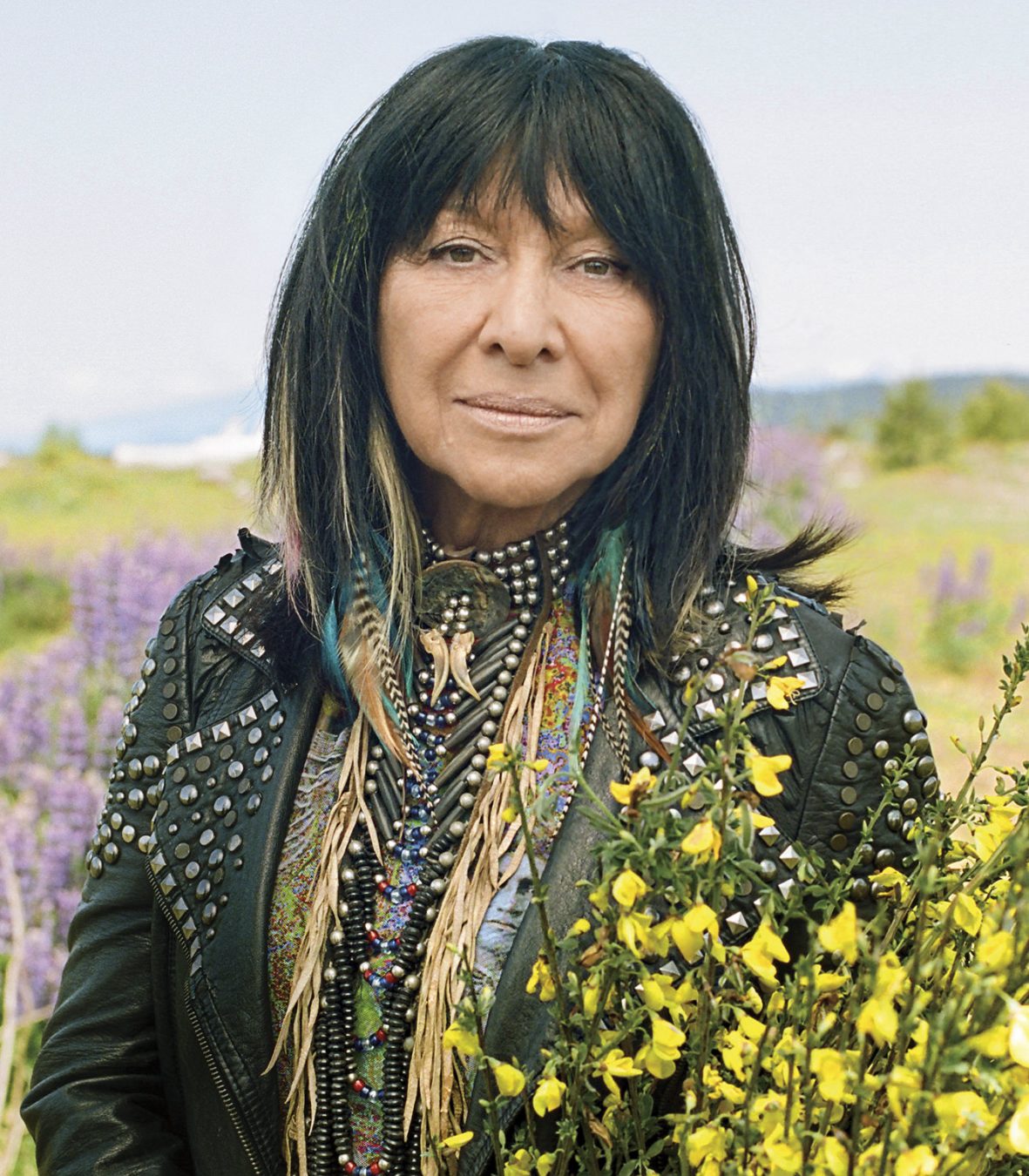

The day is warm enough that she needs no extra blankets or overcoat as she participates in a photo shoot. In addition to her live music performances, including a recent stop in North Vancouver, she also speaks at several dozen events each year. She is all candour and never at a loss for words: “I talk about my career, but also about current events, various causes I see needing help or more awareness, try to make it entertaining, a spoonful of sugar, you know.” The smile is never far from her, and she moves among the cowslips and lupines of Richmond’s Iona Beach, happily reminded of her farm in Hawaii.

The farm is her idyll, a place where “the music business does not exist. It is a real farm, with real horses, chickens, cows, even a few pigs!” That’s why she settled there, having fallen in love with the place when visiting a friend a long time ago. “The music business is a tough one,” she explains. “Back when I started, it was all kind of naïve hippies singing folk songs in coffeehouses. Toronto, New York, a great scene, a lot of it as protest against the big war in Vietnam.” She pauses, adds, “the war itself was bad enough, but the government was denying it even existed. That was just wrong.” Her abiding purpose is to continue her vocation: “The need for people to fight against oppression, of their rights, of the land itself, is stronger now than ever. It’s a lot like the ‘60s today. People are telling us what we can and can’t plant in our own soil. It’s not right.”

“I have seen a lot of the world, and if you keep yourself open to the experiences, the songs arrive.”

For Sainte-Marie, the early protest songs were not quite straight ahead anti-war, anti-government. Her song “Universal Soldier”, covered by artists such as Donovan and Glen Campbell, appeared on her first album, and sprang from a specific incident. “I was sitting in a passenger lounge at the San Francisco airport,” she recalls. “There was a sudden rush of activity, and then three U.S Army medics came through. They sat down, and I went over to talk with them. This was when the government was still insisting the war was not happening. They told me some horrible stories, and one of them said, ‘Believe me, that is the worst war I’ve seen, and it is real.’ I wrote my song over the next two days.” In concert, Sainte-Marie introduces the track with a lengthy talk about its meaning: it is not simply saying the world’s leaders need to make peace, but that individuals must come to grips with their role in sustaining what, for her, are basically feudal tendencies to follow along with orders. In essence, no soldiers, no wars. Her live performances and her private conversations both make it clear these are not mere words for her; it is a way of living. “It’s not about being a naïve singer, but about reminding people they have to stand up for themselves,” she explains.

This kind of thinking imbues her entire repertoire. Even the hugely popular love songs tend to belie a certain rugged individuality, full of compassion and tenderness but not overly sentimental. “Up Where We Belong”, sung by Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes for the film An Officer and a Gentleman, won her an Academy Award for Best Song. “Until it’s Time for You to Go” was a massive success for Neil Diamond, and a substantial hit for dozens of other artists who covered it, including the King himself, Elvis Presley. Songs such as “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” and “Soldier Blue” continue to live, and her music has taken on iconic status, spanning generations. Sainte-Marie has had her songs sung by a virtual who’s who of folk and rock over the years.

In concert these days, the 74-year-old travels with a band consisting of Michel Bruyere on drums, Anthony King on guitar, Mark Olexson on bass, and Kibwe Thomas on keyboards, with herself leading the way through a variegated show that rocks hard. Aboriginal elements appear everywhere in her music, most often in some of the choruses to songs such as the title track from her new album, called Power in the Blood. The band backs her on vocals and the overall effect of the chants and harmonies is powerful.

From coffee with Elvis to breakfast with Mohammed Ali (“a deep spirit, a wonderful person”), Sainte-Marie has had plenty of experiences to drive her creativity and sustain her activism.

The new music is strikingly fresh, original. “I have the medium in mind when I write, but basically the songs just come to me,” she says. “I have seen a lot of the world, and if you keep yourself open to the experiences, the songs arrive.” But what about that fresh sound, and the heavy live shows? “I don’t want to copy anyone, so I try to stay a little ahead if possible.” The opening song, on the album and in concert, is called “It’s My Way”. The song appears on her very first album, of the same name, released in 1964, and seems to capture her message well; and with a heavier, more rock and roll version kicking out the jams, it is more resonant than ever.

Those coffeehouses, where her kin were people such as Joni Mitchell (whose song “The Circle Game” was Sainte-Marie’s first big commercial hit), disappeared as folk music became a commercialized music industry commodity. “Bob Dylan made a lot of money for a lot of people,” she muses. She continued to record, to perform, and has sustained her activism through the decades without flagging.

From coffee with Elvis to breakfast with Mohammed Ali (“a deep spirit, a wonderful person”), Sainte-Marie has had plenty of experiences to drive her creativity and sustain her activism. Her farm provides plenty of time to recharge, to contemplate. But when she takes the stage, native chanting pouring loudly out of the speakers, her drummer doing an energetic, frenetic dance to stir the crowd, she is enlivened. Working with great passion and purpose to communicate through her poetic lyrics and well-crafted songs, through the force of her personality and the power of the music, she is determined now more than ever to not just preach to the converted, but to battle against complacency. It’s her way.

Hair and makeup: Sonia Leal-Serafim at THEYrep.