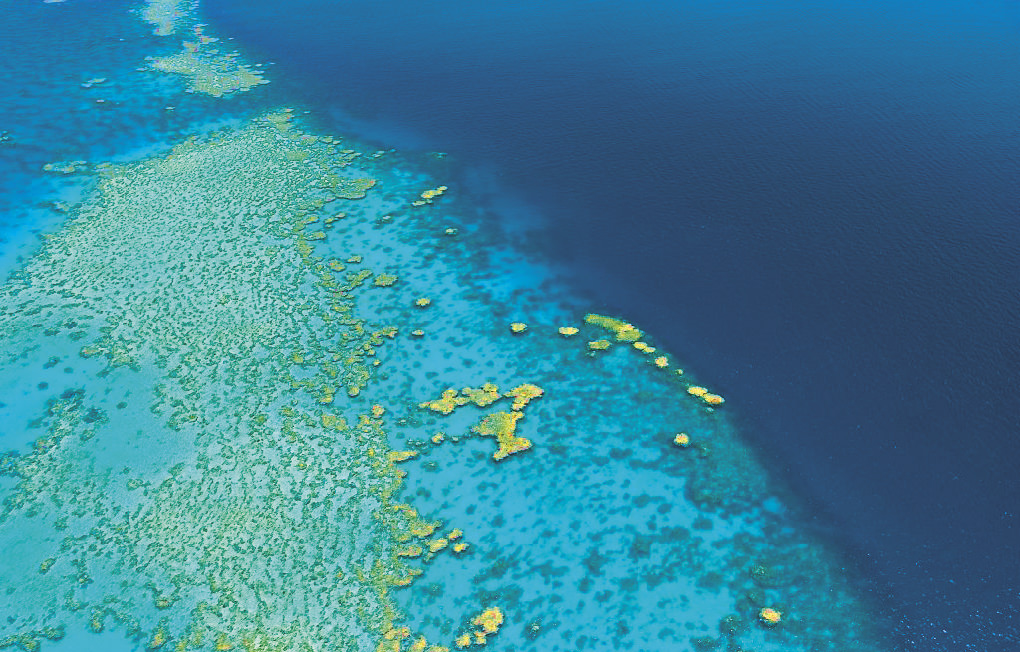

It is one of those places you have to see to really understand. Sun shines down on an aqua blue Pacific that expands as far as the eye can see—but below the water, that’s the real treat. That’s where 2,300 kilometres along the coast of Queensland, Australia make up the iconic Great Barrier Reef—where there are over 30 species of dolphins and whales; 3,000 mollusc varieties; roughly 1,625 kinds of fish; and around 600 types of coral. It is an area so large it can be seen from space.

As is the case with much of the environment today, though, this World Heritage Area is at risk. Acting as its guardian is the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), an Australian federal government agency established in 1975. Through various education, awareness, and on-site protection programs, GBRMPA works to keep the reef as healthy and sustainable as possible. And with an area roughly the same size as Italy, that is no easy feat.

“I liken it to stretching an elastic band: you stretch it, it bounces back; you stretch it more, it bounces back; but if you stretch it too far, it snaps,” says Dr. David Wachenfeld, the agency’s director of reef recovery. “The reef will continue to bounce back from things like bleaching and cyclones, but it won’t do it forever. What we’re doing here is everything we can to improve the resilience of the system.” Still, he says, “we can’t build a bulletproof jacket for the Great Barrier Reef.” What they can do is help it dodge the bullets, and recover from them.

“Probably the cornerstone of our actual protection of the marine park is our zoning plan—it’s a bit like a town planning scheme that says what kind of activities people can conduct in different places,” says Wachenfeld. “The most important element is the no-take areas: people can go in, undertake recreation—snorkel, swim, dive—but they can’t take anything. No shell collecting, no coral collecting, no fishing.” GBRMPA employees also spend time out in the reef, talking to people and making sure they understand what they can and can’t do.

Perhaps the most talked-about hurdle currently facing the reef is mass coral bleaching, which is an effect of climate change. Coral is sensitive, and even a slight increase in water temperature can cause it stress; this makes the tiny zooxanthellae algae that live on the coral and convert sunlight into food for it decide to pick up and leave. The zooxanthellae also give coral its colour, meaning without them, the animal is essentially blank. Mass bleaching occurs when large areas of ocean stay warm for too long, making it hard for the coral to win back its tiny friends. If bleached for an extended time, the coral will die.

And so, GBRMPA’s job seems more crucial than ever before. “I’ve dived in coral reefs and marine environments all over the world,” says Wachenfeld. “And I still think the Great Barrier Reef takes my breath away.”

Read the whole issue in print.