There are three ways to observe a bird: You can see it, you can hear it, or you can read about it in a bird guide. These three are not the same. Take, for example, the boreal owl. In a book you’ll read that it’s a common owl in northern Europe, but the likelihood of spotting one in the dense forests or bogs where it hunts and breeds is slim. Velvety feathers make it silent in flight, and the dark-brown colouring and whitish spots help it blend into the branches it perches on. But up close, in real life, its chocolate-brown feathers are so soft you feel like you’re holding mousse. The white flecks are so detailed they look like they were applied with a delicate paintbrush. And the eyes are such a rich yellow that they hold you spellbound. How do I know? I’m holding one in my hands.

On a crisp evening in early October, my boyfriend and I wind along rough gravel logging roads, weaving deep into Slovenia’s Jelovica Plateau. Headlamps flash in the thick bush, and we join the crew stringing what look like volleyball nets through the branches. Used by bird and bat researchers, these mist nets are made of netting of various sizes and built with baggy pockets that support an entangled animal until researchers can retrieve it. This is the annual owl-banding night. The organizers are our friends, members of the Slovenian chapter of BirdLife, a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that saves birds and their habitats through research, education, and conservation.

I don’t often get the chance to hold a bird, let alone an owl. Instead I flip through Collins Bird Guide for Britain and Europe to identify birds I’ve glimpsed while trail running, whitewater kayaking, or ski touring. Examining the meticulous images and succinct descriptions, I get to know the birds—and through them the landscapes—of my outdoor playground. Until a few years ago, when I started dating an ornithologist and moved to northwestern Slovenia, that was the order of it.

But since getting involved in small volunteer initiatives—netting boreal owls in the thick forest of Slovenia’s mountain plateaus, ski touring to spot the elusive and well-camouflaged ptarmigan in the high alpine, whitewater kayaking to survey waterbirds on frost-dusted gravel bars—backcountry bird surveying has become part of my annual outdoor-adventure routine. And it has given me both a profound new respect for information that is easily available at the flip of a page and also a deeper understanding of winged wildlife.

What pop media has dubbed “citizen science,” the birding community has done for decades. It involves observing (or hearing) birds in the wild and recording the data, putting together tiny pieces of the massive puzzle of information that goes into research and is eventually published in bird guides. Occasionally the chance arises to get a bit closer.

We hit play on a small battery-powered speaker, and the territorial call of the boreal owl rings out. The goal is to trick nearby owls into thinking there’s an intruder in their territory. When they fly by to inspect, they are caught in the mist net. Further along the road, the call of the pygmy owl loops from another speaker. And further still is the base camp where a pot of wild-game stew simmers on a fire, ready to warm up 20 bird-lovers and experts. This informal research night combines science and camping, camaraderie and research, amongst like-minded bird-lovers. Conversations around the fire flow seamlessly from deep debate to brotherly banter. Nets are checked at 30-minute intervals from sunset to sunrise, and each bird is banded, measured, and weighed by the experts. Volunteers get the privilege of observing the process and the owls themselves up close. We help set up nets and carry equipment. And, sometimes, an amateur like me gets to help with the release.

It’s a long night of waiting and intermittent action, but banding birds is a sustained effort, the goal being to repeatedly catch an individual to compare data on growth, distribution, migration pattern, and lifespan. As with all bird surveys, it’s the long-term and consistent efforts that yield results: data and patterns that ultimately contribute to species conservation. At 3 a.m., when everyone except the bird banders have retired to tents, another boreal owl flies into the soft net. A silent celebration ensues, as this particular owl has a leg band and is identified as one caught and banded last year—a small but significant win for nocturnal research.

Every time I kayak on my local river, the Soča, I see a dipper. Its silhouette is apparent even from a distance: compact build with a short tail cocked to the sky and distinctive white breast on the otherwise sooty black-and-rusty-brown plumage, often appearing puffed up, as if it’s wearing an oversized winter jacket. But it’s the unmistakable dipping action that makes the bird easy to spot, even while I’m navigating rapids, and also gives the dipper its name. They curtsey, perched on boulders, before flying directly into the water, where they swim using their wings and can even walk on the bottom, hunting for insects.

In the winter months, dippers appear in great numbers on the Soča. When small mountain streams are trapped under ice and snow, the birds migrate down to the larger river to feed. I love watching their playful dipping and sporadic flight—which includes landing directly in fast-moving water, diving under for insects, then bobbing to the surface to gorge.

Once a year, I pay special attention to this semi-aquatic river resident, counting and recording each individual spotted. The International Waterbird Census (IWC) is held across Europe on the same January weekend each year. It isn’t until I join my boyfriend for this census that I truly understand the amount of time, experience, and knowledge contributed to the concise map I previously took for granted while leafing through Collins.

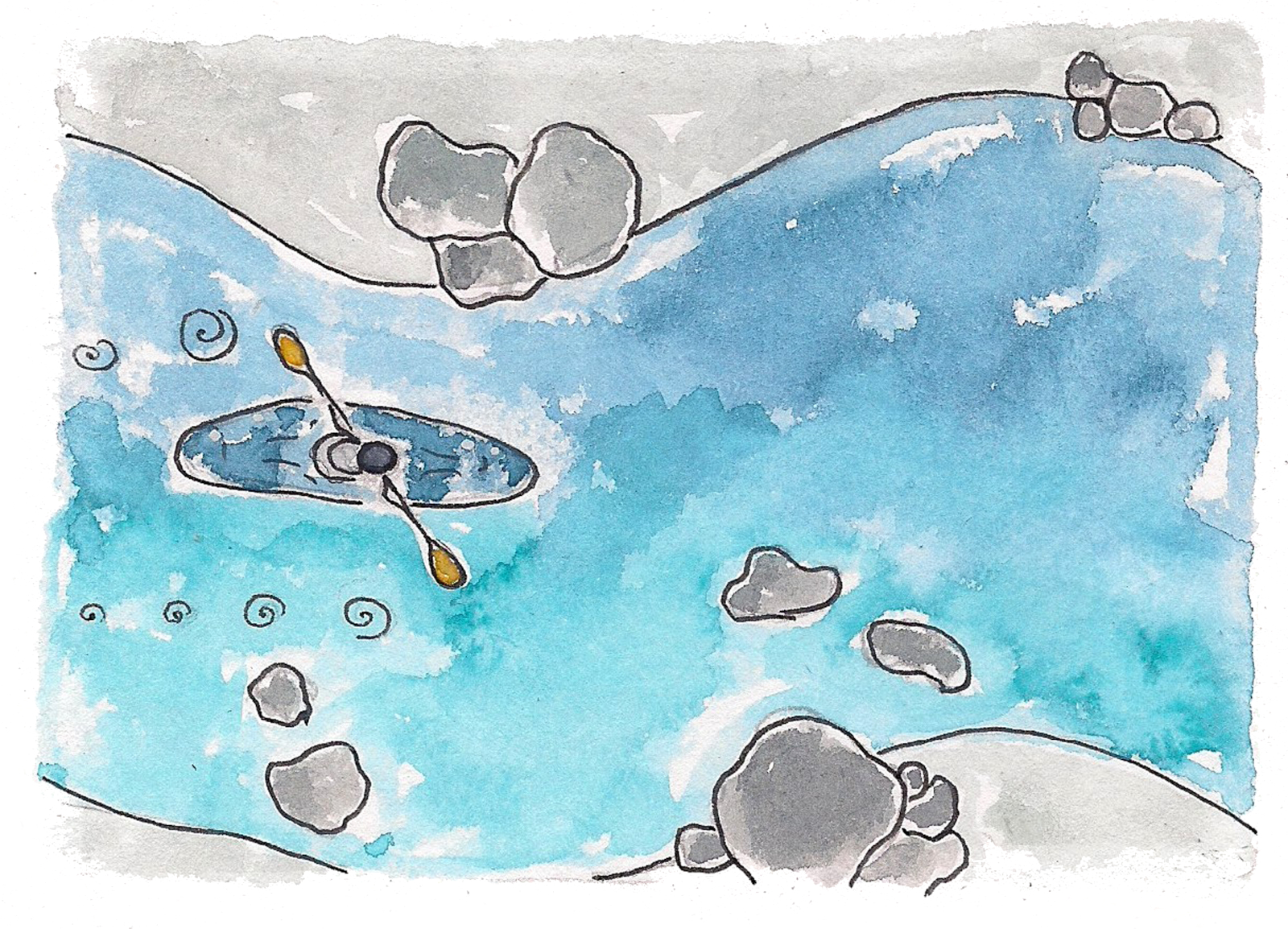

My cream-soda-orange kayak skids along the icy riverbank before splashing into the frigid water, marking the fourth year I have participated in the IWC (and the 25th year for my boyfriend, an avid birdwatcher since childhood). It takes us about seven hours to paddle 24 kilometres along the Soča River and survey two IWC sections, what would otherwise take a team on foot two days. Paddling slowly, we focus on observation (and staying warm and dry), working as a team to count and record every water bird spotted.

I must look like a confused outdoor sports enthusiast returning from the trip, with ski goggles over my whitewater helmet, life-jacket buckles frozen solid. Back home and defrosted, we enter the data into an IWC online database publicly available to bird researchers globally. This census contributes to ongoing research and is also a launch point for more detailed studies.

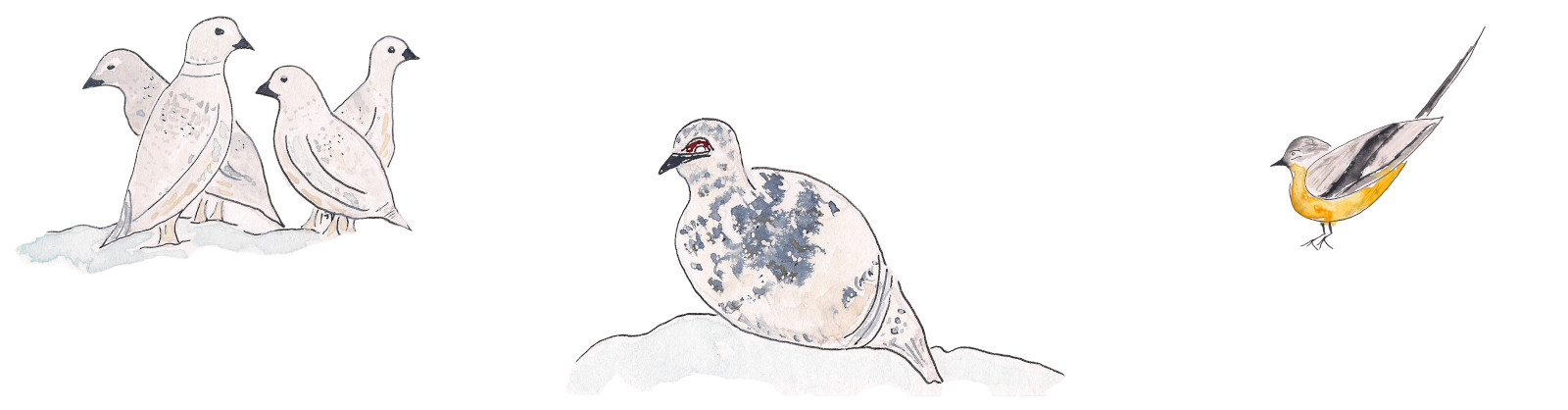

The mountains of Slovenia are a harsh environment in winter, the kind of landscape where fur seems more practical than feathers and Gore-Tex more practical than fur. But some birds, like the rock ptarmigan, thrive here. To spot one in winter, you need a keen eye for details, a little luck, and to know where to look. The short black tails, dark eyes and bills, and scarlet eye markings on breeding males are the only parts that don’t blend in with the world of white. The birds are often found in same-sex flocks in winter, with the majority of the population inhabiting bare mountain slopes 1,800 to 2,000 metres above sea level. These mountains have helped shape the Slovenian people as well, who have climbed them throughout a long and rich history of alpinism, exploration, and skiing. On the 150 peaks reaching above 2,000 metres in the small country, ski tracks overlap ptarmigan prints. With a surge in ski touring and summer hiking, these harsh but fragile ecosystems are seeing amplified human traffic.

On a cold March afternoon, we are part of that traffic, gliding past the sharp grey-white limestone rocks, dusted with pale-green lichen. While netting, banding, and nest surveys are all more invasive methods of bird monitoring, point counts are the least invasive. Detecting and identifying each bird by sight or sound confirms its presence in an area.

We are lending fresh eyes to friends who have been roaming the snowy Julian Alps for a week surveying ptarmigan in Triglav National Park. Their research is part of a six-year study called VrH Julijcev, meaning Peak of the Julianas, improving the condition of eight target species and four important habitats in the national park by creating quiet areas where human presence will be restricted and nature will be left alone, by tourists and locals alike.

It’s a reminder that even self-propelled and seemingly low-impact outdoor activities still affect wildlife. Perhaps one day Collins Bird Guide will include a page or two about how to move respectfully through the habitats we share with wild birds, so we can continue to see and hear these amazing creatures in our wilderness playgrounds.

Read more Impact stories.