The city of Florence may seem as if it draws all of its beauty from the Renaissance: a living, breathing homage filled with beautiful palazzos framed by orange trees, cathedrals with intricately sculpted domes, and incredible works of art hidden in the courtyards of private homes. But the city has a far more ancient beauty in the form of medieval architecture, much of which has been sadly torn down. One beautiful building that survived from the era, though, is the Palazzo Spini Feroni, which for the last 80 years has been the headquarters of beloved fashion brand Salvatore Ferragamo.

The palazzo provided a stable base from which Ferragamo, named after its founder, turned into a global empire (including a boutique on Vancouver’s coveted Robson Street). The company celebrates its history while also always pushing forward, such as with its new shoe design master’s program in partnership with Florentine fashion school Polimoda.

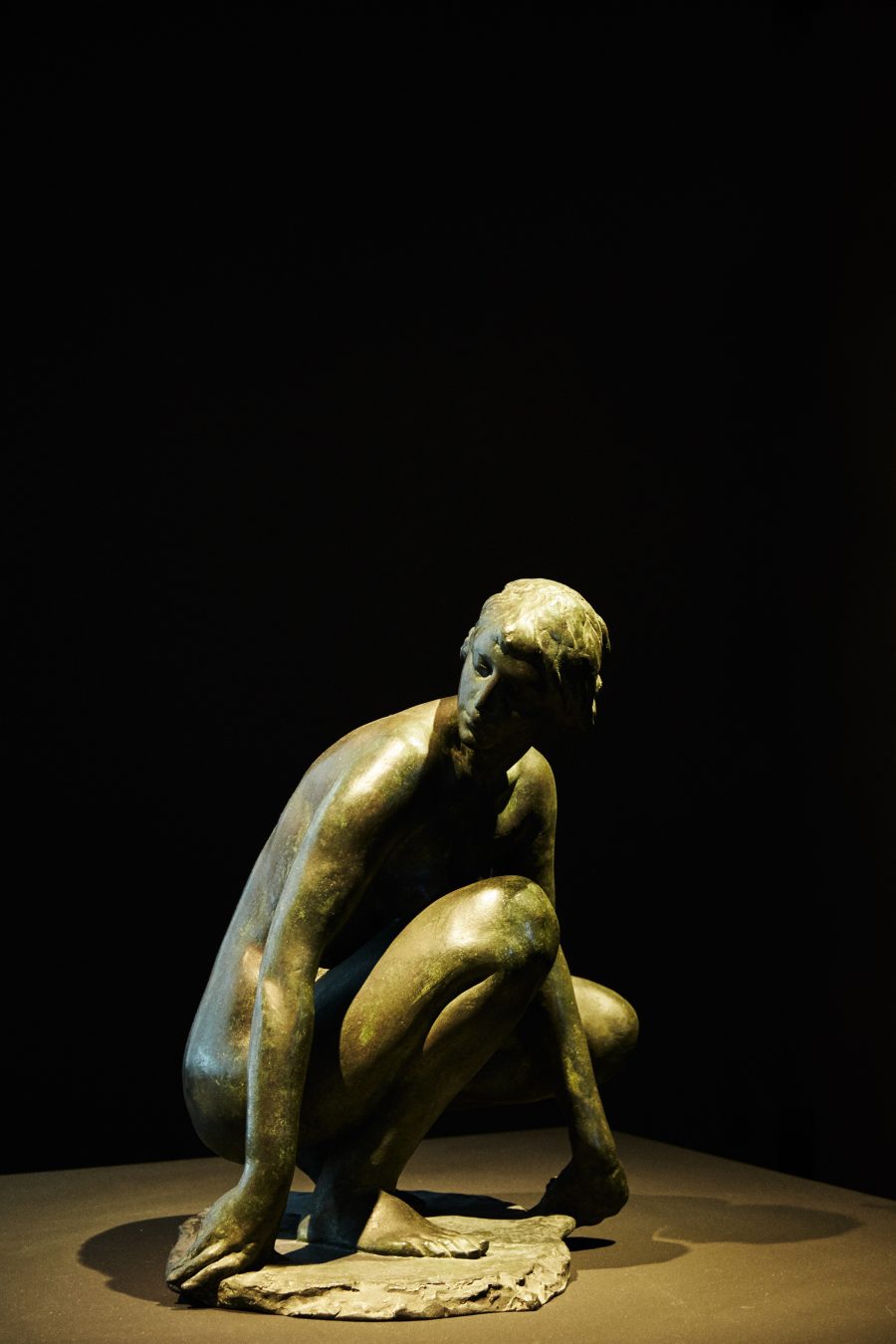

It all began with a passionate aspiring shoe designer from a poor village near Naples who arrived in California in 1915 to make a name for himself, not knowing where he was going to sleep or how he was going to afford to eat. Today, that journey—the visionary’s voyage to America and his relationship with Hollywood—has become part of a fantastic new exhibition at the palazzo’s onsite Museo Salvatore Ferragamo. Walking through the modern glass doors, history is nestled alongside modernity at every turn. The intricate detail of the palace’s architecture is breathtaking in itself, from glossy marble columns to ornate murals covering the walls, but it is also evident how much love and effort has gone into restoring this space.

An exquisitely appointed corridor decorated with art and soft lighting siphons off into rooms filled with glass-encased sketches of Salvatore’s shoe designs. In one space, mounted wooden lasts (which Salvatore used to model his first creations on) sit on a polished table, while long, plush drapes gently press the sun’s glare away. A vast painting by Bernardino Paccetti and Ranieri del Pace covers one side of the wall, the sight of which creates a hushed reverence. There is also a tiny chapel, a place of such beauty and calm that it is easy to imagine the designer himself coming here for quiet reflection under the gaze of stone cherubs.

Salvatore died in 1960 at the age of 62, and it’s a testament to the strength of his intellect that his business is still thriving nearly 60 years later—something his daughter (the second-eldest of six children) Giovanna Gentile Ferragamo, who serves on the brand’s board of directors, is proud to honour and push forward.

When Giovanna enters the room, she is dressed in a soft grey suit and has perfectly coiffed hair. “Oh yes,” she says when asked about her father’s unbridled genius. He was among the first to use cork, nylon fishing line, cellophane, and even straw as materials for his footwear. “Sometimes when you look at the archives you can see there is no material that he did not experiment with when it came to shoes,” Giovanna says. “Sometimes he was forced to find something because a certain leather wasn’t available, or sometimes he wanted to create new things and create some excitement.”

The brand has expanded to include ready-to-wear for women and men, accessories, jewellery, and even fragrance. But always, the heart and soul of Ferragamo lies in footwear—after all, this is where its journey started.

“He had a very fixed idea that he wanted to work with shoes,” Giovanna says. “So he started doing western boots for cowboy films.” The Hollywood exhibition charts that time in Salvatore’s life—between 1914 and 1927—when he turned up in the United States with no money and went on to become a world-famous designer, with Audrey Hepburn as a good friend and Marilyn Monroe as a regular customer. Although Salvatore and Monroe never met, he created the stiletto that gave her that iconic wiggle, and she bought over 40 pairs of his shoes.

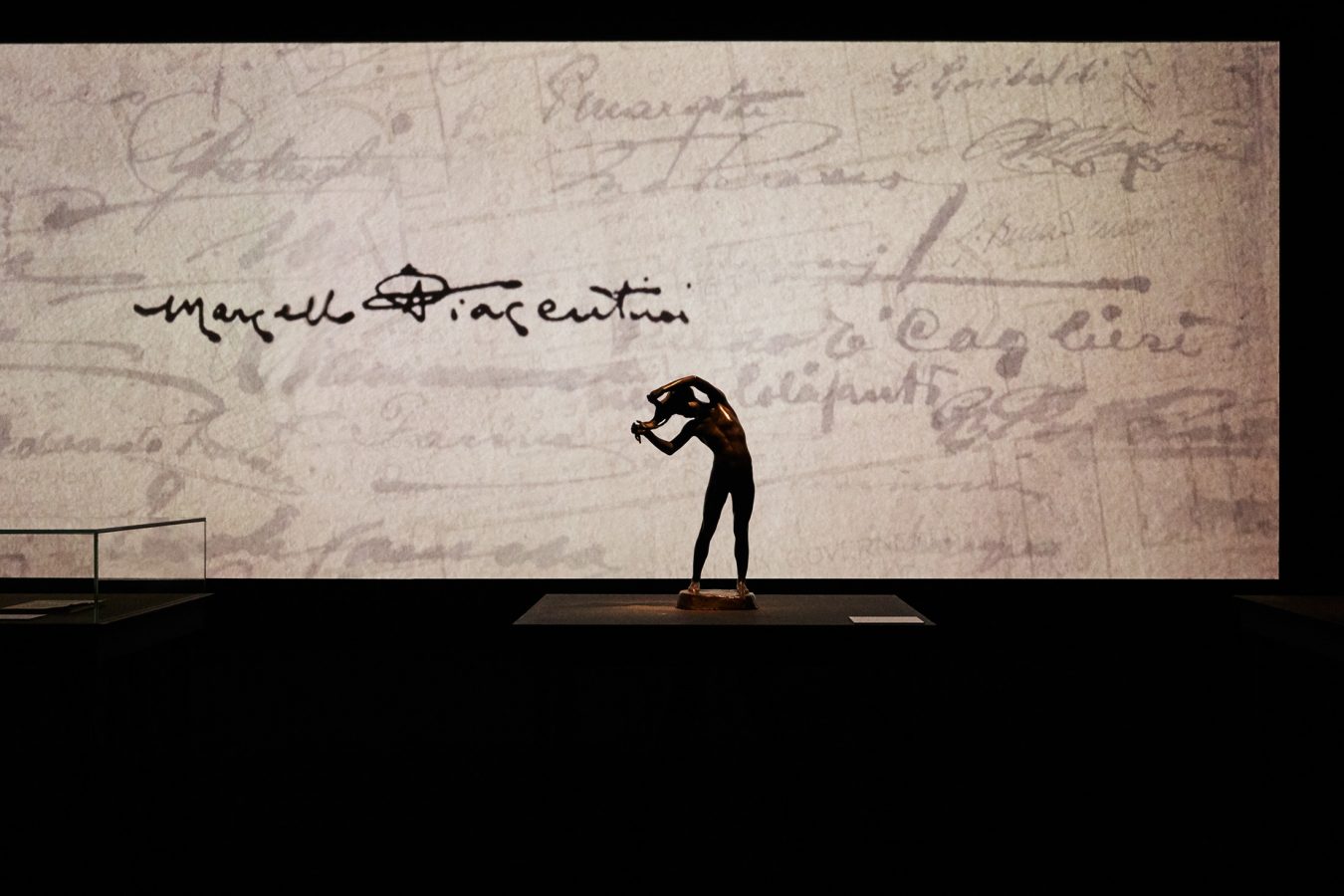

From then on, word of mouth spread and he started working with directors such as the great Cecil B. DeMille and D.W. Griffith. Moving through the exhibition, this part of his career flickers brightly into existence with costumes and accessories that he created for Hollywood’s silent film era. “The world of Ferragamo and movies has always been linked,” Giovanna says. “Videos and films are a form of art. Even the name inside the shoe was designed by a famous contemporary painter at the time,” she adds, referring to the distinctive Ferragamo signature that dons its labels.

It all began with a passionate aspiring shoe designer from a poor village near Naples.

In a bigger sense, the exhibition is a love letter to Italy, says museum curator Stefania Ricci, who has spent a year pulling it all together. Charting Salvatore’s journey right up until he opened his revered Hollywood Boot Shop, the show makes mention of Italian architecture’s impact on California, as well as the Italian actors, such as Rudolph Valentino and Lina Cavalieri, who made it big in Los Angeles. A wall in the exhibition is dedicated to Cavalieri, and as her luminescent face gazes from a photograph, it brings to life the soft beauty of the time.

Salvatore worked with actresses and directors, but he was so focused on and dedicated to his work that he wasn’t swept away by the glamour of it all. Eventually, it was his frustration with the limitations of American manufacturing that prompted his move back to Italy. He realized that to make the shoes he wanted, only Italian craftsmanship would do.

That still remains the north star of the brand. “After my father passed away,” says Giovanna, “all of us one by one joined the company. But our principles were first of all, to have everything manufactured in Italy. It’s not only pride—we really believe that Italy has a craftsmanship tradition for centuries.”

When Salvatore moved back to Italy, his clients followed. “We had a big group of affectionate customers who came back to Italy to see him,” Giovanna recalls fondly. “Florence was wonderful at that time—so many actors, diplomats, the royal family used to come to visit him and order their shoes. It was full of paparazzi.”

When his children were growing up, Salvatore talked to them about his work, and they knew how devoted he was to shoemaking. They also knew how hard he’d had to work to establish himself in Italy, a country that was recovering from the wars. Following his death, though, the family had to make a decision about how they would manufacture shoes going forward. “The handmade shoes were very expensive,” says Giovanna, “and secondly, you didn’t have enough people who were able to produce in big numbers. Also some of the technical operations were much more perfect with a machine.” At present, Ferragamo shoes are partially machine-made, but also handmade, so that every piece has that attention to detail that Salvatore was so famous for.

Even nearly six decades after he died, he is still so revered and loved that people who inherited Ferragamo shoes from their mothers and grandmothers lent them to the family for this exhibition. But what would Salvatore think of it all? The air grows still and hushed as Giovanna reflects for a moment. “Sometimes I think, ‘What could he have achieved if he had lived more?’” she says. “He was such a genius and so ahead of his time. I am sure he would be proud.”

Stay in fashion.