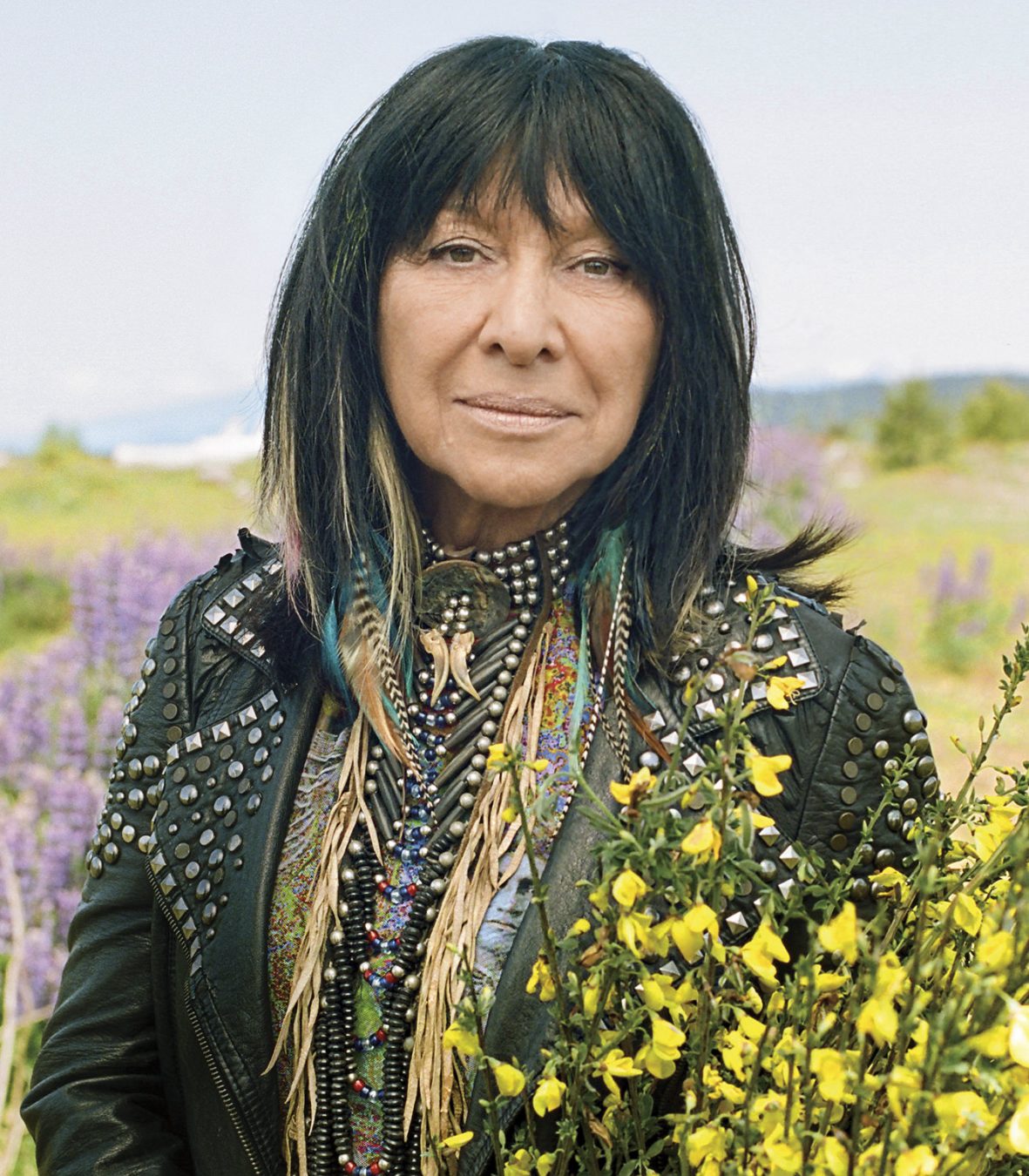

While this year’s crop of Rock And Roll Hall of Fame nominees for induction is the most diverse it’s ever seen, and women are finally, nearly equally represented in the list of 16 hopefuls, the change is long overdue—and the voters have yet to actually cast their ballots (deadline is April 30). As of January 2020, women still made up less than eight per cent of the Hall’s inductees, and as of today Buffy Sainte-Marie, who just celebrated her 80th birthday, has yet to be nominated (though Whitney Houston finally cracked the glass ceiling last year). In this essay from our Autumn 2018 issue, music journalist Andrea Warner reflects on the women whose stories deserve to be honoured and told.

I remember the first time I ever heard Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s music. Though I can’t recall the exact online article I was reading, I’m pretty sure it was talking about the untold stories of female music pioneers of the 20th century. When I pressed play on the accompanying video, which was taken sometime in the 1940s or ’50s, I saw her: a gorgeous, vibrant African-American woman taking to a stage in what looked like a train station. She opened her mouth and her voice belted out into my headphones. I was swallowed whole.

When Tharpe got to her guitar solo, I felt like my head and my heart were going to explode. She was incredible—fearless and frenzied, but fully in control and such a dynamic entertainer. It was love, and it was unforgettable.

Tharpe was one of the blues and gospel greats, and she’s credited as the godmother of rock and roll. After all, this was a woman who absolutely shredded her guitar throughout the ’30s and ’40s. And yet, until April 2018, she was notably absent from the very music industry landmark that might never have existed without her: the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

In 1986, the Hall of Fame voted in its first class of musical acts and artists. There were 16 inductees in total—all male—many of whom were influenced and inspired by Tharpe and whose fame eclipsed hers. Thirty-two years later, women only account for about 15 per cent of the more than 300 musicians who have been celebrated in the iconic Cleveland museum.

Based on those numbers, the story of rock and roll would seem to belong to men. But that’s simply not the case.

I’ve always been interested in women’s narratives, and in helping give female artists the credit they deserve. That was one of my motivations in wanting to write Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography (Greystone Books, September 2018). Sainte-Marie is an Indigenous musician and activist, and while she is known for her jaw-dropping 1964 debut It’s My Way!, her larger contributions to rock and roll have been widely underappreciated. During one of our many interviews, she told me she is actually surprised when she receives any recognition. Her comment made us laugh in a way that said we knew there was a bigger picture beyond the frame.

Sainte-Marie was born in Piapot, Saskatchewan and has since made her home in both Canada and the United States (these days, she has a farm in Hawaii that she adores). She’s a folk music icon and was hugely influential in the ’60s protest movement, but she is also wildly contemporary and relevant. At 77 years of age, she is still putting out ground-breaking new songs today, and continues to tour and perform frequently—including at the recent inaugural Skookum Festival in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

She’s considered a pioneer of electronic music; she co-produces her records; she won an Academy Award for best original song (“Up Where We Belong” from 1982’s An Officer and a Gentleman) and has also composed for film; she has had her music blacklisted by two American administrations; and she was the first person to use a powwow sample in a song (“Starwalker,” off the album Sweet America, in 1976).

She has also written countless classic songs that have been covered by everybody from Elvis Presley to Bobby Darin to Donovan. All three of these men have been inducted into the Hall of Fame, and all three scored huge hits with Sainte-Marie’s songs—something she never experienced for herself.

Presley and Darin took her 1965 feminist pop standard, “Until It’s Time for You to Go,” and gender-flipped it into an epic ballad. In 1965, Donovan covered her powerful 1964 peace anthem, “Universal Soldier,” and made it a smash. To this day, there are people who still believe Donovan wrote the track himself. He also covered Sainte-Marie’s 1964 song, “Cod’ine,” which Janis Joplin adapted as well and turned into a hit. (Joplin, it should be noted, is one of the few females who has been included in the Hall of Fame.)

I consider Sainte-Marie to be among Canada’s four most iconic artists—the other three being Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, and Leonard Cohen—but of that peer group, she is the only one not part of the Hall of Fame. She has never even been nominated.

Someone equally deserving who did get inducted in 2018 is the late Nina Simone. An exasperated “Finally!” could be heard around the internet when the news was announced, along with a flurry of fingers typing about how long overdue her inclusion was and unpacking some of the barriers that kept the incomparable vocalist, songwriter, and activist—who died in 2003 at the age of 70—from receiving the honour sooner.

Simone was known as the high priestess of soul, and whether I’m listening to her recordings or watching archival footage of her performing—well, both are transfixing, mesmerizing experiences. Simone’s powerful contralto burns with intensity, an inferno of feeling bursting free from her body. She was a master of passionate, provocative, reckless authority, refusing to brace for impact whether she was commanding her piano or the mic stand. Her music bridged and boldly redefined genres, eradicating barriers between soul, classical, jazz, R&B, gospel, folk, blues, and pop, and her legacy continues to impact countless present-day artists.

More than three decades went by without the Hall of Fame properly honouring Tharpe’s or Simone’s legacies. Sainte-Marie is still waiting, as are thousands of other influential women, and especially women of colour: Ella Fitzgerald, Whitney Houston, and Queen Latifah, to name a few. What makes these omissions all the more glaring is the fact that 22 artists hold the distinction of having been inducted twice—and all of them are men. Eric Clapton has actually been initiated three times.

When women, particularly racialized women, are relegated to the margins and the footnotes, their contributions are minimized and invalidated. Awarding organizations like the Hall of Fame are perpetuating the closed-minded belief that influential musicians are men, and that women musicians are extraordinary exceptions to their usual roles: muses and groupies, backup singers and bass players, cultivators and supporters and enablers of artistic genius but never the sources of it. I don’t want to care about the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, but I can’t help it. Whether I like it or not, it is recognized around the world as an important marker of musical greatness. The problem is that it is missing so many greats.

All my life, people have waxed on about the likes of Bob Dylan and the Beatles and Elvis—and they are undeniably great, but their mythologies take up all the space. I’ve always wondered about the stories I wasn’t being told. Stories about women who, like Simone, Tharpe, and Sainte-Marie, didn’t just shatter glass ceilings, but were forced to build new worlds in order to thrive. Women who were doing the work for just a fraction of the recognition and success, and whose contributions matter, perhaps today more than ever.

This essay from our archives was originally published in our Autumn 2018 issue. Read more personal essays.