When the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation turned 100 in 1988, it held a centennial ball at the Bayshore Hotel to celebrate. Ballroom dancers dressed in formal attire from 100 years before, the women wearing long diaphanous gowns and upswept hair adorned with feathers, the men in white ties and tails. Guests filled in their dance cards to spin to the music of band leader Dal Richards, who chose songs from each decade, starting with the 1880s, including waltzes. The Garden Club of Vancouver provided floral centrepieces for the tables and decorations for the Bayshore ballroom, where many “Old Vancouver” families gathered to mark the occasion. British peer Edward Stanley, the 18th Earl of Derby, whose great-grandfather had given his name to both Stanley Park and the Stanley Cup, attended with his wife.

But that was the ’80s. Times were different then: Vancouver had just welcomed the world to Expo 86, Gordon Campbell was mayor, and the average house in the city sold for less than $300,000.

Fast forward a few decades, and the park board may be facing its demise, with Vancouver mayor Ken Sim calling for the city to get rid of the elected board and reclaim oversight of the city’s parks and recreation. Such a decision would need to be approved by the province, because the park board—the only elected body of its kind in Canada—is part of the Vancouver Charter.

Sim says getting rid of the board is long overdue. “The current system is broken, and no amount of tweaking will fix it,” he said in a news release.

Advocates for the park board disagree, saying the board, unlike city council, is independent of pressure from developers, giving it the ability to take the long view that has made Vancouver delights like the Stanley Park Seawall or the waterfront park along Beach Avenue in English Bay possible while maintaining a level of democracy at which individuals can make a difference.

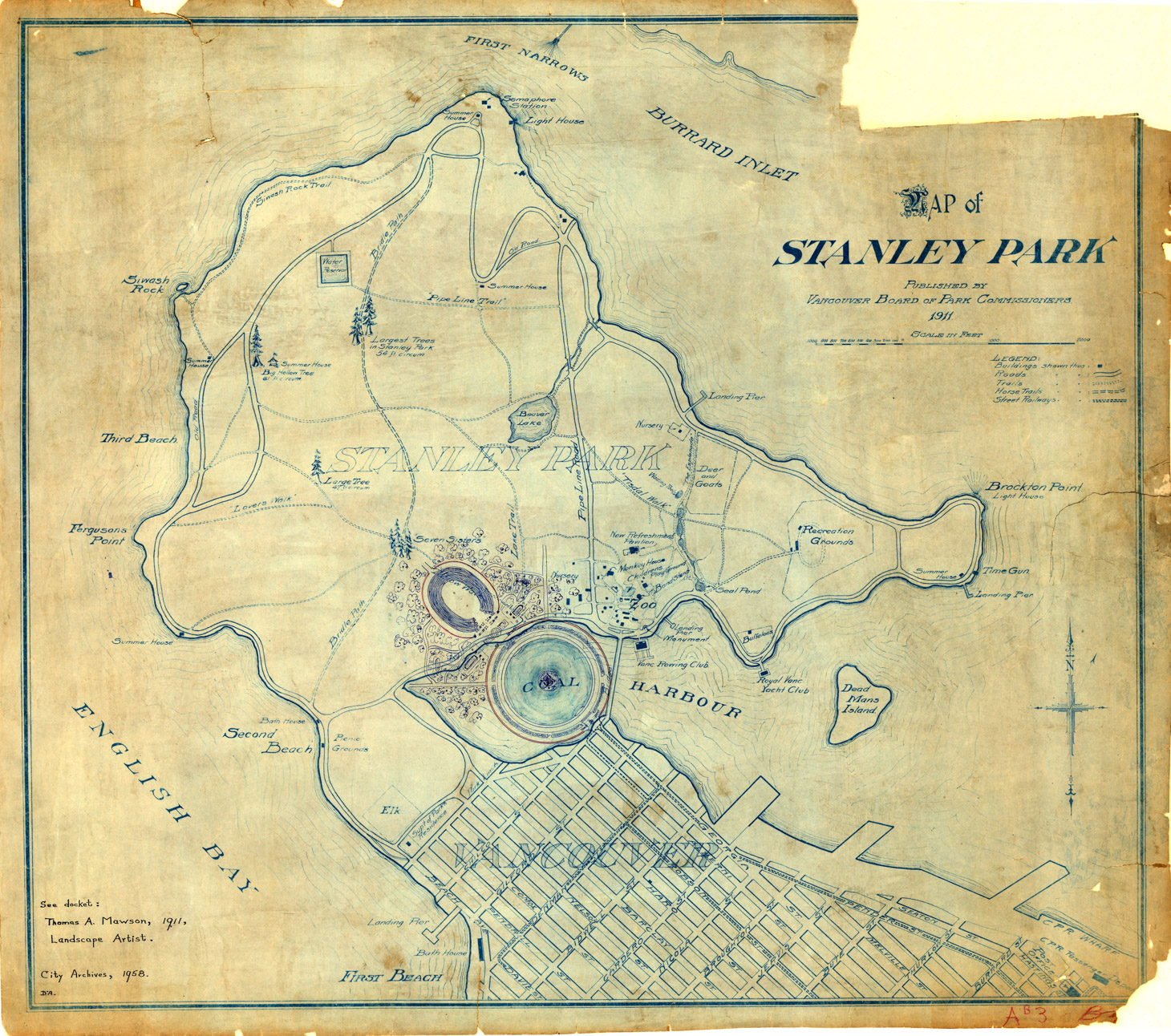

A map of proposed developments of Stanley Park published by the Vancouver Board of Park Commissioners in 1911. Courtesy of the Vancouver Archives.

Today, the board provides, preserves, and advocates for parks, which includes creating new parks, adding playgrounds, maintaining beaches, overseeing community centres, pools, and ice rinks and tending Vancouver’s famous boulevard trees. The park board spends about $168.8 million of the city’s $2.2-billion annual budget, but it also brings in revenues of about $78.6 million from its golf courses, programs, parking, and other sources.

One thing that hasn’t changed since the board was founded is the tension between development and green spaces in Vancouver, a city obsessed with real estate.

“From the very start, the creation of the park committee and then the elected park board a few years later was really, in the beginning, a scheme to protect developers’ lands around the park but ended up becoming stuck in their craw because the park board took its mandate seriously,” says Terri Clark, who worked as the park board’s public affairs manager from 1973 to 2008. Clark, who is now retired, was 23 when she started working at the park board after moving to Canada from the eastern United States. She brims with knowledge about Vancouver’s parks, sharing everything from details about the Centennial Ball to how she came up with the idea for the Festival of Lights at VanDusen Botanical Garden.

The park board was created in 1888, when the Canadian government agreed to lease a 950-acre military reserve to the City of Vancouver for a park. That land would become Stanley Park, named for Lord Frederick Stanley, the 16th Earl of Derby, who was serving as Canada’s governor general at the time.

The park was proposed by real estate agent and federal politician Arthur Wellington Ross, who wrote a letter to Vancouver’s first council saying it should ask the federal government for the land. Some have suggested he didn’t want the military reserve decommissioned and developed into housing, which would devalue houses in the city, while a spectacular park would drive values up.

Stanley Park, much of which is still forested trails, is a top Vancouver tourist attraction, full of quirky highlights like the hollow tree, the miniature railroad, and the nine o’clock gun. In 1888, there was a First Nations village in the park, as well as a squatter village near Brockton Point.

The inhabitants of this village in Stanley Park were labeled squatters because their homes were on parkland. photographed by J. Wood Laing/Vancouver Archives.

The first park board was originally a committee, made up of three elected aldermen (now called councillors) and three appointed citizens. Their job was to oversee the opening of Stanley Park in 1888, but by 1890, an elected park board was in place and two more parks had been acquired: Hastings Park, another military reserve handed over this time by the province, and Clark Park, donated by realtor E.J. Clark.

Although the reasoning for the transition from a committee to an elected board isn’t easy to pin down, for the past 134 years the city’s park structure has been governed by elected politicians independent from city council. At first, there were three elected commissioners, but that was expanded in 1904 to five and in 1929 to seven, the same as today. That first elected board pushed back almost immediately against attempted interference by the city on a decision to buy cages for a menagerie of animals kept in Stanley Park, R. Mike Steele wrote in the book The First 100 Years: An Illustrated Celebration, commissioned to mark the park board’s centennial in 1988.

“As the board is an independent body, its members being elected by the people, they consider it their duty to protect against and if necessary resist any interference with park matters on the part of any body or corporation,” Steele quotes from a letter written by the elected board.

Most cities in Canada have municipal committees made up of city councillors or a mix of city councillors and appointed community members. Vancouver is the only city in Canada with an elected park board.

“The power struggle between the two elected entities seemed never to cease (and effectively never would),” Steele wrote. Some of the goals and visions of early park board staff and commissioners took decades to complete. One of those was the park along Beach Avenue.

“You couldn’t walk down Beach Avenue and see the water because there were houses and apartment buildings all along there, right up to the entrance to Stanley Park,” Clark says. “Through 80 years, we gradually bought up all those residences and hotels and tore them down and made the beach.”

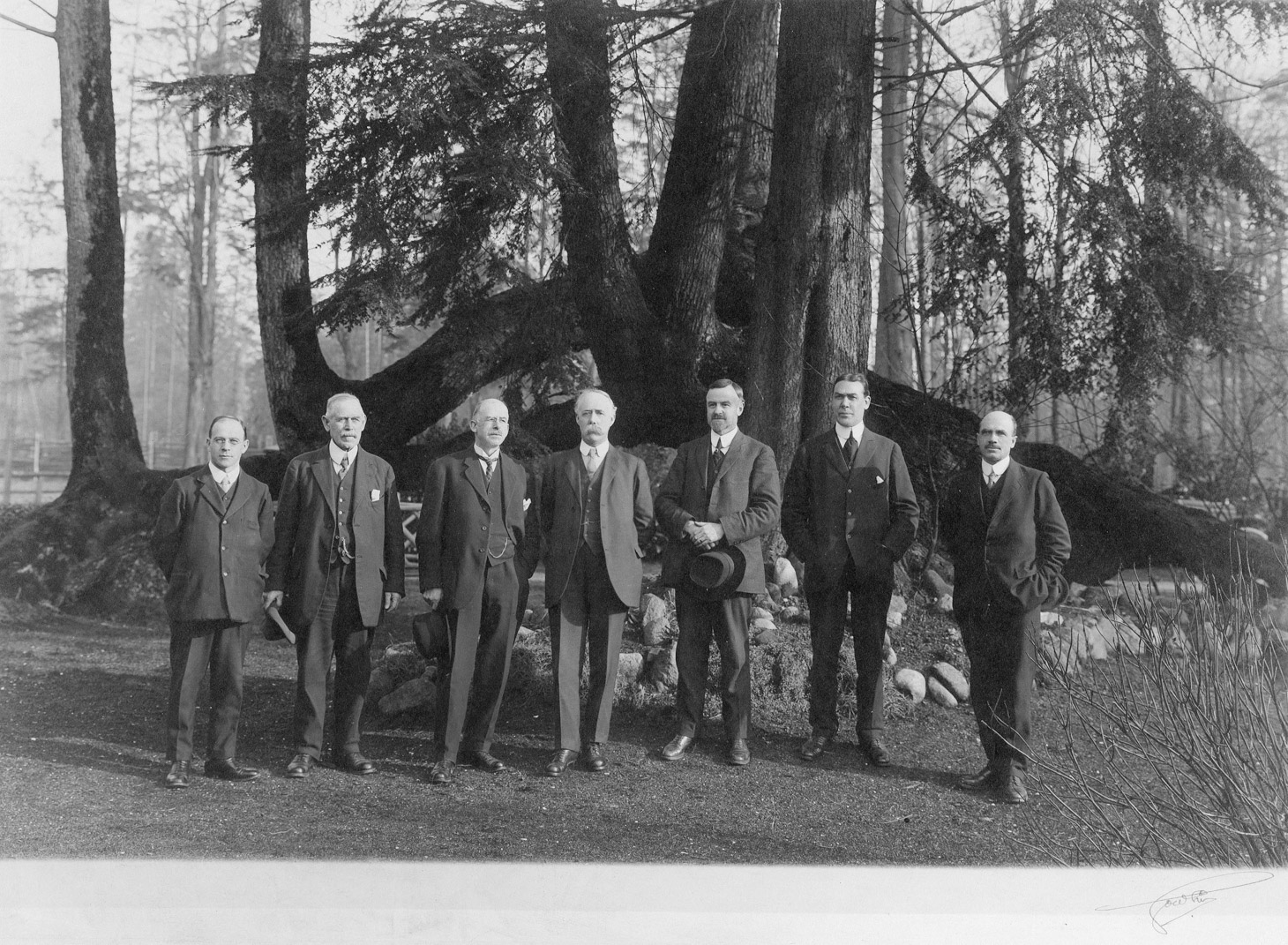

The author’s great grandfather and others gather at the hollow tree in Stanley Park, circa 1906. Major James Skitt Matthews/Vancouver Archives.

The park board tried to do the same on Point Grey Road in Kitsilano and did buy several lots that are now small parks along the waterfront, but when council changed, the political will was gone, Clark says.

The Stanley Park Seawall was another long-term vision manifested by park superintendent W.S. Rawlings. The 8.8-kilometre seawall was begun in 1917 but not completed until 1980. It inspired other seaside walkways in Vancouver, such as those in English Bay and False Creek, eventually creating the world’s largest uninterrupted waterfront path.

“The park board did things incrementally. They had a policy that spanned a century,” Clark says.

A picnic in Stanley Park in 1888, the same year the Park Board was founded. By Major James Skitt Matthews/Vancouver Archives.

The collection of totem poles in Stanley Park—apparently the most visited tourist attraction in B.C.—is another long-term project of the park board, beginning in the 1920s when four poles were purchased from Alert Bay, up to the most recent pole, which was raised in 2009. The poles are a reminder that Indigenous people lived in the park since time immemorial and that Vancouver sits on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations.

Another key player in Vancouver’s parks history is the Canadian Pacific Railway, which received 6,000 acres in Vancouver in return for building the railway connecting the city to the rest of Canada in the late 1800s. That land now makes up some of Vancouver’s premier parks, including Queen Elizabeth Park, VanDusen Botanical Garden, and the civic golf courses, which are often targeted for redevelopment.

Queen Elizabeth Park once served as a rock quarry, which the park board turned into beautiful sunken gardens replete with stunning flower beds and one of the best views of the city. The park is also home to what may be Vancouver’s most expensive public art: Knife Edge Two Piece, a Henry Moore sculpture that is part of a three-piece collection. The other two parts are found on Nelson Rockefeller’s estate and on the Parliament grounds in London, England.

VanDusen Botanical Garden was originally leased by the Canadian Pacific Railway to Shaughnessy’s golf course. A deal was reached to create the park, while allowing CPR to develop housing on a portion of the site. CP Rail continues to play a role in shaping Vancouver. The most recent land deal was made in 2016, when the city paid $55 million for the former railroad right-of-way that became the Arbutus Greenway.

The park board has also faced controversies, most notably because of keeping orca whales in captivity at the Vancouver Aquarium and displacing homeless encampments, but also about interactions between people and coyotes or Canada geese, the need for bike lanes in Stanley Park, new rules that allow alcohol consumption in some parks, and the removal of many trees in Stanley Park due to a looper moth infestation.

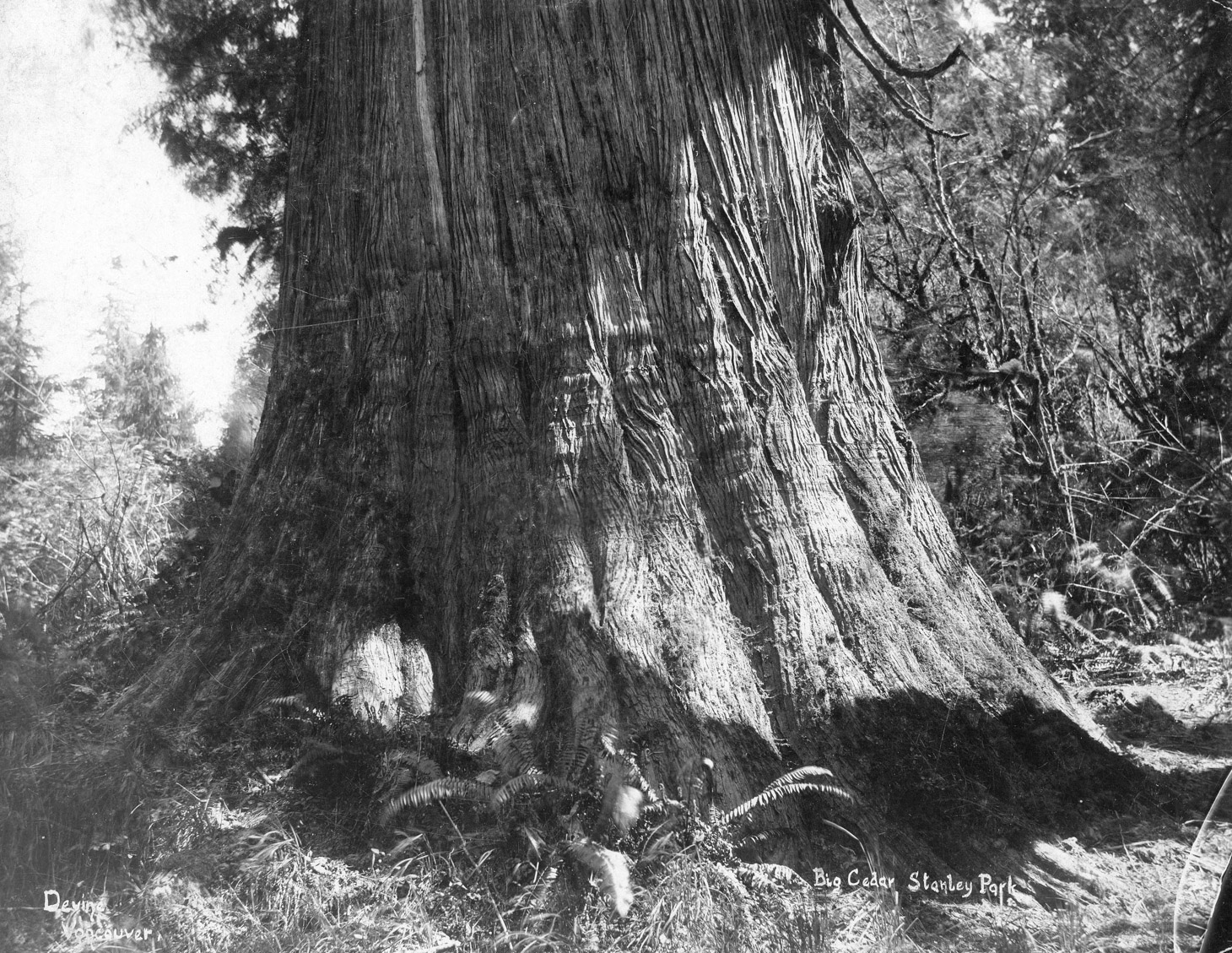

A big cedar tree in Stanley Park, photographed in 1988 by Major James Skitt Matthews/Vancouver Archives.

Those controversies get people involved, and some of those people end up running for the park board, which is a training ground for politics and other civic activism, particularly for women. It served as a launching pad for people such as Niki Sharma, B.C.’s attorney general, Grace McCarthy, who became a member of the legislative assembly and cabinet minister, May Brown, who became a city councillor, Philip Owen, who became mayor of Vancouver, or Libby Davies, who became a member of Parliament.

Sarah Blyth-Gerszak, executive director of the Overdose Prevention Society, served two terms as a park board commissioner between 2008 and 2014. Blyth-Gerszak founded OPS in 2016 and has since worked in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, the heart of the opioid crisis. Her first interaction with the park board was when, as a youth, she started advocating for skateboarding spaces in city parks.

“In a lot of ways it saved my life,” she says. “It changed my life, getting involved in the community, because I really had no education and had no self-confidence. In a lot of ways, I was a youth at risk with no thought of what I was going to do in the future.”

She started volunteering at the Douglas Park Community Centre and was eventually nominated for volunteer of the year. “I remember seeing kids around, so I stopped smoking cigarettes and stopped drinking. I just started to feel like I was contributing to something positive,” she says. “It’s really the most grassroots level of democracy, where you can actually make a lot of change, and you can have a lot of impact.”

She says the consultation- and consensus-building skills she honed while on the park board informs her work preventing overdose deaths today.

The park board was founded as a tool for developers but has evolved into a grassroots level of democracy that has launched many political careers and an independent body that can hold long-term civic visions such as the Stanley Park Seawall or Queen Elizabeth Park and bring them into reality. Its fate now hangs in the balance, with critics calling for its demise and supporters advocating for its future.