The fog drifts by the snow-capped mountains of British Columbia’s Upper Fraser Valley in puffs, like the breath of a giant on a frigid day. Could there be giants roaming in the unexplored mountain ranges of the Pacific Northwest? Bigfoots? Sasquatches? Huge, hairy, human-like creatures that emit a pungent scent and a piercing screech? It’s a question that consumed the late John Green for much of his life.

But before Green took the sasquatch seriously, he made it into a front-page farce. After working for daily newspapers in Toronto, Vancouver, and Victoria, the award-winning journalist purchased the Agassiz-Harrison Advance in the 1950s and moved to the rural area to raise his family. One April Fool’s Day, in community newspaper tradition, Green printed a fake story. Little did he know that his yarn about a sasquatch kidnapping a woman from the Harrison Hot Springs Hotel would foreshadow his future as the one of the world’s most famous cryptozoologists.

A few years after the faux newspaper article circulated, the elusive man-beast made headlines again—this time, thanks to the Harrison Hot Springs council, which playfully proposed a sasquatch hunt to celebrate British Columbia’s centennial. Men stepped forward to head into the woods and women volunteered to be bait. While funding was not granted, the publicity was priceless, and it had a ripple effect: people started coming forward with their own sasquatch stories. Green’s interest was piqued.

One story that surfaced was of a sighting some 13 years earlier in Ruby Creek, not far from Green’s home. A young girl had been playing in the garden when an ape-like creature allegedly approached her, according to The Province newspaper. The girl screamed out and her mother rushed over, spotted the beast, scooped up her daughter, and bolted for the bush with her other children. The paper reported that this “huge bear” left behind “paw” prints the size of a newborn baby with five feet between strides. The Province later covered a second sighting, this time referring to the beast as a sasquatch. Green wanted to know if this tall tale could actually be true, so he set out to speak to people close to the case.

With a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University, Green brought a special skill set—a deep understanding of human nature and a healthy dose of skepticism—to his sasquatch studies. But after deeming the Ruby Creek affair plausible, Green was hooked. He went on to travel all over western North America to join sasquatch searches, inspect footprints, and interview witnesses—including Albert Ostman, who claimed he was abducted from B.C.’s Toba Inlet by a sasquatch and held captive for nearly a week; and Bob Gimlin and Roger Patterson, the men behind the highly scrutinized 1967 film that shows what’s believed to be a sasquatch strolling across a sandbar in Bluff Creek, California. Green later visited Bluff Creek and saw footprints as long as his forearm—an experience that had a profound effect on him. “The impact is with me to this day,” Green said at the 2011 Sasquatch Summit in Harrison Hot Springs, which was a tribute to his 50 years of steadfast research. “Yeah, this is real.”

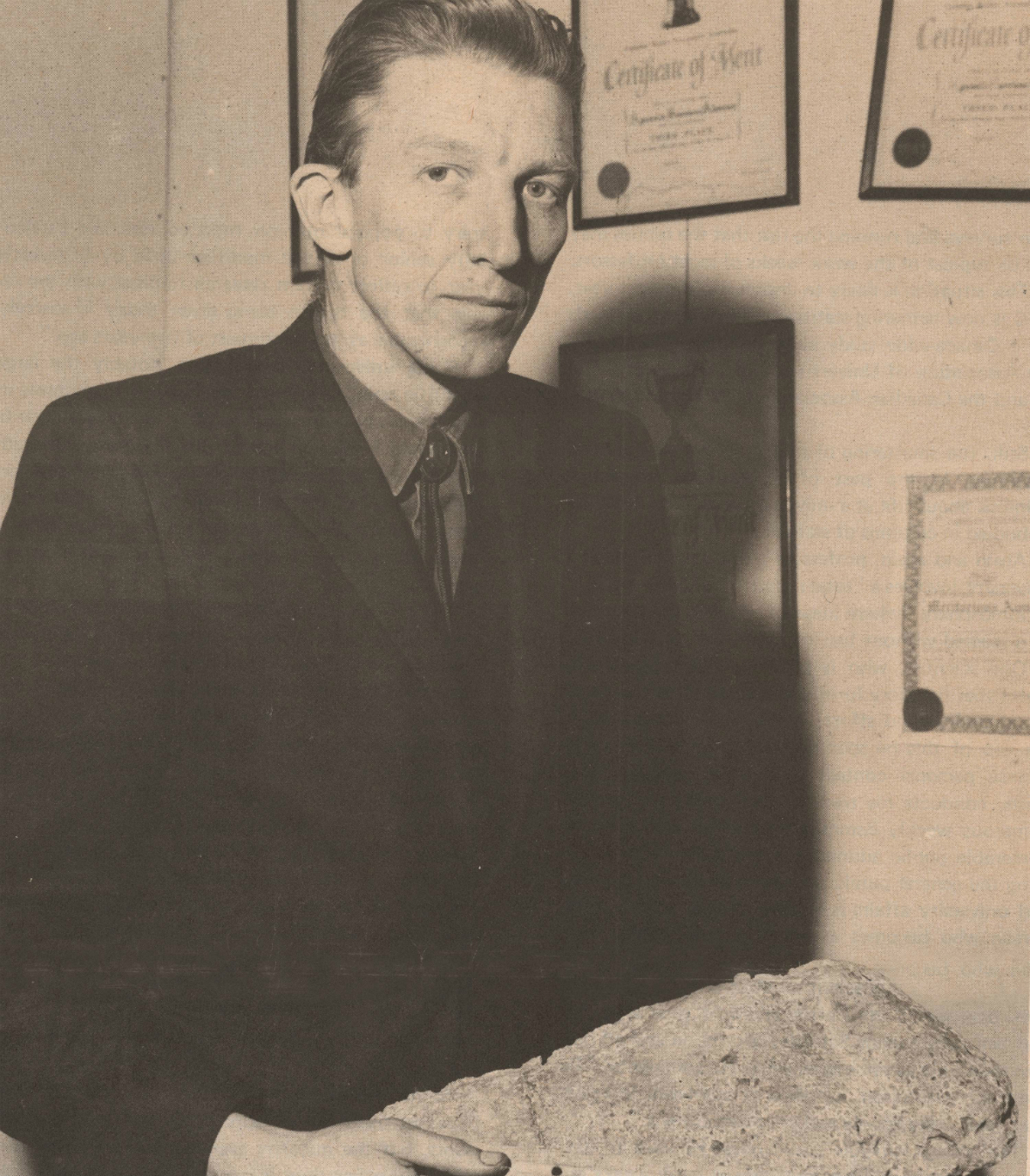

Photo courtesy of the Kilby Historic Site.

In the 1970s, Green developed a process for recording data about sasquatch sightings, which included completing a comprehensive questionnaire. Over the years, he compiled a massive database of sightings, each one written out on a recipe card and marked on a map with corresponding pins. With more than 4,000 records of sightings and over 3,000 records of footprints, it was the largest such database of its time. (In the 1990s, Green transferred the information to a computer, and later made it available to all online.)

Neither a kook nor a maverick, Green was a realist who was highly respected in his field and his community. He was involved in the local search and rescue, Boy Scouts, and Lions Club. He served on the Harrison Hot Springs municipal council for several years, including two as mayor, and was also involved in provincial politics. His lobbying efforts preserved the 1906 Kilby Historic Site in Harrison Mills as a designated heritage location; today, an exhibit dedicated to his work is on display there in what was once a hotel room. In the small space, Green’s old desk and filing cabinets are set up with the drawers pulled open to showcase his research, letters he sent to government agencies and philanthropists to get funding for sasquatch searches, and all those recipe cards documenting sightings.

“This is one man’s lifetime of research,” says Jo-Anne Leon, the sales and marketing manager at the Kilby Historic Site. “It’s amazing how someone can be so dedicated to a subject, and he also had a passion for history. If it wasn’t for him doing over 30 years of volunteer work to keep this place as an historic site, we wouldn’t have this museum at all. So the exhibit has a lot to do with who he was besides the sasquatch hunter. It’s a tribute to all of what John Green stands for, and his lifetime of volunteerism.”

The exhibit, on loan from Green’s family, also includes a sasquatch skull replica and footprint castings made by Green, as well as some eight-millimetre film footage from his travels, digitized and playing on a loop. The collection includes the famous Patterson-Gimlin film, but it can’t yet be shown as Canadian rights don’t become public domain until 2018. “Our hope is to expand the exhibit to include this precious, priceless piece of footage that shows the sasquatch running through the woods,” says Leon, who has seen the film. “I got goose bumps. It was hair-raising.”

This story from our archives was originally published on December 3, 2016. Read more history stories here.