Veer to the gas station and go to the stop sign (it’s unmistakable).

Follow the yellow line for a half-mile.

Along this road you’ll drive straight through a weird roundabout thingy.

I’m at the end but there’s no number there.

The driveway is hard to see from road. Look for bamboo.

The front door is by the coloured pots. There’s no door handle.

If you find yourself walking down the driveway too far, it melians you’ve missed it.

This is a sampling of the route markers to Douglas Coupland’s home. Or do they guide you to a portal that throws you into his hyperreal world? It all bears an eerie similarity to the fate of poor Ethan Jarlewski, the central character in Coupland’s 2006 novel JPod, who, in an unfortunate twist of events, is stranded in the bleak hinterlands of avian flu–inflicted industrial China. In exchange for a lift back to Shanghai, Ethan is coaxed to sell his laptop and all its contents—every digital manifestation of his personal life—to who else, the novel’s antagonist, Coupland himself. The author, artist and public figure’s motive? Fodder for his next book of fiction, which turns out to be JPod.

Coupland’s self-referential deus ex machina literary device is a delight that gives the entire novel up to that point—its storyline, layout, typographic design—a clever new context. And while, admittedly, it may be a little self-indulgent to think the mastermind has you pegged for his next sinister plotline, Coupland’s work, including the curation of his own persona, is an exercise in contrasts, where the lines between reality and fiction, digital and traditional, public and private, are often blurred.

Coupland’s directions reveal as much about the path as the man and his astute observations of the physical and social environment around him, a trademark of his artistic practice and writing style. It’s through Coupland’s lens that the mundane, ordinary aspects of life—the normalized behaviours, the objects we interact with on a daily basis but accept at face value—are refracted back to us to reveal their social or cultural meaning, sometimes even their absurdity. His characters are the bit players and beta personalities of the world, who remind us of everyday people we ourselves know and loathe or love in our own lives. InJPod and Generation X, it makes you LOL. In Hey Nostradamus!, it makes you :’( .

Thirteen novels, two short story collections, eight non-fiction works, seven dramas or screenplays, three post-secondary degrees, three honorary doctorates, numerous permanent public artworks in cities across Canada, countless solo and group exhibitions at galleries, museums, and art fairs worldwide. Coupland has even designed a clothing collection in collaboration with Roots Canada. The details are all there on his website and on Wikipedia, and with over 417,800 Twitter followers, what more, really, is there to add about a creative mind as prolific and well-documented as Coupland’s? His own line in “A radical pessimist’s guide to the next 10 years”, a list of 45 survival tips he wrote for The Globe and Mail’s October 8, 2010 edition, is apt: “16) ‘You’ will be turning into a cloud of data that circles the planet like a thin gauze. While its already hard enough to tell how others perceive us physically, your global, phantom, information-self will prove equally vexing to you: your shopping trends, blog residues, CCTV appearances—it all works in tandem to create a virtual being that you may neither like nor recognize.”

“Here’s the thing, we’re doing a profile right?” Coupland remarks. “That’s like scrimshaw. It’s an art form that’s borderline extinct. In fact, it’s almost kind of retro that we’re doing this. Maybe the profile is going to come back. Or maybe you have to reinvent it first.”

Weighty advice from someone who does so effortlessly; Coupland has penned biographies and created artworks that have interpreted the lives of some of Canada’s greatest: Marshall McLuhan, Terry Fox, the Group of Seven, Emily Carr, soldiers in the Battle of 1812, the country’s fallen firefighters. “All dead people,” Coupland says, flatly. “I realize I sort of have this sub-career of documenting dead Canadians, which is not something I set out to do. And at the moment, I’m weirdly respected, and I don’t know where that came from. I think it’s because my hair has gone prematurely white.”

Of course, Coupland has his adversaries too, who criticize his literary ability, his persona, his relevance. But that comes with the territory: Coupland’s first novel (published at age 29 in 1991), Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, is proclaimed to have defined the times it was written in, and he has achieved similar acclaim when writing about Vancouver (City of Glass), Canada (Souvenir of Canada), corporate culture in the tech industry (Microserfs; JPod), and the human experience in general (all the rest). As such, public expectations are high. But at home, Coupland is remarkably calm, quiet, reflective, and in some ways shy, even—almost an antithesis to what you might expect. And to see his mind at work, the wheels turning as he processes stimuli, is remarkable. “See, now you are seeing me in my thinking out loud mode, which no one ever sees,” he quips, mid-thought.

“I like writing about these universes that are still under the radar, or that are not culturally visible yet. There is a lot to be said for pursuing seemingly useless things.”

Coupland churns out a series of seemingly superficial observations, like the fact that tekka maki rolls are sold at the Lonsdale Chevron gas station, and that ready-to-plant cedar hedges are sold at local supermarkets all over town. Then he underscores that these things are actually Vancouver-only phenomena. “People must come to this city and think, ‘What the fuck is with you and hedges?’ There are all these really self-evident things out there once you realize it, once you start to look at them harder, once you start to aestheticize them,” he says, comparing this thinking to that of his idols of the pop art era. “Back in 1962, people were driving around to huge motels and restaurants—signage everywhere. It wasn’t until Andy Warhol said, ‘okay, it’s pop,’ that you saw it that way. And then you could never see the world the way it used to be. I ask myself, what else can we look at that’s actually an aesthetic, but we haven’t yet discussed it as such? I like writing about these universes that are still under the radar, or that are not culturally visible yet. There is a lot to be said for pursuing seemingly useless things. We’re social creatures, so to be interested in, and watch carefully, what people are doing, is a very high expression of what we are about as a species.”

Glance around his house, or at any of his “stacked” artworks, and you quickly understand that iteration is a major theme. Today, the University of British Columbia Library has accumulated over 200 boxes of Coupland’s personal effects: notepads, early drafts and manuscripts, prototypes and moquettes of artworks, fanmail and professional correspondence, samples from the Roots Collection, ephemera, and works in progress—anything and everything that documents his process from concept to creation. As lead archivist Sarah Romkey says, “We sometimes have to rethink what we consider an archive, when we’re working with Doug’s material. We learn a lot about our own practice as archivists—what you keep and how you organize it. Sometimes it’s hard to understand why a piece of ephemera, like a Gap receipt, a boarding pass, or Styrofoam cups, is significant. But then you look all the way down the road, and you gain a new understanding or perspective on his work. Getting lost in the contents is an occupational hazard, for sure.”

There is also the interdisciplinary aspect of Coupland’s work, the seamless intertwining of digital and traditional modes of creation, that presents other challenges, and opportunities. “Coupland’s digital archive will probably be the most complicated ever,” Romkey laments and enthuses at once. She points to a series of collages that demonstrate his fusion of art, design, and technology. Coupland created them while on a book tour in the mid-nineties, affixing receipts, tickets, and product packaging to airplane safety guides or planks of wood with glue and elastic bands, whatever he came across during his travels. He would then send them by courier to his partner back home, who would work with a computer technician to scan and upload them to Coupland’s website, in what is believed to have been one of the first blog-like formats to appear on the Internet.

Lately, Coupland’s artistic practice has largely been informed by his pursuits in the digital sphere. In his 2010 exhibition and series G72K10, Coupland revisited famous Group of Seven artworks by vectoring their likeness in Adobe Photoshop and repainting them on everything from canvases to canoes. The past informs the present, and the present informs the past. Similarly, his breaching, pixelated orca statue, publically displayed along Vancouver’s harbourfront, is an interpretation and manifestation of the physical world as seen through the lens of the digital age.

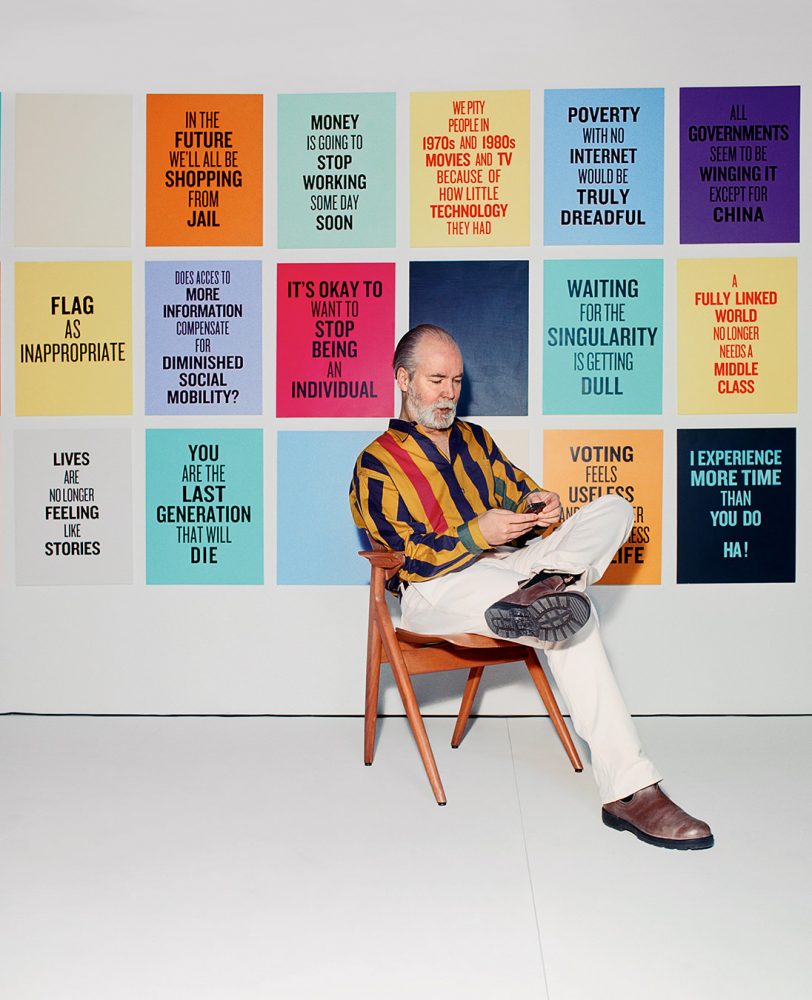

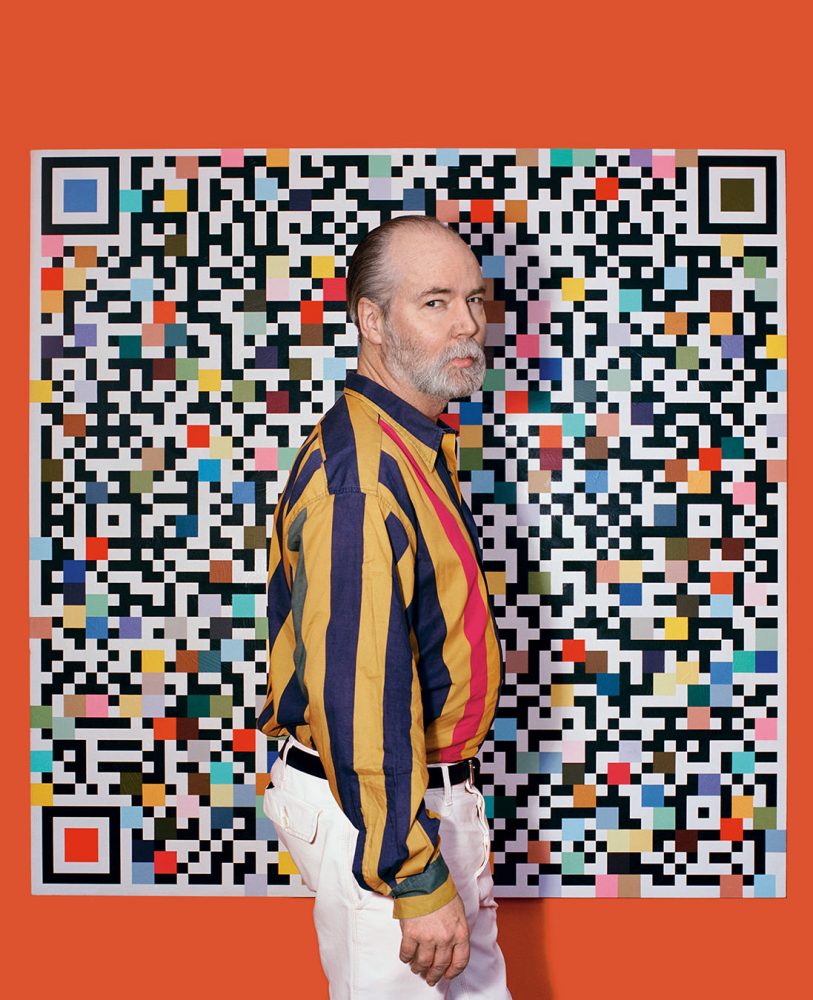

Slogans for the 21st Century is one of Coupland’s latest series. The text-based artworks were recently presented in a solo exhibition at Toronto’s Daniel Faria Gallery, where Coupland is represented. The words “being middle class was fun” and “it’s okay to want to stop being an individual” can be understood as protests, affirmations, epithets, and more, depending on the context in which they are perceived. (Just imagine seeing one on a t-shirt, or as a billboard.) At the Daniel Faria Gallery, however, they were presented alongside large-scale paintings of multicolour pixelated QR codes, which are capable of being scanned by a smartphone to display statements about life and death written by Coupland. “Imagine a car crash that never stops,” one begins. Despite their cheerful appearance, together, the two bodies of work are rather haunting and aphoristic.

This past November, Coupland was recognized by Canada’s design museum in Toronto, the Design Exchange, as their inaugural Gamechanger, an award that will annually honour an “internationally acclaimed designer who effortlessly moves between creative disciplines, consistently demonstrating an expression of creativity across all platforms”. There’s no better candidate to kick off the campaign.

“It’s always nice to have your work recognized,” Coupland remarks. “And it makes me think about what it is I’ve been doing. It’s more of an acknowledgement that you can take one sensibility, and sort of apply it to another medium, or another practice. I call it ‘never leaving art school’.” But don’t mistake this philosophy for some puer aeternus complex. What Coupland means is that for him, creativity is creativity, and the idea should dictate the form. “In my head it still feels like 1983, in terms of getting all the neurons firing at the same time. I don’t see that much difference between these things. I realize, oh you know what, I’m a visual thinker, and so it’s very easy for me to think of ‘words plus images’.”

He continues to meander down that road: “When I look back on my work, it’s like driving past a school I used to go to a long, long time ago. When I started writing, people would say, ‘Oh, this is going to become dated. This is just a passing thing.’ And now, 20-something years into it, what was once something that people thought would become dated, has become a sort of time-capsule.”

Dust off a copy of Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. Strangely, the same sense of foreboding is still palpable. The concerns then, of over-education, lack of employment, and all-encompassing corporate and consumer culture, still pervade. It makes you wonder if we’ve really progressed at all. But what separates this generation from the one Coupland wrote about, is that now new tools exist that serve as coping mechanisms. It has never been easier to escape without leaving, to arouse the senses, and to find humour, information or inspiration. It has also never been easier to create or curate, to innovate, or to communicate.

The speed of technology has taught us to adapt, while corporate messaging has encouraged us to dream and desire. These things conspire to incite impatience and urgency. But as for how it will all translate to economics, politics, or civic or social life—we’re only beginning to see and understand the implications of that. Coupland won’t be able to provide us these answers, but he may hold a mirror up to us along the way.

The years don’t matter anymore. It’s more like technological assaults on our psyche every day that are what really measure time. The book happened in the 14th or 15th century. TV happened in a big way in the fifties. Now we’ve got the equivalent of the TV, multiplied by the book, to the power of data, all multiplied by the number of people on earth, times one terabyte for gratuitous “wahhhhh!” Our brains are barely wiring us up to take us from one thing to the next. I think everyone is saying, “Oh god. Okay. What pimple-faced geek in California is going to do something that’s going to fuck us up again and again and again?” And you know, I think we’re doing a pretty good job of dealing with that, all things considered.