There is a space between different cultures, says Haida artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, “and this space in between is the area where we define difference. It is an unclaimed land and, like a stream between two forests, it is a fertile place filled with refreshment, motion, light, and creativity.” In this story and video from our Autumn 2015 issue, Yahgulanaas shares his commitment to community and his vision of culture as connection, and welcomes us into his home studio.

Born 1954 in Prince Rupert and raised in Haida Gwaii. Direct descendant of Haida artists Isabella and Charles Edenshaw, cousin of master carver and artist Jim Hart. One of his Haida names is Yahladaas, translating into “White Raven.” All of this does very little to describe the creative energy, social consciousness, multicultural visionary that is Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas.

One of his published print works is called Flight of the Hummingbird. It is a parable of sorts, about how a community survives even the most dire challenges by each member taking some measure of responsibility, or, in the words of the hummingbird, “doing what I can.” Yahgulanaas illustrates the book; essays by Nobel Peace Prize winner and founder of the Green Tree movement, Wangari Maathai, and by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, serve as a foundation, revealing some of Yahgulanaas’s core beliefs as a community member and an artist. He served for decades as a leader in his Haida community, and was elected chief councillor of the Old Massett First Nation.

The artist in front of his work, Sei, located near the Vancouver International Airport.

“Everyone in a community needs to contribute some time,” he says. “If all, or most, citizens put in those long hours and rotated through various public offices and we didn’t establish lineages or lifetimes of leadership, we might see a far gentler attitude, less judgment, and far less caustic passions in politics.”

For him, the transition to full-time artist was logical, natural, and necessary. “Knowing I was an artist is of course different than needing to be an artist,” he says. “Knowing was early, far earlier than I can recall. Needing was a choice forced by time. I had spent decades in community service and knew that the artist needed time to be fully realized. I made this decision in the late 1990s.”

He pauses, reflects, before adding: “The departure from over a quarter century of community service was eased by my feelings that the experience of community service helped me understand that art also needed to be in service of others. Art is not a self-service industry.”

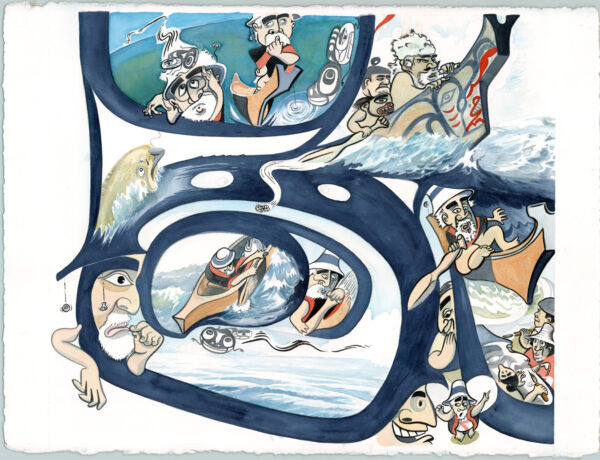

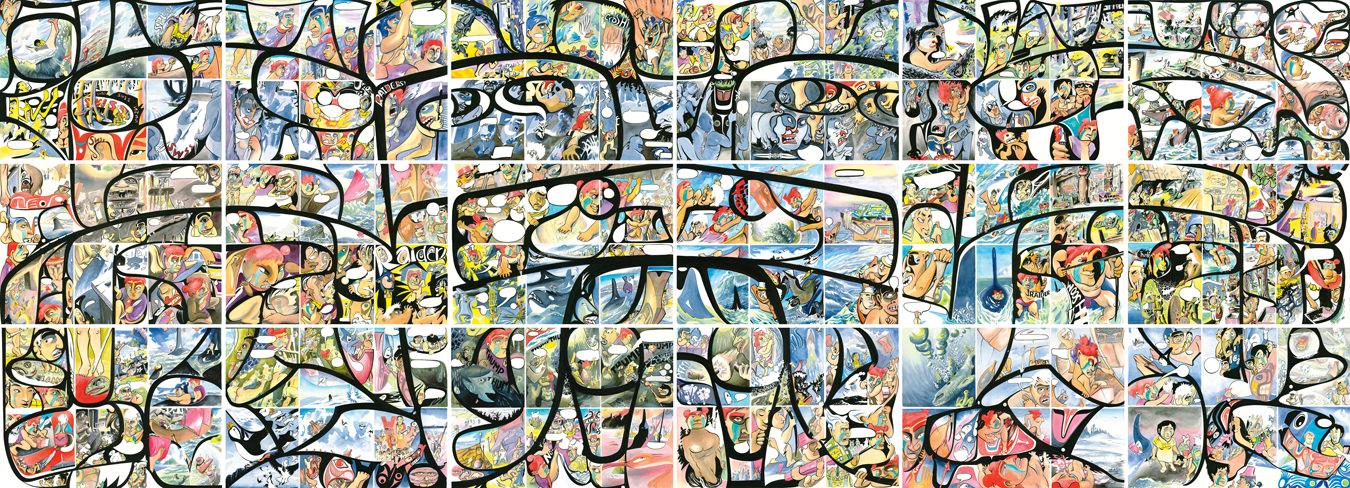

The creation of a five-metre-long mural, unveiled in 2009 and titled RED: A Haida Manga, serves as an over-arching statement of his belief in open-minded cultural exchange; RED was also published as an illustrated book. In both forms, it is keenly illustrative of his overall philosophy, that embracing the adjacent spaces of two cultures can create something unique, fabulous.

RED: A Haida Manga, 2008. Watercolour, ink on paper.

For Yahgulanaas, there are readily identifiable aspects of any culture. But, when dealing with different cultures, “there is space between them, and this space in between is the area where we define difference. It is an unclaimed land and, like a stream between two forests, it is a fertile place filled with refreshment, motion, light, and creativity. It never needs to be a war-torn conflict zone. What this space between two cultures becomes is according to our conscious choice.”

RED is a work deeply influenced by Haida traditions, but it is also inspired by his experiences in Victoria’s Chinatown, where he learned brush techniques from world-renowned Master Choi. “Teacher Choi from Canton taught me that art did not need language,” he says. “That has stayed with me permanently.”

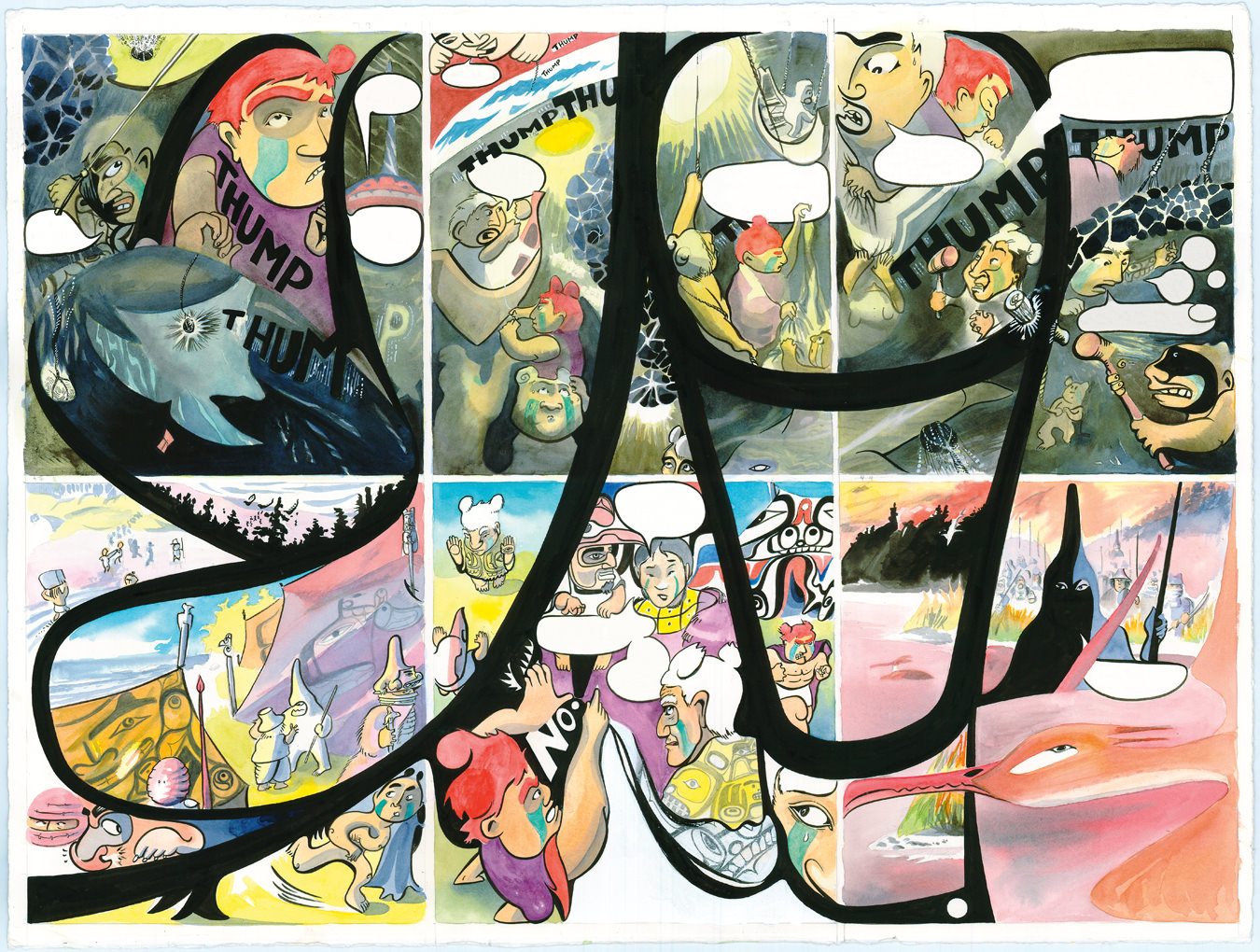

Panel 2 of RED: A Haida Manga.

Yahgulanaas’s work emblemizes different cultures joining, rather than clashing. “In all my various roles, but particularly in community leadership, I was motivated to focus on Indigeneity because here was where the need was greatest. Ours was a community that was still under an assault that Canada had inherited and institutionalized,” he explains. “Apparently my Northern European heritage was doing relatively well without my active assistance. I always knew never to sanctify one and demonize the other. I still understand that I can love and embrace both.”

As if to somehow illustrate his point, Yahgulanaas has worked in a wide array of genres, in a vast collection of mediums and materials, creating large-scale public art installations such as the recently unveiled piece Sei, near the Vancouver International Airport; works in acrylic and in watercolours; pieces using derelict automobile parts. The original RED mural is currently on a multi-year exhibition tour. “Art in all cultures serves as an identity marker, a language, and a connector between its subscribers,” he says. “It is true that art/material culture as object/event within Haida means something substantially different than when that object/event is located outside of Haida.” That is why it is so important for Yahgulanaas to explore that space between.

Naaxin Copper, 2013, car hood, copper leaf, paint.

He is always mindful of art as an active participant in a larger discussion, and always vigilant, even though his work is overwhelmingly playful and positive. “Canada is constructing itself out of many immigrant threads and its relationship to pre-Canadian societies is so fraught with outstanding serious Constitutional irregularities that it would be best to view this young nation state as a process,” says Yahgulanaas. “Art should be a part of that process.” He has drawn inspiration from Haida artists, but he also points to Barbara Hepworth, who is “engaged in piercing through the mass of a thing. Her work resonates with my idea that culture, the species itself, is a mass that needs to have void spaces, openings where redefinition is not only possible but desired and necessary for the health of the entire mass.”

Yahgulanaas is making the most of his time. He is a model of prolificity, and of consistently creative ways to explore his found themes, all of which are borne out of his years as a community builder, with the Gwaii Trust being one of his most clear and tangible legacies. He sees the world clearly, and with joy, but he is completely unique.

“Light and sound travel in waves. Perhaps the principles that govern the distance between our eyes and a painted canvas or your ears and a jazz musician are the same principles that apply to the collision of galaxies,” he says. “The stroke of a brush pulling across the paper must then adhere to the same principles that govern a mote of dust in deepest space. It is our human lens that makes the everything look human, when really it is the human that looks so much like the everything.”

As he makes his way back to a ferry that will transport him home, he signs a copy of RED, actually altering a few of the panels, adding a flourish or an accent here and there. Watching his hand and the brush fly across paper, applying ink as precisely as a hummingbird visits a flower, it becomes apparent how rooted in physical reality is his vision, which in the end is his greatest strength.

This article and video from our archives was originally published with our Autumn 2015 issue. Read more about local artists, and check out Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas’s original artwork for our Autumn 2019 issue.