There’s no mistaking Eric Ripert. The 56-year-old French-born chef’s shock of steel grey hair and generous smile is familiar to anyone with an interest in serious cookery. Those of us not fortunate enough to have visited his New York restaurant Le Bernardin will recognize him from his television shows (Avec Eric, On the Table With Eric Ripert), his cookbooks, or as a close friend of the late chef, broadcaster, and writer Anthony Bourdain.

He is known for his masterful fish cookery—the menu at Le Bernardin is a love letter to the sea: peekytoe crab, Dover sole, “barely cooked” Faroe Islands salmon, striped bass, yellowfin tuna. Prepared as tartare, poached, baked, or pan-roasted, and garnished with the flavours of Europe (black truffle barigoule, squid ink fideos, chorizo emulsion) or Asia (yuzu rice, ginger-wasabi emulsion, dashi), Ripert’s dishes practically swim off the page into your senses.

“I’m not a vegetarian or a vegan. I eat meat, and I eat fish, eggs, and dairy, but I want to inspire people to cook and eat more vegetables.”

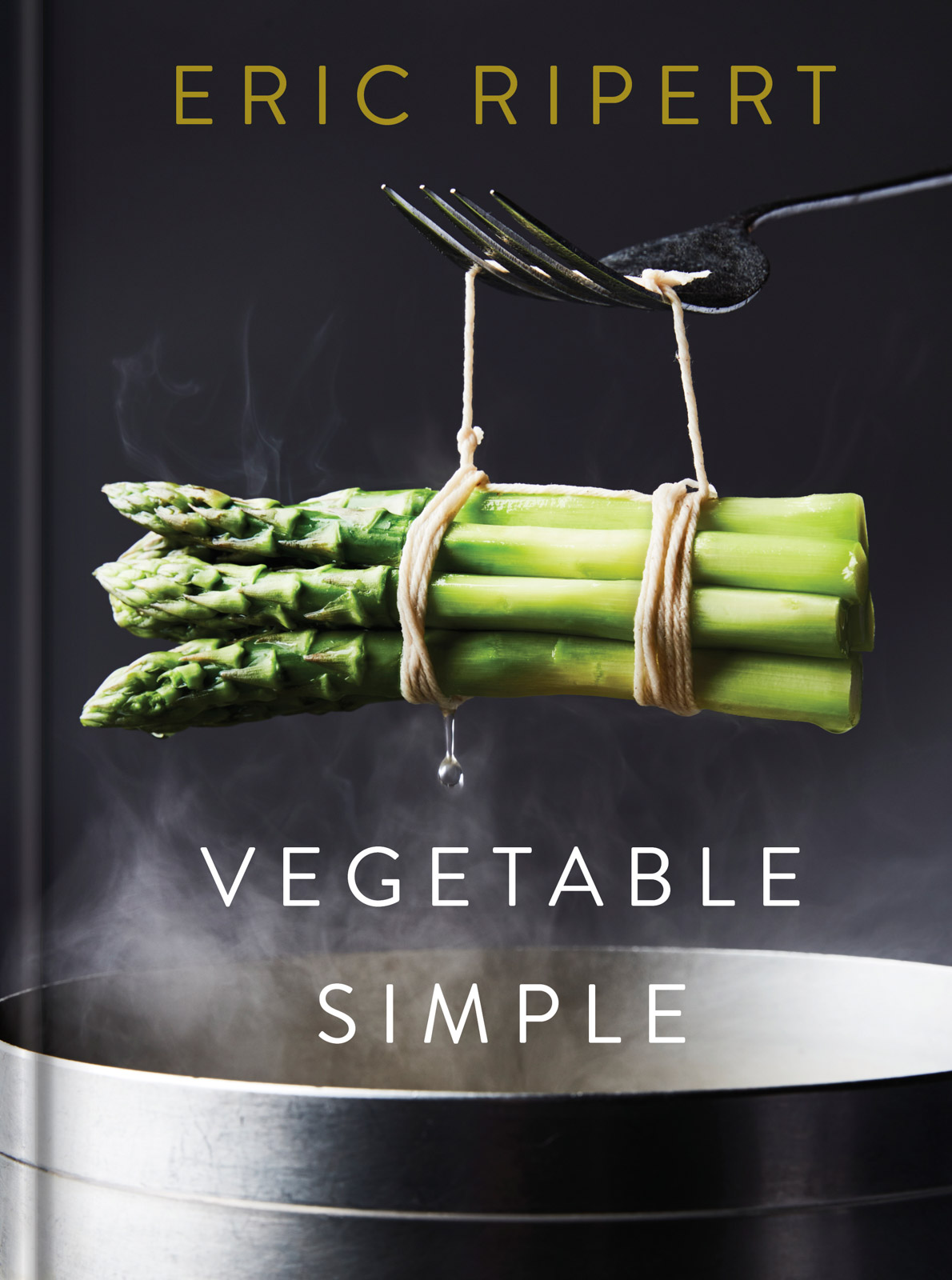

We meet over FaceTime from his New York apartment. He’s wearing a plain grey T-shirt and, on his wrist, a mala prayer bead bracelet—Ripert has been a practising Buddhist for more than two decades. We’re here to talk about his latest project: a new cookbook to be released in April, Vegetable Simple, focusing on, yes, vegetables, prepared simply. Its pages burst with beautiful varieties shown off at their best (photographs are by New York celebrity portraitist and Ripert friend Nigel Parry). There are soups and salads, pastas and sides, all of which Ripert hopes will encourage readers to set plentiful tables of healthy and delicious dishes. Some are basic (a tomato with salt, pepper, and olive oil), some outrageously indulgent (black truffle quesadilla, anyone?), but the common thread is Ripert’s passion for produce—and how to return from the market with the best of what’s on offer.

It is, Ripert says, how he loves to cook at home. “I wanted to do a book of vegetables because, when I invite friends to my house, I love to cook dishes inspired by my life and my travelling and so on, and what’s seasonal,” he explains. “I make a selection of vegetable dishes and put them in the middle of the table, and people can help themselves. It’s very convivial.

“Vegetables are very different from each other,” he adds, with a smile. “Asparagus is different from potatoes, which are different from tomatoes—so I think you have the benefit of having many different flavours and textures.”

When he talks about shopping for vegetables, his face lights up. “The smell,” he rhapsodizes. “Especially when you go to the farmers market. I love it.”

The problem, he says, is that people still see vegetables as an afterthought due to, he suggests, too many childhood exhortations to finish them. “It leaves people with the idea that the reason to eat is the roast chicken on your plate, not the beautiful artichokes or fresh English peas.

“But really, vegetables have a lot of personality. It’s just you have to know how to prepare them, and the book is here to demystify not only how to cook vegetables the proper way but how to shop and store them. It’s not complicated; you just need someone to guide you.”

Writing the cookbook has, he says, been “pure pleasure,” giving him space to draw on his own philosophical perspective. “I’m not a vegetarian or a vegan,” he notes. “I eat meat, and I eat fish, eggs, and dairy, but I want to inspire people to cook and eat more vegetables. It’s healthy, good for the planet, good for the animals—it’s really a win-win.”

Ripert adds a dedication in the final pages that, he says, is where the real inspiration lies. “Lastly,” he writes, “I would like to thank Matthieu Ricard, who, through his book A Plea for the Animals, planted the seed that ultimately led me to create Vegetable Simple.”

Born in France, Ricard is a Buddhist monk with a PhD in cell genetics. “He has a very interesting story,” Ripert says. “His father was a famous French writer and philosopher of the 20th century—Jean-François Revel—and Ricard was a scientist at the Pasteur Institute. One day he decided to check out and become a monk, went to live in Nepal, and became the French translator of the Dalai Lama. He has a brilliant mind and has written many, many books. When I read A Plea for the Animals, I was like, ‘whew, breathe.’ And so, I give him thanks.”

It goes without saying that this has been a tough year for Ripert. New York City was one of the pandemic’s first hot spots, which has taken a toll on residents and businesses alike. Along with many of his peers in the city, Ripert joined philanthropic powerhouse José Andrés to feed those in need through the Spanish chef’s nonprofit, World Central Kitchen. “The city was in disarray,” he sighs. “But with the support of José and also City Harvest—a food rescue organization I am involved with—we were able to do 400 meals a day from May to November. It was good.”

His commitment to Buddhism, he says, has helped him “very much. It is a very challenging time, and daily practice is definitely helpful. But my practice is also very challenging.” He adds, “It’s not like, because I am a Buddhist, I’m totally Zen 24/7. I still struggle, I still stress. By repetition, the practice basically changes your personality, and if you were someone with a lot of stress or anger or fear, the practice transforms you in many ways. But it’s a lengthy process.

“When you have a big challenge like COVID, sometimes the practice is a challenge, and whatever you thought you were able to tackle, it’s more difficult. Sometimes, if I’m in the middle of a very stressful situation, I forget about the principles of Buddhism for a little bit, and then I come back to them and find my way.”

When we spoke in February Ripert was looking forward to reopening Le Bernardin as soon as New York City allowed indoor dining again, but at press time the restaurant was set to reopen March 17. Desperate to get his business up and running again, Ripert assiduously implemented safety protocols for the first reopening in September (Governor Cuomo shut down indoor dining in March 2020, and again in December) and even installed in the dining room and kitchen a state-of-the-art heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning system more commonly found in hospitals and airports. “It bombards the air with ions that kill the virus,” he explains.

“When we were open, we took whatever safety measure we could,” he shrugs. “And we are going to reopen at whatever capacity they allow. Even if we lose a bit of money, it’s better like that—better than closed. Being closed is a disaster.

“Whoever can survive 2021 will be okay in 2022,” he suggests. “But I think we are going to lose a lot of restaurants this year.”

Eric Ripert’s Vegetable Pistou

My aunt Monique would make this every year in the middle of August. While it’s a simple dish, it’s a true homage to vegetables and became such an occasion in my family that my cousins and I would get excited when my aunt would start making it. Our whole family would gather at long tables in the garden on those warm August evenings in Provence to eat this pistou together. Don’t be intimated by the number of ingredients. The recipe is lengthy, but the bulk of the work is prepping and cutting the vegetables, which you can start a day in advance.

Ingredients

½ cup dried small white beans (navy beans)

Fine sea salt and freshly ground white pepper

¼ small onion, cut into ¼-inch dice

1 medium carrot, cut into ¼-inch dice

½ medium zucchini, cut into ¼-inch dice

12 to 15 green beans, ends trimmed, cut into ¼-inch dice

1 medium tomato, peeled, seeded, and cut into ¼-inch dice

3 cups loosely packed fresh basil leaves (about 1 large bunch)

1 garlic clove, coarsely chopped

⅓ cup extra-virgin olive oil

Method

Place the beans in a bowl, add water to cover by 1 inch, and refrigerate overnight.

Drain the beans and transfer them to a medium pot. Add 3 cups of water and bring to a simmer. Cook at a simmer until the beans are very tender, about 1 hour. Once the beans are almost cooked, season them with salt and white pepper, then stir in the onion, carrot, zucchini, green beans, and tomato and cook for 10 to 12 minutes.

Meanwhile, bring a pot of lightly salted water to a boil. Set up a bowl of ice and water nearby. Blanch the basil in the boiling water for 30 seconds, then drain and quickly transfer to the ice bath. When cool, gently squeeze out the excess water and transfer to a blender. Add the garlic and with the blender on low speed, slowly stream in the oil. Puree the pesto and season with salt and white pepper.

Stir the pesto into the beans and vegetables, then taste and adjust the seasoning if necessary. Divide the pistou among four warmed bowls and serve hot.

Eric Ripert’s new cookbook, Vegetable Simple, published by Penguin Random House, was released April 20, 2021. The recipe for Vegetable Pistou is reproduced with permission from the publisher. This story is from our Spring 2021 issue. Read more Food and Drink stories.